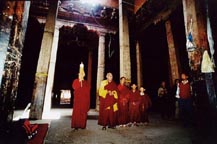

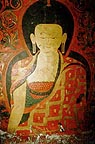

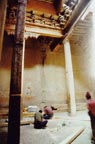

A New Ceiling for the Roof of the World January 20, 2000 The top floor room of the Sakya monastery in Boudhanath resonated with the muffled sound of drums and horns from the assembly hall, three floors below. John Sanday, a world-renowned expert in the conservation of ancient monuments, kneeled to present a kata offering scarf to The Venerable Tri Rimpoche, the 79 year-old leader of Nepal's Sakya sect of Tibetan Buddhists. Rimpoche smiled and motioned John to remain kneeling while be draped the kata around the neck of his offerer -- as a blessing in return. Then, reaching beneath his colorful sitting carpet, Rimpoche withdrew 200 rupees and tucked it into John's pocket, saying "this is for tea, on your important journey to Mustang." Sanday and his team of restoration specialists and carpenters were understandably anxious. They were embarking on a complicated and daunting mission to stabilize and restore an ailing 15th century monastery, damaged by weather and warped from age and infirmity. The Thubchen Gompa, dedicated to Sakyamuni, Buddha of The Present, is located within the walled city of Lo Manthang, the capital of the formerly forbidden Kingdom of Mustang, a cultural relic of Tibet near the Nepal-Tibet border. The hardest part would be getting the permits for all of this to happen. Bureaucratic momentum doesn’t readily allow a waiver of the $700 fee that allows tourists to visit upper Mustang for only 10 days. Just as unnerving was Nepal's continual re-shuffling of government officials -- the ripple effect of an earlier "change in government." One of the first experts on Sanday's team to visit Thubchen was Jaroslav Poncar, a Yugoslav physics professor who emigrated to Germany 25 years ago. "Jaro" has melded his passion for photography into both art and science. Alchi, Ladakh's Hidden Buddhist Sanctuary, his stunning book on the art of this ancient monument, is a rare volume, Promethean in both size and detail. I felt fortunate to join Jaro and Sanday as a representative of the American Himalayan Foundation, the sponsor for this project. At present, Jaro is the principal photographer for the Apsara Project, a complete photographic documentation of the monuments of Angkor Wat. I asked him about archiving the images he shoots. Rather than praising the longevity of digital media, Jaro prefers to store shots of traditional monuments on photographic film. "To archive images for inventories, we shoot them with a digital camera and then print them onto film, using an'exposer.' The resulting film is easily recognizable, and free of the compatibility questions presented by the unknown future of computer hardware and software." Jaro's job at Thubchen was to carefully photograph the architecture and wall paintings in their present condition, with special attention to damaged areas. By lighting some of the walls almost directly from the side, he could even illustrate the surface texture. The occasional need to work in complete darkness (for better control of flash exposures, in which he clicks off 20 or more flashes while the shutter is open) presented unusual challenges. The assistants that he trained locally caught on quickly. On July 16, the Khempo (the respected religious leader of Mustang's Choede Gompa), John Sanday, Judda Gurung (Director of the Upper Mustang office of the Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP)) and I gathered with several Lo Manthang leaders at the palace of Jigme Palbar Bista, the Raja of Mustang, the 25th in Mustang's lineage of hereditary kings. This preliminary meeting would set the groundwork for the town meeting the next day. It was agreed that a committee should be formed to decide all issues that might arise, and to appoint an observer who would be present at all times during work in Thubchen Gompa. Shortly after dawn of July 17, Lo Manthang's town crier stood on a high -rooftop and called all residents to a meeting in the courtyard of the Jampa Lhakhang (the Chapel of Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future), one of Lo Manthang's two other ancient buildings, built in 1450, 20 years before Thubchen Gompa. Two hours after the designated time -- the usual delay for town meetings -- a quorum of villagers gathered. The Khempo had returned from Tibet to discuss the Thubchen renovation, and he stood and addressed the crowd of more than 120. "I am pleased at the auspicious intersection here of donors, architects, restoration specialists and carpenters. We are grateful for your motivation and your energy and skill, and for the craftsman you have brought to join ours. As for the towns-people, because we are doing this work for dharma, for religious merit -- as well as for the benefit of the community - we must not make any exchange of our services or goods with a motivation of profit." The mole squarely in the lower middle of the Khempo's forehead, the location of the third eye, the wisdom eye, seemed to radiate the piercing compassion of his other two. "For us, it is though you are bringing light to a dark room, or delivering sight to the blind. And we are especially appreciative to the American Himalayan Foundation for their generous and well-considered assistance." Sanday, his gangly British frame topped by a hat pinned up on one side, towered above the Lobas seated on mats in the courtyard. "It is a great privilege to be able to work here, and we hope this is the beginning of a long relationship highlighted by the training of Lobas and the revival of local traditions. In fact, we are totally dependent on your expertise and your enthusiasm, for this is really your project." The townspeople agreed to provide clay for the roof reconstruction, labor at prevailing rates, and to help inventory the features of the structure, monitor the project, and hold regular meetings. ACAP would provide the needed timbers, and provide oversight and support, as needed. Indra Bista, Vice-Chair of the Village Development Committee, made a short speech reiterating John's and the Khempo's pleas for local participation. Moments later, the townspeople disbanded, only to regroup in five large huddles in the corners and center of the courtyard, each composed of residents of Lo Manthang's five wards. Democracy in action. 10 minutes later, each Ward Chairman stepped forward and announced the names of their appointees to the Thubchen Gompa Restoration Committee -- in most cases the Chairmen themselves. The ACAP office accountant recorded the minutes of the meeting, which were read aloud by Indra Bista, then circulated for signatures and thumb prints. WOOD FROM TIBET The question of where and how ACAP would get the 66 roof beams - each 18 feet long and close to 260 pounds - -was nearly answered when the owner of Cosmic Air, Capt. Pradhan, Nepal's first helicopter pilot, offered five Mi-17 chopper charters at a reduced price. He would airlift the timber directly from the forest, -via helicopter logging, in exchange for wood that he needed from ACAP for his 5 star hotel with heated swimming pool, now under construction near Jomsom. ACAP was already embroiled in a controversy over commercial use of Mustang villagers' timber, and decided to shift their wood search to Tibet. Large timbers from Tibet, however, must be transported on a specialized truck (the long pieces would collapse the cab of a standard truck) over 1,000 kilometers from Kongpo, far to the northeast of Bhutan. Also, they would have to be off-loaded and re-loaded for some of the river crossings. But because ACAP's Judda Gurung could not enter Tibet to purchase the wood (the Chinese allow only Lobas to cross at the border, for temporary purposes), a Loba would have to go Town leaders and ACAP were convinced that only the Raja had the clout needed the pull off such a purchase. The Raja volunteered to ride his horse well into Tibet to personally negotiate the deal -- despite his anxiousness to join the Rani, the Queen, who was undergoing medical treatment in Kathmandu. Fortunately, the Tibetan wood dealer was at the border that day, instead of at the county seat 3 days away, and the Raja quickly scored the deal. Each piece would cost over $150, and delivery would take 4 to 6 weeks. Just In Time Inventory. As he rode back to Lo Manthang that afternoon, the Raja (respectfully addressed as "Kundun" by the people of Lo) was clearly proud of the prompt settlement. He leaned from his horse and to waiting Lobas, hats in their hands, passed out handfuls of White Rabbit candies brought from the trading post just inside Tibet. He had also returned in time to catch a return seat on Sanday's helicopter charter, which arrived the next morning loaded with plywood and building supplies, The 66 beams would be sufficient only for joists at the west end of the hall -- a seemingly inconsequential addition to the network of beams, joists, capitals and corbels that formed the complicated ceiling, which is supported by 42 pillars over 20 feet high. The magnitude of the task completed 550 years earlier in this remote, treeless province could now be well appreciated. Before work could begin, the gompa and the sacred energy within would have to be protected from defilement by the workers. On the morning of the l7th, the Khempo and four monks performed the Aartsok ceremony, in which he collected the "Wisdom Beings" from the wall paintings and statues, and transferred them into a melung, a mirror fashioned from a brass disk on a staff. The Khempo wrapped the mirror in a kata scarf, and tied It to a column near the altar. The Wisdom Beings are now tightly locked within the mirror for the duration of the work, and it is to this that Lobas now make their prostrations and prayers. When the restoration is complete, the melung will be unwrapped and a similar ritual will be engaged to re-transfer the Wisdom Beings to the paintings and statues. Until that time, the Khempo has asked that no one move the brass mirror or the column to which it is attached. Most of the monks did not attend the ceremony because, The Khempo said, they would likely have walked on and crushed insects in transit to the assembly hall. But the 30 monks of Choede gompa were not idle. They performed a day-long 21 Tara puja, including obstacle removal, blessings and purification for the workers and the buildings. For the final consecration, the Khempo climbed to Thubchen's roof and recited prayers of protection in the four cardinal directions. He then dipped the lip of a Tibetan antelope horn in blessed, clarified butter, and scored lines across the roof's dry clay surface -- to propitiate the lu, the pre-Buddhist serpent spirits residing within the earth that may be disturbed whenever new earth is broken. To inaugurate the work itself, two young men with both parents living were selected, and they began digging in locations on the roof that the Khempo specified. DOWN TO WORK The Sakyamuni Buddha, the central 9 foot tall statue, is made of repousse copper, While inspecting its condition -- not bad for 550 years old -- a monk noticed that some ancient tsa-tsa, clay votive offerings with flecks of gold in them, were spilling from a lesion in its copper back. Along with them were sung paper scrolls, placed inside the statues at the chakra points and near the eyes and ears to vitalize the deity. These, too, had spilled out next to a pile of 11 thangka scroll paintings, likely placed there when activities in the temple went into a dormant phase, centuries ago. The painting of these thangkas may have been commissioned by earlier rajas, for blessings and a long life, and to effect favorable reincarnations for the dead. They were blackened by the soot of centuries of butter lamps, but are likely restorable. The Sakyamuni is flanked by three large statues, Avalokitesvara (Chenrezig), Manjushri, and Guru Rimpoche (Padma Sambhava), positioned on a platform about 8 feet above the floor. The roof directly over them had begun to sag, and a ceiling beam had reached within two inches of the topknot of "hair" On Sakyamuni's copper head. In order to protect these deities during replacement of the roof, durable plywood boxes would have to be constructed. Alongside Loba master carpenters, Newar restoration carpenters from Kathmandu went to work, some using electrical tools powered by a generator kept outside the gompa. Loba townspeople wandered through the gompa as if viewing it for the first time. Hands clasped behind their backs, they stared in wonder at the wall paintings and craned their necks at the ornately carved capitals. Like curious tourists, they asked strings of questions about what would happen next. DISTRACTIONS -- THEN THE ITALIANS ARRIVE On the 15th of August, Sanday's permit to stay in Lo Manthang expired. He was called to see the Chief District Officer in Jomsom, a three day walk. The CDO allowed him to return to Lo Manthang --just as the rains began. The dirt "streets" of Lo Manthang (which also serve as a passageway for hundreds of livestock in the mornings and evenings) turned to a morass of tenacious mud. The pipe carrying the town's drinking water also washed out, and villagers had to carry urns and jerrycans of it on their backs from 4 kilometers away. Then word floated down from Tibet: the 60 pieces of wood beams would not arrive for another two to four weeks due to the flooding of roads across Tibet. On the Tibetan plateau, 1998 was the rainiest monsoon season in memory. Rudolfo Luian and Vincenzo Centani, know collectively as "the Italians" (Rudolfo is Guatemalan, but has lived in Rome for 30 years), brought a half century of experience between them to sites ranging from Cambodia to Yemen to the United States -- where skills such as theirs are difficult to find. Rudolfo set up shop on the south wall doing "Injections", in which a mudclay compound (sifted through a 200-mesh screen) is squeezed behind paintings that had become detached from the wall. Some paintings were found hanging like curtains. Paintings on the bottom half of the south wall are largely missing, due to "rising damp", moisture from the floor and the six feet of earth debris piled outside the south wall. To clean the wall paintings, Lujan and Centani selected a sample area, removed the dust, then dry cleaned it with sponges, effectively lifting off remaining surface dirt. The difficult part was removing a resin layer, similar to a varnish. But by meticulously testing and then working over a patch of wall paintings with a variety of chemicals, their cleaning slowly revealed the remarkable brilliance of the paintings beneath -- as if drawing back a curtain. Sanday was as amazed as the Lobas by the cleaning, especially in combination with a bit of auxiliary lighting. "Suddenly, out of the dark corners you have these wonderful eyes peering down on you." "In Italy and also throughout Asia," Rudolfo said, "people ask us what we're going to do about the missing sections of painting. But here, those who came to watch simply rejoiced in the work they could see." The permit process in Kathmandu had eaten up half the Itallans' time in Lo Manthang, and they had to leave after only two weeks of effort, barely enough to get the work started. It was enough, though, to give the Lobas an appreciation for what was possible. One town leader remarked that for other religious monuments of Mustang, they will now consider restoration in preference to re-painting, where possible. Across the Himalaya, darkened but reparable wall paintings are often painted over -- as was commonly done every century or so. The Italians said they have never seen uninitiated trainees as dedicated and careful as the Lobas who volunteered to work with them. When they left, townspeople piled kata blessing scarves on them nearly above their ears. Two or three more years of summertime work remains. MORE CARPENTRY WORK The restoration work has not been free of incidents. John and the Newar restoration carpenters sometimes present unusual ideas and techniques, and resentment had been growing among the Loba carpenters, who are technically capable of building a structure such as Thubchen themselves. Independent of each other, the Newars and Lobas went on strike. Why bring workers from the outside, when there are competent carpenters at the site? Partly because conserving an old building is technically and logistically more difficult than constructing a new one. Thubchen had become warped and out of alignment due to age and weathering and shifting roof loads, presenting unusual "Chinese puzzle" engineering problems. Also, throughout, extreme care must be taken to protect the wall paintings and statues. In fact, the work can't be done without local craftsmen. The Newars had no thought of teaching carpentry to the Lobas -- only conservation, which requires materials such as concealed metal rods and plates to reinforce a structure that simply can't be straightened. Part of the building's load imbalance resulted from the 1815 restoration, when most of the north wall appears to have collapsed and was rebuilt inward the width of a row of columns (reducing the number of columns from 49 to 42). A near perfect square had been turned into a tentative rectangle, and the asymmetrical loading had contributed to the warping of many of the timbers. At one location, the Newars needed to re-set one joist on top of a column, and do so slightly off of center, similar to its position when found. It took a town meeting and some explaining from John that, even without the concealed metal reinforcement, this would actually be more stable than trying to re-align an area of the building that had been distorted for centuries. For Lobas and Newars, the roles have now been well defined, and the two groups of carpenters are working together smoothly. Throughout, nothing has slowed the volunteer townspeople, busy carrying mud for a new roof and slate for copings atop the roof's boundary walls. BACK TO THE FUTURE "We need you here," the Raja told Sanday, impressed by the value of the work completed thus far and sympathetic to the team's difficulty in getting travel permits. He promised to help push the process in Kathmandu, but added, shrugging, that "in the new era of democracy kings just don't have the clout they used to". "The most important part of our work is the training of local people," Sanday said, "and doing so largely in situ -- the best place. We hope to instill high standards, along with a high level of skills. Ultimately, strong religious faith, a good maintenance program and a trained, professional work force can keep at least this part of their culture alive indefinitely." Sanday returned to Kathmandu with his carpenters for the Nepal's fall holiday season, and again requested an audience with Tri Rimpoche, who is both the maternal uncle and root guru of the Raja. This time Rimpoche pulled out Rs. 1,700 ($25), sufficient to buy John and his entire team tea and food on their next trip to Mustang. Rimpoche then promised to commission some prayers for the ongoing success of the restoration - and for the goverment to grant travel permits. Dharma, the path of compassion and perfection, will survive, in Mustang, and hopefully so will Thubchen gompa and other ancient, precious monuments. The Lobas' lives are punctuated by ritual and natural events, and their monuments are expressions of this -- jewel-like manifestations on earth of both nature and divinity. Copyright Broughton Coburn 1998 |