asianart.com | articles

Download the PDF version of this article

By Maxwell Votey

© author and asianart.com

November 14, 2025

Update Nov. 16 (minor typos)

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Fig. 1Buddhist art in American museums in the 2020s has been in flux. The closure of the Rubin Museum of Art in late 2024 was a tremendous loss for public access to Buddhist art in the United States, yet exhibitions like the Metropolitan Museum of New York’s 2023 show on early Indian Buddhist art, “Tree and Serpent”, and the recent “Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet” have been successful in bringing together rare and important works of Buddhist art and introducing the museum-going public to new scholarship in the field. It is fortunate then, in a time of uncertainty for Buddhist art in America, that the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) has chosen to showcase their extensive collection of Buddhist art in “Realms of the Dharma: Buddhist Art Across Asia.”

This exhibition comes at a time when LACMA is also in a state of change, as much of the museum since 2020 has been consumed in the construction of a new main museum building designed by Peter Zumthor, to be finished in April 2026. This remodel has not been without controversy; not only are there the aesthetic critiques common to any new redesign of a museum but specific concerns that the new museum building will have less gallery space than the buildings it replaces. Among those who appreciate the museum’s significant collections of South Asian and Himalayan art, anchored by the Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck collection acquired in 1969, there is worry about how much floor space will be allocated in the new, smaller museum for those collections.

Fig. 2 Housed in the Resnick Pavilion, one of the two annex buildings kept open throughout construction to house rotating exhibitions and contemporary art, “Realms of the Dharma” comprises 180 Buddhist antiquities—statues in stone, bronze, and wood, thangkas, paintings, and ritual objects from the 1st century BC to the 20th century almost entirely sourced from LACMA’s own permanent collection.

“Realms of the Dharma” is unlike previous exhibitions of Buddhist art at LACMA, such as the major 1984 show “Light of Asia: Buddha Sakyamuni in Asian Art,” in that not only has the museum kept the show’s art to its own collections but also sought the broadest possible scope, showcasing Buddhist art across the entire Asian continent rather than focusing on a single theme, region, or period. This is a daunting task, as few museums could pull together enough objects of high quality just from their own collections for such a show, and there is a vast amount of information the exhibition must impart to educate an average museum visitor both about Buddhism and the nuances that differentiate South Asian, Himalayan, East Asian, and Southeast Asian Buddhist art.

Fig. 3 At the very least, one’s doubts about the quality of the show’s art quickly vanish as one enters the gallery and sees the range of what is on display. The core of the exhibition, and LACMA’s Buddhist art collection generally, is the Heeramaneck collection of South Asian and Himalayan art. Nasli Heeramaneck and his wife Alice, were among the sharpest dealers of South Asian antiquities of the mid-20th century, and built up a 345-piece collection that was acquired by the museum in 1969 for two and a half million dollars, at the time an unprecedented sum for South Asian art and one that the museum would pay off in increments into the 1980s. This acquisition gave LACMA one of the finest collections of South Asian and Himalayan art in the Western Hemisphere.

Access to the Heeramaneck collection alone is worth the price of admission, but there are a surprising number of other South Asian and Himalayan objects acquired by LACMA worthy of a visitor’s attention. The author’s eye was particularly drawn to two such objects, an infrequently published white marble Buddha Shakyamuni from Afghanistan dated to the 8th or 9th century (Figure 1), a particularly interesting example of rare late Buddhist art from Afghanistan before the arrival of Islam, and a 14th century gilt copper Rahu (Figure 2), from Densatil Monastery in Central Tibet, which was razed in the Cultural Revolution.

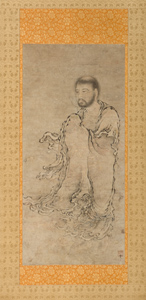

Fig. 4 The strength of the South Asian and Himalayan art however draws attention to the fact that LACMA’s collections of Southeast and East Asian Buddhist art are not as robust. Compared with what is available in collections found in museums east of the Mississippi, LACMA only has a limited selection of Chinese Buddhist art available for the exhibition, though what is shown is still of high quality. This deficiency can be traced as far back to the museum’s (then the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art) abortive acquisition of the Johan W.N. Munthe collection of Chinese art in the 1930s, which was later discovered to consist mostly of forgeries.[1] On the other hand, the exhibition represents an opportunity to showcase LACMA’s growing collection of Korean Buddhist art from both the existing collection and the 2024 donation of the Chester and Cameron Chang Collection to LACMA. Several paintings from the late Joseon dynasty, including a portrait of Monk Samyeongdang (Figure 3) demonstrate the vitality of Korean Buddhist art well into the 19th century—an artistic tradition that, until recently, has been underappreciated in US museums.

The exhibition presents this array of objects decently, and paintings and larger works are particularly well displayed and lit. Many of the largest works are given room to take in both their size and to appreciate them from multiple angles, for example a viewer can fully circumambulate the brilliant 15th century wood Bodhisattva Amoghapasha Lokeshvara from Nepal from the Heeramaneck collection (Figure 4). The paintings in the exhibition, most notably the remarkable Tibetan thangkas from the Giuseppe Tucci (Figure 5 & 6) and Indian collections (Figure 7) also acquired by the Heeramanecks, are well mounted and lit, allowing appreciation of intricate details. This is fortunate, as the variety of early and particularly rare thangkas in LACMA’s collection makes what is shown a world-class selection. However, unlike the large format statues and paintings, smaller works in the show are not similarly well displayed. Small Buddhist sculptures and votive items are placed into oversized cases where the space is not well utilized, and uniformly such items are placed too low in wall-mounted cases for most viewers to closely examine without stooping over. Accessibility is an important consideration, but the bare minimum was done to create accessible displays for these objects, and the result is appealing to no one.

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8 |

Fig. 9 |

Fig. 10 |

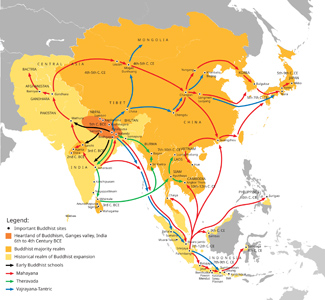

More critically lacking for an exhibition about Buddhist art across Asia is that there are no discussions about the transmission of Buddhism—and by extension Buddhist art—and the cultural and religious exchanges that gave rise to diverse Buddhist art forms across the continent of Asia. Indeed, neither the exhibition, nor the accompanying catalogue, provide a map to orient visitors unfamiliar with the dispersion of Buddhism.

MapBuddhist art is intertwined with Buddhism’s peripatetic spread. Buddhism’s success depended on itinerants: merchants, monks, and artisans. It was merchants, be they the pelagic traders that crossed the Indian Ocean to Southeast Asia or those that plied the camel-laden networks crossing the steppe and deserts of Central Eurasia that linked the Indic, Persianate, and Sinic worlds, that often provided the first encounters with the religion. Monks soon followed, bringing Buddhist texts and teachings to the curious and receptive ruling elites of those distant realms. Yet it was artisans that gave Buddhism its tangible, visual forms that were aesthetically appealing and readily understood, greatly aiding its spread.

While Buddhism would flourish for almost a millennia after the Gautama Buddha in India under the patronage of states such as the Maurya, Kushan, Satavahana, and the Gupta, the religion would be in decline by the end of Late Antiquity. Competition within India by the religious traditions now collectively called Hinduism and the destructive invasions of major Buddhist centers in North India, first from Hunnic nomads in the 4th through 6th centuries AD and then from Islamic Turkic and Persianate conquests from the 8th to the 13th centuries, drove Buddhism to near ‘extinction’ in India by the 13th century.

Fig. 11 However, by that ‘extinction’ Buddhism had already spread and established itself across Asia, spreading like seeds upon the wind (Map 1). Each time Buddhism took root it had to adapt to its new environment. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Buddhist art, where the original artistic forms derived on the subcontinent were transmuted time and again to reflect local cultures and aesthetics. Buddhist art is striking for its adaptability, and that characteristic has been frequently underestimated. Recent archeological findings in China from a 2nd century tomb have evidenced that, less than a century after Buddhism’s first arrival in central China during the Eastern Han Dynasty, local Chinese artists were already adapting Buddhist art from Gandhara into their own, locally produced forms.[2] Buddhist art’s development went hand in hand with the spread of Buddhism to Central, East, and Southeast Asia.

Buddhist art then depends on more than just an understanding of the religion’s doctrine and cosmology, but on its art forms–how those forms adapted to new cultures and how that art evolved over the course of millennia. What is the relation between a 6th century copper Buddha Shakyamuni from India and an 8th century white marble sculpture of the same subject from Afghanistan? The artistic differences are vast despite geographic proximity and the same subject matter. This is to say nothing of works in the exhibition distant in time, space and medium, like the ink painting depiction of Shakyamuni descending from a mountain made in early 16th century Japan (Figure 11). It is studying the similarities and differences of each that one can begin to understand the network of religious and cultural interrelations across time and space that forms the Buddhist world. Tracing that web from one point to another is one of the great joys of studying Buddhist art. None of this is apparent in the show, which is a tragedy. The exhibition’s range is extensive and could be the entry point for many unfamiliar museum visitors to discover the intellectual, spiritual, and aesthetic expanse of Buddhist art.

Fig. 12 This lack of cohesive narrative is also apparent in how some of the art is physically displayed. The art in the exhibition is clustered by region, yet at points pieces from different regions are adjacent without any clear logic behind the placement. For example, in the passageway between early Buddhist and Southeast Asian Buddhist art, three heads are placed together: a 10th century Vietnamese head of Buddha Shakyamuni with two 4th century stucco heads from Gandhara (one of which being a monumental head acquired by the museum in its earliest years, when it was still the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art; Figure 12). The logic behind the placing is practical—showing sculptural pieces from the two different sections of the exhibition that the display straddles—but, without explanation, would only confuse visitors by creating an association between objects not only temporally and geographically distant, but arising from different Buddhist traditions of art.[3] Perhaps such a pairing could lead to a discussion of the connections between the early Buddhist artistic centers in Sarnath and along the east coast of India, from which there was significant cultural and religious exchange with both Southeast Asia and Gandhara. As the display is entirely silent, a visitor can only draw their own associations without context.

The catalogue does a better job providing a general history of the spread of Buddhism, and the specific aspects of Buddhism and Buddhist art unique in each region or country, but again there is little interconnection between the text and the art. The only references to specific works in the show are page numbers in the margins of the text, with the text rarely providing any commentary on the specific work referenced. Understandably, given the scope of what is presented, not every object can have a comprehensive treatment, but the lack of substantive interrelationship between the text and objects is disappointing. Much like the show itself, the catalogue depicts the collection of masterpieces shown attractively (and unlike the physical exhibition, here the smaller objects are accessible) but without a framework to help a reader approach the objects shown.

Despite these shortcomings, “Realms of the Dharma: Buddhist Art Across Asia” is well worth a trip to LACMA for what is on view alone. This exhibition is a worthy effort to reintroduce the Los Angeles public to the extensive collections of Buddhist art housed in their publicly owned, county museum. One can only hope that public interest in this exhibition will increase demand for more Buddhist art to remain on permanent display in the new main museum building—“Realms of the Dharma” demonstrates that LACMA’s collections of Buddhist art deserve such attention.

Footnotes

1. Poundstone, William. 2010 “J.W.N. Munthe, International Man of Mystery” Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, https://lacmaonfire.blogspot.com/2010/04/jwn-munthe-international-man-of-mystery.html

2. Greenberger, Alex. 2021 “Earliest Gold-Plated Bronze Buddha Statues Found in China’s Shaanxi Province” ARTnews, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/gold-plated-buddha-statues-shaanxi-china-1234613494/. The Eastern Han Dynasty dating is contested by some scholars though, see Zhang, Liming. 2024. "Re-Study of the Gilt Bronze Buddha Statuettes Unearthed from the Eastern Han Dynasty Tomb in Chengren Village, Xianyang City, China" Religions 15, no. 12: 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121476

3. In the catalogue this arrangement is not kept, the heads are put into their respective “Southeast Asia” and “South Asia” sections.

asianart.com | articles