asianart.com | articles

Articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

Download the PDF version of this article

Indian Art “Auditions” in Hollywood exhibition

images © Los Angeles County Museum of Art except as where otherwise noted

May 11, 2017

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

1

I must have been about 10 when I saw my first Hollywood movie. It was Charlie Chaplin’s “Gold Rush” and it was awesome. Thereafter, at my Catholic boarding schools, Hollywood movies were our regular fare for entertainment, especially Westerns.

My initial encounter with the place occurred on my first visit to Los Angeles in the summer of 1964: I must admit the tiled star-studded stretch of Hollywood Boulevard and the Grauman's Chinese Theatre (as it was then known), were not what I expected of Tinseltown. There really was no arcadian, territorial Hollywood; only a state of mind. In any event on that initial visit, as I did walk the walk of fame on Hollywood Boulevard, I never dreamt that I would one day work in the neighborhood or meet any real movie stars.

Phil Berg Curiously my first encounter with a Hollywood personality occurred at the Boston Museum in the fall of 1969 when I had already announced my departure for the west coast. One day I got a phone call from Nasli Heeramaneck (1901–1971), then the leading dealer of Indian art in New York, that a gentleman called Phil Berg (1902–1983) would be visiting me and that he was a collector of Indian art. A few days later Mr. Berg arrived at the Boston Museum; he was a robustly built elderly gentleman with a very ruddy face and a deep-throated voice that were a little disconcerting.

His brusqueness became apparent within a few minutes of our introduction when he declaimed that I was making a great error by joining the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). I must say this was quite unnerving, as only a few days ago I had had a similar discouraging message from Sherman Lee (1918–2008), the famous director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, about the move to Los Angeles. When I asked Phil Berg the reason for his admonition, he went into a tirade, and, as his face turned redder and redder, he berated LACMA trustees and painted a grim picture of my future. Anyway, after he ran out of steam, I learnt that he was a global art collector, including Indian art, and was going around the country visiting the major museums.

Not heeding his or Sherman Lee’s cautionary advice, I did make the move and soon after joining LACMA was invited to the Berg casa in the Hollywood Hills to see his collection. I also learned that he was a retired and well-known Hollywood film agent and his most famous client was Clark Gable. It was at his house that I met Karl With (1891–1980) who was a noted art historian and an émigré from Germany. He too was not well disposed towards LACMA because he was a close friend of Berg and one of his advisers for the collection, though I always wondered if anyone could really advise the irascible Hollywood agent who took care of mega stars.

Decades later in the early years of the new millennium I came across a memoir of Karl With from which I gleaned some interesting information about Phil Berg [1]. In Germany With was an eminent figure in the art world in the 1930s after his studies in Vienna with the famous scholar Josef Strzygowski (1862–1941). A decade earlier With had already become well-known for his contributions to the arts of China and Japan. After a distinguished career in German museums he was dismissed by the Nazis in 1937 and escaped to Ascona, Switzerland to work for the famous collector Baron von der Heydt (Eduard Freiherr von der Heydt1882–1964). Finally, in 1939 With moved to the United States and with the help of friends found himself in Pasadena where he joined the recently founded Graduate School of Design by Walter Baermann (1903–1972). The following year he left for the east coast but returned in 1948 with an appointment as a guest lecturer at USC and UCLA. He remained until his death in 1980 an active figure in the California art world and worked closely with Fred Grunewald (1898–1964), the collector of graphic arts, whom he met at an exhibition of Degas lithographs and drawings at the old LACMA in Exposition Park, and also Phil Berg, the encyclopedic collector. In his memoirs With wrote glowingly about his friendship with Grunewald and then began his recollection of Phil Berg as follows:

As a collector Phil Berg was not like Fred Grunewald, a specialist in a given field, but an universalist… His aim was not primarily an aesthetic but a didactic one… [2]Pertinent also is With’s opinion about Berg’s personality which explains his difficulty with LACMA, as expressed to me on our first meeting in Boston and to be recounted shortly below.

He is sharp [writes With] and quick of perception, argumentative and unbending in his, at times, opinionated views. Whenever his opinion or judgment was challenged or contradicted he would wage a verbal and intellectual war…Before LACMA moved to its new premises on the La Brea Tar Pits in 1965, Berg and With had unsuccessfully attempted to build a museum in Beverly Hills. This effort failed when the new art museum (LACMA) was established on the border of the two cities. Graciously, however, Berg promised to donate his collection to it, which was an encouragement to the fledging institution. In recognition he was elected to the board but apparently at his second board meeting there was some sort of an altercation between him and another trustee and, in the words of With, not heeding the “conciliatory way of polite tactfulness,” Berg exploded and threatened to resign. Apparently, fellow trustee Sydney Brody immediately commented, “resignation accepted,” and as another trustee seconded the motion promptly, Berg was off the board.

However, the donation of his collection to the museum must have been a done deal for soon after I joined the museum in 1970 we learnt that an exhibition of his collection with a catalogue by Berg himself was going to happen. So it did under the curatorship of Rex Stead (the Deputy Director in 1971) with the title Man Came This Way, though not without another unpleasant incident [3].

One morning while we were at our regular monthly curatorial staff meeting chaired by director Kenneth Donahue, suddenly the doors flung open and in charged Berg with the reddest face I have ever seen like a glowing, setting sun. He rushed towards Donahue while rambling incoherently and rolling up his sleeves. Donahue jumped up from his chair and, in a show of uncharacteristic belligerence for him almost shouted back at Berg accepting the challenge. We thought a fistfight would ensue but, calming down, Donahue then escorted him to his office where he assuaged Berg’s anger which was due to some minor problem with the ongoing installation of his show.

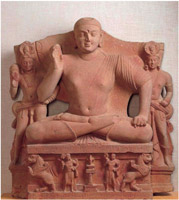

Fig. 1I illustrate here two Indian sculptures from the Berg Collection [4]. Both were acquired from his friend Nasli Heeramaneck, who, however, did not live to see the exhibition. Since it is auspicious for a Hindu to begin any enterprise by invoking the popular elephant-headed god of India, I will start with a charming stele in phylite of a dancing Ganesha from twelfth century Bengal (fig. 1). Crisply carved, the elegant child god dances gracefully on the back of his rodent vehicle to music by two attendant musicians on the base. A pair of flying celestials above his head approach him with two floral garlands and a cluster of mangoes symbolizing abundance directly above his head at the apex of the stele serves as a parasol.

Fig. 2The second sculpture is no less charming and is carved from marble, the popular material in Rajasthan (fig. 2). Executed probably a century later than the dancing Ganesha, it too is a lively composition that depicts in a more rigidly linear style a diminutive youth boldly stretching his left arm to reach the cornucopia or horn that a larger lady holds with her raised right hand while her left hand firmly grasps his stiff outstretched hand. The erotic innuendo of the interaction between the two figures, the contrast between the precocious adolescent and the Amazonian female and the ambiguity of the movement of his arm (is he attempting to grab her breast or the drinking horn?) emphasize the playful and droll nature of the representation. Originally the sculpture served as a bracket placed atop a column in an assembly hall, perhaps of a Jain temple, while the Ganesh stele adorned a niche on the outer wall of a Hindu shrine.

One of my major tasks upon joining LACMA was to add a few Chola bronzes to the collection. For some reason, this much admired –and justly so—form of Indian art was poorly represented in the otherwise comprehensive Heeramaneck Collection. So I began looking for suitable material at reasonable price as I had no illusion about raising the funds required so soon after the 2.5 million dollar Heeramaneck purchase; Chola bronzes of good quality have always commanded high prices.

Fig. 3As luck would have it, shortly after I joined the museum Robert Ellsworth, a dealer in New York, offered me an opportunity that seemed ideal for my purpose. The offer was not of one Chola bronze but a group of four metal figures of impressive size. Consisting of Krishna as the Rajamannar (King of the Cowheards), his two wives Rukmini and Satyabhama and the hybrid (human and avian) Garuda (his vehicle), the group was not only iconographically complete but also extremely rare. Moreover, they were well preserved, well proportioned, elegantly modeled and attractively patinated, making for an appealing and affective assemblage. The quartet had a great provenance (though this was not a problem then as it is now), as they were part of a Swiss private collection formed in India in the middle of the last century. (fig. 3) [5].

Fortunately, thanks to Trustee Ms. Katie Gates the funds came from a fellow trustee who had been appointed that summer. He was Hal B. Wallis whose name I knew from my early youth in India. He was not only the producer of the film “Casablanca” which had acquired cult status by the 60s but had also made several movies with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis and with Elvis Presley whose fan I had always been. The price for the group was $150,000, which was a substantial sum in 1970, especially considering that the highest priced sculpture in the Heeramaneck Collection was only $50,000. At a lunch meeting in the museum café, Katie had wryly commented that the amount would be a modest initiation fee for Wallis to join the exclusive club. So the group was bought even though Wallis had no interest in Indian art per se. His personal predilection was for Impressionist painting.

Director Donahue then encouraged me to write a monograph on the group, which the museum published in 1972 (see bibliography). I remember visiting Hal Wallis’s home in Westwood one morning with a copy of the monograph. He himself opened the door (there was no butler) to a large house with a circular atrium. As I handed him the publication he called out to his wife, the actress Martha Heyer, who, as in a Hollywood film scene, appeared on the balcony above the rotunda with a telephone, which she cupped and whispered: “Hal, it’s Cary [Grant] on the line and it will be a while” and disappeared. I never did get to see her on that visit but Hal was pleased with the monograph.

Hal Wallis never bought another piece of Indian art but we did meet on other occasions at various social gatherings. At one reception of an exhibition opening when the Watergate scandal of the Nixon administration was just breaking out, I made the suggestion that it was a good time to make a film on the famous impeachment of Warren Hastings towards the end of the 18th century in England [6]. I am afraid the Republican Wallis was not amused and so ended all my hopes of becoming a consulting Indian historian for a Hollywood movie. As an aside, I must say, considering what is happening in the country today, in those days the political affiliation of a trustee, (most of whom were Republicans) did not matter.

Fig. 4To return to the Wallis gifts, except for the figure of the Garuda, the mythical sunbird who is the mount of the Vedic deity Vishnu and is thus of greater antiquity than Krishna who became identified with Vishnu and hence inherited the avian vehicle, the three principal figures are essentially given human forms, albeit as regal personalities (fig. 4) [7]. Krishna is a lordly presence standing in the graceful thrice-flexed (tribhanga) stance and once held the attribute of a shepherd’s crook with his right hand, the only indicator of his cow-herder profession. Of the two spouses the younger Satyabhama is clearly the favorite as Krishna’s left elbow rests on her shoulder, while Rukmini stands slightly aloof as befitting the principal queen. The Garuda’s mythic form is indicated only with a beak of a nose, two prominent fangs and a pair of wings grafted on his shoulders, while his devotion is expressed by the reverential gesture of his hands, as is usually the case with the simian attendant Hanuman in the group of the epic hero Rama. Noteworthy are the subtle formal differences that distinguish the two ladies in their figural proportions, hairstyles and other accoutrements. All the four figures are united, however, in a harmonious composition, no matter their individual and nuanced iconographic and formal differences. Not only do they constitute a subtly interactive and sensuously but dignified foursome, but, as far as is known, their completeness, their brilliant blue-green patina from long burial in the ground and their individual persona make them an uncommon group in the corpus of three glorious centuries of metal-casting in the history of Chola art.

It was I think in 1971 that I met another and younger Hollywood

Michael Phillipsproducer who, however, became not only a serious and avid collector of Indian art, but a generous donor to the museum. His name is Michael Phillips and over four decades later we are still friends. Michael was then an active movie producer with such titles as “Taxi Driver” and “The Sting” to his credit and who, a little later, would be a co-producer of “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” directed by Steven Spielberg.

I met Michael through his father Lawrence (Larry) Phillips of New York who was in the textile business and began collecting Asian art in the late 1960s [8]. I think we met late in 1970, or early in the following year, when Larry visited LACMA and introduced himself as a dealer. He also told me then about his son Michael who was in the movie business and lived in Beverly Hills. Shortly thereafter I visited Michael’s house to see his collection, which consisted mostly of sculptures in stone and metal from India and Southeast Asia, obviously influenced by his father. I remember long discussions about the philosophy of collecting and how he wanted to be a focused collector rather than an opportunistic or serendipitous one. He further averred that his personal preference was towards Buddhist art and asked what I thought if he limited himself mostly to Buddha images. I concurred that it was a great idea, and, thus encouraged, he began acquiring with gusto. Rather than being an amasser of objects, he became deeply interested in both the history and spirituality of Buddhist art, unlike almost any other collector I have known in my long professional career. Incidentally, he is a yoga buff, as well, and, like many of his Hollywood colleagues and stars, is a practitioner of Bikram Yoga. I also knew Bikram Chaudhury, (a fellow Bengali from Calcutta [now Kolkata]) and perhaps the most famous, (until recently) yoga master with the Hollywood crowd.

Apart from providing intellectual sustenance to me personally –not abundant in Hollywood– Michael Phillips was a steady supporter of the department and also a regular donor to the museum. Those interested are invited to look up the several volumes of the catalogues of the museum’s Indian and Himalayan collections or to visit the museum’s website to peruse his many gifts. I include here two Indian stone images of the Buddha that he parted with in the 80s as they are of considerable art historical significance.

One is a fragmentary standing Buddha, presently 48.2 cm. high, but, when complete with head, halo, feet and the base, would likely have been twice as high or a foot and a half taller and hence of impressive size (fig. 5). It is almost certainly a sculpture belonging to the transition period (ca. 300 C.E.) between the high Kushan style (2nd–3rd century) with its heroic majesty (as seen in a seated Buddha image to be discussed shortly) and the Gupta period (4th-5th century). The second example is a complete stele of the fifth century of the Buddha preaching at Sarnath, as is evident from the gesture of turning the wheel of law and the literal depiction of the wheel on the base (fig. 6). In the catalogue written thirty years ago I tentatively suggested the Bodhgaya region in Bihar as the sculpture’s source and broadly dated it to the Gupta period [9]. I see no reason today to change my mind and, while still intrigued by its stylistic features, consider it to be a work produced in the region between Sarnath and Bodhgaya.

Art historically significant as these two Buddha images are for the LACMA collection, aesthetically, the most spectacular representation of the Buddha that was once owned by Michael and that got away from Hollywood to Texas—just as a great deal of corporations have done in recent decades including movie making – is an inscribed dated stele of magnificent proportions, which has a fascinating history that I feel ought to be made public now. Today the Buddha is one of the stellar objects of the illustrious collection of art at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas (fig. 7).

I first saw the sculpture along with another similar stele in London in the early 80s. Recognizing its beauty and art historical significance I immediately selected the Kimbell piece and had it sent out to LACMA determined to acquire it. It sat in my office, usually with a covering, as I did not want every Tom, Dick and Harry who came to the office to see it. I must have enjoyed the Buddha’s company for at least six months or more, but, alas, failed to find an angel in the city of angels. Knowing Michael’s interest, I did show it to him with the clear understanding that the museum had the first refusal but if I failed to find funding he was welcome to it.

So it happened and I had to release it to Michael who was just as smitten by it as I was. The Buddha moved from my office to Beverly Hills. My consolation was that at least the magnificent figure would remain a neighbor and may even one day return to the museum. Michael set it up on the mantle shelf above the fireplace of his spacious living room and I must say, it was perfectly positioned, as if on a high altar in a shrine, looking down benevolently at the viewers.

It was that Buddha image, dedicated during the reign of the Kushan Emperor Kanishka I of the 1st–2nd century C.E., which inspired me to organize an exhibition about the Master entitled “Light of Asia” in 1984 but unfortunately the sculpture was not available. The Buddha was also the reason why I met one of the movie moguls of Hollywood, the famous Steven Spielberg. At a party at Michael’s house, we were introduced in front of the statue and I was requested by the host (as prearranged) to say a few words about its importance in the hope that it may kindle interest in Indian art in the wealthy moviemaker. He listened to my mini sermon patiently but was not converted; he looked around the large room filled with people and asked why the Buddha was not receiving more attention.

I had no answer though I was reminded of the sardonic lines of the Anglo-American poet T.S. Elliot in the “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” “In the room the women come and go/Speaking of Michelangelo.” But I knew if Michelangelo could see the Buddha he would have admired it, as was the case with Rodin’s love affair with the Nataraja.

Ultimately sometime later the Buddha decided to move again and this time to the Kimbell Museum at Fort Worth, Texas. Ever since Richard Brown, the director who, after overseeing the opening of the new campus of LACMA at the La Brea Tar Pits in 1965, himself moved the following year (due to disagreements with the LACMA board) to the Kimbell, that museum had acquired a reputation not only for collecting high quality art selectively from all major cultures globally, but also for its beautifully designed building by the celebrated architect Louis Kahn. It was rumored that when Rick (as he was popularly known in the profession) left LACMA in 1966, he also took with him some great objects that were on offer to the museum but were yet to be acquired. By the time the Kimbell acquired the Kushan Buddha, Rick had died, but I guess his spirit was still active, or, as I sometime think, even though inanimate, objects of art do have a volition of their own.

Michael Douglas If Michael Phillips and I failed to lure Spielberg to the den, Michael was instrumental in introducing another eponymous Hollywood character. He was Michael Douglas who had just completed his popular TV series “The Streets of San Francisco” and was starting a career in the movies. The common link was Rob Harabidian who was originally the accountant to actor James Coburn and Phillips who directed Douglas to Harabidian who was an expert in the matter of art donation. A word of explanation is necessary here for those who are not familiar with art and the American tax system, as I was not until I joined LACMA.

In America one is allowed a tax break if one donates any tangible property to a charitable institution. Thus, if one gives away a car, a home, or a designer dress to a bona fide non-profit, then one can deduct the current market value of the gift at the time of the donation, no matter what the purchase price was. The minimum period of possession is a year from the date of purchase before one makes the donation. Thus, if one buys an object today for say $100 and after a year it is worth $150, according to the fair market value, then one can deduct the latter amount from one’s gross income. This is a great way for museums to augment their collections and, I believe, a win-win situation for both parties provided one does not abuse the privilege. Unfortunately people do, as I discovered during the 80s when I was inducted by the Internal Revenue Service to serve in the IRS Commissioner’s Art Advisory panel in Washington D.C. for a decade. The committee met twice a year in the capital to evaluate donations red flagged by regional IRS officers with guidance from inspectors in the Commissioners’ office. It was a great learning experience and I am happy to report that I encountered hardly any questionable gifts of Asian art to LACMA. That it was a fair process is demonstrated by the fact that, while some of the donations were deemed to be excessively valued, we also persuaded the IRS, at my suggestion, to increase the monetary value of undervalued objects and inform the relevant donors. So on the whole it was an equitable situation for everyone concerned and encouraged collectors to augment public institutions.

For the first couple of years after the telephone call from Rob Harabidian, I continued to find objects for Michael Douglas but never met him. All the transactions were between Rob and me over the phone. Then one day in 1979 when I was the acting director at LACMA, I got a call from Michael who requested a meeting. So we first met at LACMA, and I was impressed by his amiability and lack of affectation. He revealed no sign of his Hollywood celebrity and told me candidly that his own interest was in American art but because the market in that area had exploded, the art was now beyond his reach. He also admitted that he knew nothing about Asian art and that he would like to leave the purchases to my discretion and I should continue to buy what I thought was needed to augment the collection. I then showed him the Indian galleries and gave him a brief history of the collections. As we said goodbye he said he would call me when he was free and perhaps we could have lunch.

Thereafter, we did meet occasionally at his favorite restaurant, which was the dining room of a small hotel on the border between Beverly Hills and Los Angeles. It was not a gourmet place but quiet and cozy and I guess free of paparazzi. When we first met, he was a bachelor, but then he married Diandra Luker and bought a house in Montecito near Santa Barbara (he was an alumnus of the university there where I used to teach art history occasionally). I also have vivid memories of visiting the Montecito home once or twice. During the 80s when he became a better known and sought after film star, he was away a great deal and our encounters became less frequent but Diandra showed an interest in Indian art. On one occasion I drove her to Palos Verdes to look at some paintings offered by an itinerant dealer. This was her first experience with Indian paintings, but she was quite perceptive and had a good eye. She acquired a bunch but I don’t think they ever came to the museum.

On that journey to Palos Verdes I realized that Diandra was quite agitated as it was just after Michael’s film “Romancing the Stone” had been released and there was a lot of gossip about his own romancing the leading lady in the film. Diandra was of course aware of the rumors, which I think was the cause of her moodiness. On the way back, she suddenly requested me to drive to a car dealer in Santa Monica, where, in less than an hour, she selected a car, called Rob to arrange for the payment and after thanking me, drove away. It was the fastest car purchase I had ever witnessed. I never met her again. I did meet Michael once more only by accident at LAX as I was waiting to receive a guest inside the American Airlines terminal (in those days when there was no fear of flying) and we exchanged cordial greetings. Soon thereafter Michael and Diandra separated and he moved to New York.

However, some of the objects that I had bought for him and were on long-term loan were given to the museum over the next few years and from these I illustrate here two Indian paintings. In fact, pictures rather than three-dimensional objects were his preference, which allowed me to fill many a gap in the collection. One of the pictures is included in vol. 1 of the museum’s catalogue of Indian paintings published in 1993 and again in the catalogue of the landmark exhibition of Jain art the following year [10]. It is a rare picture from the Deccan, that augments the modest group of such works in the Heeramaneck Collection acquired in 1969, as well as for its unusual subject.

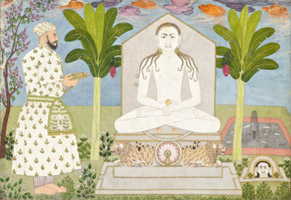

Fig. 8The painting is a fine example of the Golconda school of the last quarter of the 17th century when local artists had begun to absorb Mughal stylistic elements (fig. 8). Uncommon is the subject matter of the hieratic and formal composition with a muted but sophisticated sense of coloring. According to an inscription on the back, the devout figure with offerings is Rai Jabha Chand, a nobleman, who obviously was of the Jain faith notwithstanding his attire. The image he adores is of the enthroned Rishabhanatha, the first of the 24 emancipated teachers of the Jains. Noteworthy are the whimsical rendering of the two lions with the stripes of the tiger making them early versions of what are known today as “tigons” and the kudu arch at the lower left enclosing another head only of the savior.

Fig. 9While the devotional portrait of the Jain merchant in the conventional format on paper of what is frequently though inappropriately characterized as a “miniature,” the second Douglas gift is by contrast a monumental portrait on cloth of a Rajput ruler (fig. 9). It is a formal portrait of Maharana Jagat Singh of Mewar (reigned 1628–54) painted in the third quarter of the 18th century. While the formality and style of the portrait is ultimately derived from the Mughal tradition, showing the ruler both as a valorous man by the axial positioning and the firm grasp of the long ceremonial sword, the artist has also portrayed him as an urbane aesthete as he smells a nosegay (lilakamala) of roses. What further distinguishes it from the portable portraits on paper is the larger than life size representation on cloth, undoubtedly used for ceremonial purposes on special occasions.

James Coburn in Magnificent 7 Another Hollywood couple that I met partly through accountant Harabidian and partly due to one of my itinerant hippie dealer friends was James and Beverly Coburn. I think my first encounter on the screen with James, which impressed me, was the cool, gritty, knife-throwing character he played in the movie “The Magnificent Seven.” He too was mentioned by Harabidian as someone who wanted to make annual donations to LACMA for tax purposes. The Coburns were already familiar with Asian art before I met them. Beverly was friendly with several young European itinerant dealers and one day she called me at the museum and invited me to come to the house in Beverly Hills to see what they had already acquired.

I will never forget that first visit when I saw a sweaty James chopping wood under the warm southern California sun in the garden. This was one of his means of staying fit, which he remained until the end of his life. As I walked up the driveway towards the house, James stopped chopping and asked if he could help me and I introduced myself. He was very welcoming and apologized for not shaking my hand as he was dripping with sweat and told me to just push the front door and go up the staircase. I did as instructed and there, on the second floor in a spacious room, decorated, I think, in a distinct oriental style with rugs and bolsters, was Beverly in a house coat and enveloped in smoke from a cigarette and burning incense. It was a typical Hollywood scenario and clearly that was her favorite room in the house for whenever I went that is where we assembled. I never saw James again in the house but he did come to the galleries in the museum occasionally and always dropped by to say hello. Once he attended a departmental dinner at an exhibition opening with their young daughter, who obviously had inherited her mother’s good looks. The year before I left the museum in 1995, I met James for the last time in the galleries with another beautiful young lady named Paula. I don’t remember whether they were already married by then, but now the James and Paula Coburn Foundation is a major supporter of film programs in the community.

James & Beverly Coburn James and Beverly seemed to buy independently and I had more contact with the latter than the former. While both preferred Himalayan art in general James also acquired Indian objects. One of the most impressive Indian sculptures that he gave to LACMA in 1982 is a rare and unusual 10th–11th century representation of Shiva as the supreme teacher (fig. 10). Carved from granulite, the figure lacks the usual signs of divinity such as four arms, and could well be a portrait of a mortal ascetic, though the fan like spread of his hair behind the head also symbolizes the halo and the luxuriant ornaments transform him into a rajarshi (royal ascetic) rather than a rishi [11]. The second object is of a much later period and made of metal (fig. 11). It too is an unusual representation of Shiva but from the Himalaya, which is the abode of the deity. The object probably covered a simple stone Shivalinga, thereby transforming an abstract symbol into a suggestive anthromorphic image. The five heads, each distinguished by the third eye and serpent crests, symbolize the four directions and the center, thereby emphasizing the god’s cosmic nature.

While some of Beverly’s objects appeared in public auctions a few years ago, it is gratifying that James left the bulk of the collection to the museum. Most of these objects are examples of art from Nepal and Tibet and can be viewed on the museum’s website.

There were (and perhaps still are) other collectors of Indian art in Hollywood but I did not know them well and was unfamiliar with their collections. Two of these collections of Indian paintings were ultimately sold [12]. One collector who was happy to show his modest collection of Rajput paintings was the well-known modern artist Richard Diebenkorn (1922–1993). Though not a Hollywood personality, he lived at the northern end of Santa Monica. I did enjoy my solitary visit with him (he was a soft-spoken and congenial man) and remember well his enthusiasm particularly for the Malwa school of Rajput pictures which were not very popular with collectors. I have, however, always liked their simple, geometric compositions, strong forms and bold colors, which also appealed to Diebenkorn. Again I did not visit him with a camera but through a friend was able to discover a photograph on the web and illustrate it here (fig.12) [13]. In it we see a fine example of the Malwa school of painting hanging on the wall above the artist’s head, as he sits with his sketchbook.

Lizabeth Scott Three other Hollywood actors who were not really collectors of Indian art but became associated in interesting ways were Lizabeth Scott (1922–2015), Charlton Heston (1923–2008) and Gene Kelley (1912–1996). Lizabeth Scott was a contemporary of Jennifer Jones but perhaps not as well remembered by today’s generation of movie buffs. She was a pretty and petite blonde with a rather sultry look and deep bass voice and was often cast as the femme fatale in classic noir films after WWII. Her image had stuck in my mind from the 1950s when I was a keen viewer of Hollywood noir with its tough guys and droll dolls cliché characterizations. Liz (as she was known to friends) became a personal friend of both my wife and myself and we socialized together as we did with Michael Phillips. Besides, as she was already retired when we met, she was more actively engaged with the museum than the other Hollywood personalities.

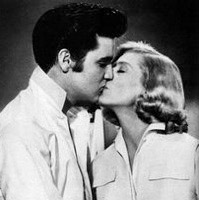

Lizabeth and Elvis, Loving You, 1957 I met her for the first time in 1979 when I was the acting director of the museum for a while. She was a personal friend of trustee Herbert Cole who unfortunately died prematurely a few years later and also of Hal Wallis who cast her with Elvis Presley in one of his Presley films. Liz was a great admirer of Elvis but refused to speak about him no matter how pressed. I remember goading her to write her memoirs but my entreaties fell on deaf ears. She did speak volubly about her movie experience but never about Elvis.

In any event, trustee Herbert Cole was deeply interested in the ancient arts of Asia and was an enthusiastic supporter of the museum’s Ancient Art Council. When the curator of Ancient art left the museum and we decided to wait until the appointment of a replacement, at his request, I agreed to guide the Council. A wonderful man and one of the friendliest trustees I had ever had the pleasure of interacting with, Herb had persuaded Liz to join the Council. That was the beginning of our friendship and the bond only grew stronger after Herb’s unexpected demise.

Liz lived in one of those older picturesque English cottage-like houses on the most winding and narrowest sections of Hollywood Boulevard, not far from another trustee friend, Robert Wilson, and close to the residence of the celebrated Humphrey Bogart of Casablanca fame. (Every time I drove up there to see either Liz or Robert I was reminded of my school days in Darjeeling in the eastern Himalayas where the narrow streets on hilly slopes are as serpentine and treacherous as in the Hollywood hills). Liz personally collected miniature shoes from diverse regions of the globe, which looked very dainty in her very feminine house. She really had no interest in Ancient art when she joined the Council but she was a true trooper and always rose to the occasion when money was required to buy an object. One never had to goad her and she opened her purse cheerfully, which made her, for a curator, an ideal patron.

We continued socializing for several years after I left the museum in 1995 until she approached her ninth decade and became frail. Thereafter, her appearances in public became rare, although her personalized Christmas cards with the message printed in red and signed in green ink arrived regularly until almost her last days.

Fig. 13I illustrate here one of the objects which the museum acquired with funds provided by Lizabeth Scott. It is an illustrated leaf with text from a rare mid fifteenth century manuscript of Balagopalastuti or Eulogy of the Child Krishna [14] (fig. 13). The colorful scene represents milkmaids frolicking with the flutist Krishna in Vrindavana or the forest of Vrinda near Mathura. As I look at it now I think of all those pictures that Hal Wallis made with the guitar-strumming singer Elvis with diverse Hollywood actresses including Liz Scott.

I met Charlton Heston through my friend Carlton Rochell Jr. who is now a leading art dealer in New York, but in the 90s worked for Sotheby’s where he met Holly, one of the Heston daughters. After they married the Rochells visited Los Angeles always for Christmas and we were included in the festive annual holiday party at the Heston house.

Fig. 14Those unfamiliar with Charlton Heston’s name, as Moses in Cecil de Mille’s extravaganza “The Ten Commandments” or from the famous chariot scene in “Ben Hur,” may well remember his large presence on the small screen as the spokesman for the National Rifle Association. However, I must say that while I too was put off by that role of his I did admire him as an actor (he was also a friend of Liz Scott) and certainly at our meetings, whether at the Christmas Party, or at receptions at Sotheby’s in Beverly Hills (see fig. 14) or, occasionally, at LACMA openings, I always enjoyed his company and conversing with him. He was well informed, intellectually curious, courteous and congenial, as was his wife who was an artist whose works were on view in the public spaces at the house.

Heston did acquire one Indian object, however, from Sotheby’s (no doubt under the influence of his son-in-law), which was a schist head of the Buddha from the ancient region of Gandhara (now part of Pakistan and Afghanistan). During the first three centuries of the Common Era the region witnessed a remarkable period of economic prosperity and religious piety, especially for the Buddhist faith. Gandhara was the springboard for the spread of Buddhism north into Central Asia and China, and its art was heavily influence by artistic and aesthetic ideas that came into the subcontinent from the late Hellenistic cultural zone in Iran and further west. The Buddha head of the Hestons is a classic example of the hybrid artistic norms that developed in this frontier region that has always appealed to Western taste (fig. 15).

Fig. 15I got a call one day at the museum and the person at the other end identified himself as Gene Kelly. At first I thought someone was pulling my leg but once the conversation progressed from the content and that distinctive voice, I knew it was really the great actor who certainly was one of my favorites. This was just after the Shivapuram Nataraja of Norton Simon had become a cause célèbre in the 1980s and I had published an article on it in the Los Angeles Times [15]. Kelly said he owned a bronze Nataraja and would I come and look at it. Of course I was thrilled at the opportunity and did go to his home in Beverly Hills. I remember that the front door opened on to a long fairly wide and well-lighted hall along the length of the house (which was more like a cottage rather than a mansion) filled with furniture and art, with the Nataraja prominently displayed on a pedestal along the wall on my right. But what surprised me more than the Nataraja was the star himself. He was exactly like his image in the movies, with the same disarming smile and raspy voice as I remembered from his most memorable “Singing in the Rain.” How appropriate I thought that the unforgettable dancer of the film would own a Nataraja.

Gene Kelly Upon asking him how he came to acquire this fairly large but solitary Indian bronze he owned he told me that he had acquired it as a settlement of a debt owed to him by the famous director John Huston. The story of his acquisition of the object is not quite as simple as my recollection as I recently learnt from a communication from Gene’s widow Patricia [16]. It appears that there is a receipt dated February 4, 1958 from Bill Pearson Fine Art Gallery of La Jolla, CA that Gene bought the Dancing Shiva for $10,000. She also possesses a receipt that it was on loan to the UCLA Art Galleries dated September 4, 1959 for an exhibition. It was not however, included in the 1968 UCLA exhibition of “Art of the Indian Subcontinent from Los Angeles Collections.”

Fig. 16I presumed that he had read the story of Norton Simon’s Shivapuram Nataraja, which was valued at a million dollars at the time and was keen to know the value of his own object. Unfortunately, I had to tell him that his piece, though of good quality, was not as old but of more recent origin. I did assure him, however, that he did not do badly because it would still sell for considerably more than what he paid for it; a Nataraja of that size (45’’H) and well made was still desirable. I could see the slight disappointment in his handsome face but recommended that he get it technically examined at LACMA’s conservation laboratory. I don’t know if he did so, but I never did hear from him again.

Those were before the days of selfies, and, as usual, I did not have a camera with me. If I had, at least I could have taken a shot of the smiling star beside his Nataraja. Alas, a few years after my visit the image, along with other possessions, was destroyed in a fire caused by a Christmas tree. So for those who are not familiar with that particular image, I illustrate here the famous Shivapuram Nataraja of Norton Simon, which finally returned to India in the mid 1980s, but which may have brought Kelly and me together (fig. 16). It is not entirely inappropriate for this article though Norton Simon was not himself a Hollywood personality. For a while, the Shivapuram Nataraja gave him an international celebrity status, and, besides, he was married to the famous Hollywood star Jennifer Jones (1919–2009) whom I also knew well, but their romance with Indian art deserves a separate chapter.

* Acknowledgments: It is a pleasure to acknowledge the kind cooperation of Daniel Ostroff, Michael Phillips, and Shalmali Pal, as well as Doris Jinghuang of Bonhams and Carly Rustebakke of LACMA, and my assistant Nancy Rivera.

Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

Dr. Pratapaditya Pal is a world-renowned Asian art scholar. He was born in Bangladesh and grew up in Kolkata. He was educated at the universities of Calcutta and Cambridge (U.K.). In 1967, Dr. Pal moved to the U.S. and took a curatorial position as the 'Keeper of the Indian Collection' at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He has lived in the United States ever since. In 1970, he joined the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and worked there as the Senior Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art until retirement in 1995. He has also been Visiting Curator of Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art at the Art Institute of Chicago (1995–2003) and Fellow for Research at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (1995–2005). Dr. Pal was General Editor of Marg from 1993 to 2012. He has written over 70 books on Asian art, whose titles include, Art of the Himalayas: Treasures from Nepal and Tibet (1992), The Peaceful Liberators: Jain Art from India (1994) and The Arts of Kashmir (2008). A regular contributor to Asianart.com among other journals at the age of 85+, Dr. Pal has just published a biography of Coomaraswamy titled: Quest for Coomaraswamy: A Life in the Arts (2020).

ENDTNOTES

- With 1997, 321-328

- With 1997, 324 for this and the two following quotes

- Berg 1971. With must have helped Berg with this catalogue. See also Davidson 1968.

- See Pal 1988, 105–106, 114 for more complete discussions and full bibliographical citations.

- See Pal 2015, for a fuller account of this purchase.

- Warren Hastings was the governor general of India in the 1770s and was accused by Edmund Burke for corruption during his tenure after Hastings’ retirement to the U.K.

- See Pal 1972 for a more complete discussion of the group and the theme in Chola art and also Pal 2015.

- See Christie’s Indian, Himalayan, and Southeast Asian works of art New York Tuesday, 13 September 2016, p.68 about Larry Phillips and Little 2013 for an article on Michael’s collection as of the date of publication. Also Pal 1986 and 1988 for the two objects discussed here.

- See Pal 1986, 202, #S79 and 261-62, #S136

- Pal 1993, 345-46, # 108 and 154-55, #113

- Pal 1988, 264-65, #139A and 88, #30

- One of these collectors was Ralph Benkhaim who also like Phil Beg was in the entertainment industry and a difficult man. Ultimately, after his death parts of his collections have been sold. For the Mughal pictures sold to the Cleveland Museum of Art, see Sonia Rhie Quintanilla et. al. Mughal Paintings Art and Stories. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art 2016. The other collectors were William and Gloria Katz Huyck who mostly collected Rajput paintings, which too were sold in an auction at Sotheby’s in 2002, when I first saw their collection. They then formed a second collection of old Indian photographs which they gave to LACMA.

- I am grateful to Edward Wilkinson of Bonhams for bringing this image to my attention.

- Pal 1993 141, #35

- Pal 1976

- Personal communication dated 11/10/2016 with Patricia Kelly through the courtesy of Daniel Ostroff to whom I am grateful also for reminding me of the fire in Gene Kelly’s house.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berg, Phil 1971. Man Came This Way. Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Davidson, J. Leroy 1968. Art of the Indian Subcontinent From Los Angeles Collections. Los Angeles: UCLA Art Council and UCLA Art Galleries

Little, Stephen 2013. Images of the Buddha from the Michael Phillips Collection” in Arts of Asia.

Pal, Pratapaditya 1972. Krishna: The Cowherd King. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Country Museum of Art.

–––––––––––. 1976 The Strange Journey of Shivapuram Nataraja, in Los Angeles Times. Calender, Aug. 25.

–––––––––––. 1986 Indian Sculpture, vol. 1. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Country Museum of Art and Berkeley: UC Press.

–––––––––––. 1988 Indian Sculpture, vol. 2. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Country Museum of Art and Berkeley: UC Press.

–––––––––––. 1993 Indian Painting, vol. 1. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Country Museum of Art.

–––––––––––. 2014 The Last of the Mohicans: Remembering R.H. Ellsworth (1929 – 2014), in Asianart.com.

With, Karl 1997. Karl With Autobiography of Ideas edited by Roland Jaeger. Berlin: Gebr. Mana Verlong.

Download the PDF version of this article

Articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

asianart.com | articles