asianart.com | articles

Download the PDF version of this article

Reviewed by Freya Terryn, KU Leuven [1]

Images © the publisher Hémisphères éditions

Published December 15, 2020

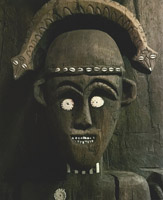

Fig. 1

In this collection of twenty-eight essays scholars and specialists in the art world identify the types of collectors of Asian art, the purchased Asian art works, and the mechanisms at work in constituting Asian art collections from the 19th century onward (Fig. 1). By devoting significant amount of space to the discussion of not only art collections, but also craft collections and those constituting out of artifacts of daily, popular, and ritual use, the editors of the present volume succeed in enriching our understanding of the artistic and cultural exchange taking place in art collections across Asia and the West.

While the above goal is shortly stated in the introduction of the volume, the collection of essays would have benefitted from placing itself more into context and acknowledging the contributions of previous scholarship to the field. Considering that, for example, Michael North’s edited volume Artistic and Cultural Exchanges Between Europe and Asia, 1400-1900: Rethinking Markets, Workshops and Collections (2010) discussed the movement of material goods and ideas between Europe and Asia during the first five centuries of sustained European contact until 1900, Laureillard and Patin’s edited volume deftly continues a similar discussion with essays focusing on the movement of material goods – while fixating on the formulation of both public and private collections – from the 19th century onward.

The volume identifies and examines these various collections by means of its four chapters, each from a different viewpoint: of the collector (first chapter), of institutional and collective collections (second chapter), of the art market (third chapter), and of overlapping perspectives (fourth chapter). This clear structure gives the edited volume a solid backbone and allows for easy browsing through the diverse array of collections and viewpoints. Each chapter is also accompanied by a section of colored illustrations – a total of 72 pages in color – adding to the richness of the volume.

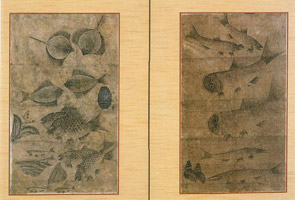

Fig. 2

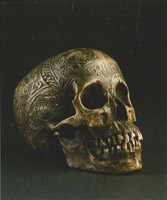

Fig. 3

In the first chapter the profiles and motivations of various collectors of Asian art are considered. An analysis of collection strategies and personal motivations demonstrates how a collector’s infatuation with historically neglected art objects can contribute to their reevaluation within art history, as presented in Marie Laureillard’s essay on Yang Ermin’s collection of ink stones (Fig. 2) and Okyang Chae-Duporge’s analysis of Lee Ufan’s collection of Korean popular painting (Fig. 3). A collection can likewise contribute to and celebrate the multiple identities of society, as argued by Paul van der Grijp in his case study of three private Taiwanese museums, while Astrid de Hontheim demonstrates how a collection offers his collector an escape from his own society and daily life by taking up Asmat art collectors. Similarly, through Christophe Comentale and Marie Laureillard’s analysis of François Dautresme’s collection of Chinese objects of daily use, it becomes clear that a collection can also be viewed as a lieu de mémoire of the collector himself. Finally, Nicola Foster illustrates how the value of modern and contemporary art depends on the distinctions between ‘donation,’ ‘swap,’ and ‘monetary exchange’ and their placement in art history by analyzing Uli Sigg’s collection of contemporary Chinese art.

Fig. 4 |

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8 |

Fig. 9

Fig. 10 The role and influence of the art market is evaluated in the third chapter. Léa Saint-Raymond creates an understanding of how taste for Asian objects evolved in Paris by analyzing public auctions between 1858 and 1939, profiling both prominent and unknown collectors. Two Japanese auction houses are scrutinized by Cléa Patin to expose the challenges they face in contrast to well-established art galleries, such as their incapability of providing counterweight to price variations and their inability to guarantee the authenticity of art work. Then Laurent Schroeder demonstrates how Chinese collectors and private museums have changed the value and position of Chinese art in the art market since 2000. The strong affiliation between politics and the act of collecting art is exposed in the essays of Christa Adams, who argues that the collection of ancient Chinese jewelry and adornments lends to collective reaffirmation and reappropriation of an idealized past reflecting Xi Jinping’s promotion of “patriotic acquisitions” (Fig. 9), and Serge Dreyer, who analyzes the profile and motives of collectors of Hoklo and Hakka art (Fig.10). Hakka art is further considered by Lo Shih-Lung as he clarifies which collections can enter museums, which are considered Hakka, and what image of Hakka is presented in collections of three Hakka museums in Taiwan. Hereafter Li Shiyan investigates the art gallery ShangART of Lorenz Helbling and Helbling’s activities through an analysis of three Chinese notions of opportune moment, geographical advantage, and the harmony between men. Wang Hongfeng completes this chapter with his study of private art museums in Shanghai disclosing their ambiguous position due to their absence of public service, lack of regulations, and legal status as private museums without lucrative goal.

In the last chapter essays approach Asian art, collections, and collectors as a transcultural encounter. Oikawa Shigeru pauses at the reception of Japanese woodblock prints during the rise and height of the Japonisme movement by addressing how, when, what kind of prints circulated, what role auction sales played in their reception, and what prints were included in contemporary paintings (Fig. 11). Next, Liu Chiao-Mei introduces the Chimei Museum, its collection of Western artworks (Fig. 12), and how it succeeds in maintaining close links with academic institutions and offering scholarships to graduate students. The evolution of corporate collections of Western art in Japan from the Meiji period onward is examined by Shimada Hanako, who demonstrates how Ōhara Magosaburō, Matsukata Kōjirō (Fig. 13), and Ishibashi Shōjirō contributed to the introduction of Western art in Japan before the opening of national museums. Christine Vial Kayser introduces the Chinese Art Initiative and how it poses questions regarding the respective roles of the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation and the Guggenheim in choosing members of the committee in charge of selecting artists and the plausible refusion of certain commissioned works to enter the collection. Franziska Koch concludes this volume with her examination of the dslcollection in which she systematically identifies the ‘problems’ of its virtual mode of presentation that ultimately guarantee the transcultural potential and the creative social power necessary for the collective reorganization as well as the perpetuation of the transmission function of the art museum in a globalized and technologically connected world.

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 12 |

Fig. 13 |

Notes:

[1]: PhD Fellow, Research Foundation – Flanders.

[2]: Take, for example, her monograph Travel, collecting, and Museums of Asian Art in Nineteenth-Century Paris (2013) on the founder of the museum and the formation of the museum’s collections.

asianart.com | articles