|

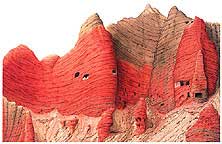

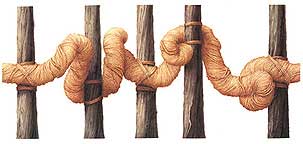

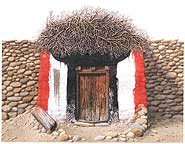

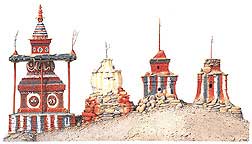

Introduction One day I met Rob resting in a little shelter from the fierce winds that beat mercilessly at the door of Mustang with daily regularity. They descend from the Annapurna into the surrounding valleys to reach the gorges of the Kali Gandaki, the deepest depression on earth. Rob's eyes were sparkling with an inner joy. His words told of an intense experience. He had just seen his artistic imagery translated into reality while wandering in the deserted and multicoloured plateau of Mustang where the mountains are eroded sand and turn into shades of red, blue and green, he had seen the simple rigour of his mental buildings in the cubic, whitish structures of the Tibetan people inhabiting Mustang, and the fantastic forms of his imagery in the windblown broken walls of its ancient monuments. In the landscape of Mustang he finds material suited to his vision. The essential quality of Tibetan structures, their simplicity and the eroded territory serve his style well. The intrinsic sparseness of nature and monuments in Mustang enhance his technical ability to a maximum. He can extract and paint from this emptiness extraordinarily elaborate details, which give substance to his paintings. I have often seen Rob working. I used to sit in his studio, talking quietly to him. Light inundates this space and seems to concentrate on the large white sheets of French paper. A sense of great calm pervades the studio and one senses it in the final results of his work. One thing that strikes me is that his vision is clear before he starts painting, and this clarity accompanies him throughout his work. His skill helps him to transform it into a painting with extreme ease. It takes him less time to finish a painting, in which even the smallest grain of sand is depicted with accuracy, than one would ever imagine possible. On leaving I felt that I had undergone a session of yoga; a calm and a contemplative stillness only broken by the frenetic traffic of Kathmandu. When Rob goes for fieldwork he seeks out his vision in the surrounding reality. He looks for revelatory signs of a culture that talks of ages as well as of modernity, a thread that connects the present with the past by a meaning that is not lost, or a meaning that is lost but should not be forgotten. When he paints, his vision goes beyond the reality in front of him. The use of frontal perspective, the complete absence of anything else but a single subject, the absolute disembodiment of the themes he paints achieved by applying these simple concepts extract values that go beyond the physical existence (the reality) of his landscapes and monuments. His fluid and balanced style has been refined over the years to reach an extraordinary limpidity. Looking at his paintings, one sees his subject in a formal perfection. But what one sees is no mere depiction of an intriguing or special subject of dignified significance. His skill in the rendition of the subjects leads his work to a realism that is visionary, and which transcends into absolute abstraction. It is pure abstraction or rather a noumenon incarnated in the physical world. Painting subjects from the past does not make Rob a painter of the past. His modernity, in my view, rests in his almost metaphysical transformation of every "self" in front of him, be it a cave, a shrine to the local spirit, or a door decorated in distinctive Tibetan style, but, at the same time, keeping their physical presence intact by means of an almost extreme detail. Some of the words that Rob has recently written to describe Mustang apply quite vividly to his own work: "The chortens and temples enable the unseen to be seen and made accessible, transforming areas of the earth plane into sacred enclosures...". My wife is especially fond of a painting from a series he made before his work in Mustang in which an awkward facade, actually three facades in one, takes on a quality of pure abstraction. She asked Rob where this strange building was located. It is found in an area of Kathmandu were Buddhism and Hinduism have cohabited for centuries. Chabhel is famous for its stupa and for the temple of Mahakala, the "Great Black One", wrathful protector of Buddhism and Hinduism alike. We went to see it and, to her disappointment, the building was a pathetic little cement school, the product of random construction in an underdeveloped country. When he painted it, Rob extracted from the school an architectural idea that its builder could not possibly have imagined. This is a case in which he pushed his approach further. While he normally looks at signs in the surrounding reality, with the school Rob unearthed a noumenon as the treasure rediscoverers of Tibet (tertöns) did with the prophetic literature of "the Sect of the Ancients".(1) Rob has a summa divisio rerum of his work. He categorizes it into documentary and imaginary paintings. In my view this division is not always clear-cut. In some cases I am led to think that his documentary paintings are imaginary, while those that are imaginary seem documentary. His columns (see paintings 30 and 31 "Origin of the Corinthian Order in the Himalayas") are so imaginary that they look actual. A wall scorched by the winds stands solitary in an empty Mustang plain rather than in the mind of the painter. Some people say that Rob belongs to the tradition of eighteenth century painters such as the Daniells, who travelled to India to depict the colony's monuments.(2) I could not agree less. I distinctly remember as a boy of ten or so I used to spend hours with the books my aunt had given me, contemplating the paintings of the British artists of India. But I could not let my imagination run free, nor could I fly with the fantasy of a child to those monuments of that exotic and fabulous land. Those artists painted the monuments and a few scantily clad locals in strategic positions on the canvas. When I grew up, I understood that they also painted an invisible barrier separating their easel from the world around them. Rob's approach is different. He has overcome that barrier, although the subjects of his paintings are at first sight not so different from those of the colonial painters. He causes a building to levitate and takes it back on the sheet of paper, where it is painted. Rob looks at the land and its occupants, but he only paints sites and buildings. Yet his paintings tell of the people who inhabited them and their Culture, what these people thought and the events that have affected them. He favours painting walls rather than complete buildings, a choice that is intended to achieve metaphysical results. When the paintings show complete buildings, they are painted in a way that makes them pure structures. Rather than being close to the world of the Daniells, his work is like that of those painters of the Italian Trecento who felt compelled to abandon the hieratic world of saints and madonnas on a golden background, and to transfer them to the places where the rest of humanity actually lived. They did so by painting the monuments and landscapes around them with the same spirit, it seems to me, as with which Rob works and paints his own visionary monuments and landscapes. Rob's work breaks away from the colonialism represented, in my view, by the Daniells, and even by those contemporary artists who work on asian subjects, or on any culture to which they do not belong, with a mental barrier that leads them to depict their subject with a picturesque and exotic note. I think that many years ago Rob may have slid into a similar approach in some paintings. Now he consistently paints in a different way. It seems to me that he has gained a controlled understanding of the world he deals with. Rob's work is also the epitome of a non-bourgeois art. He does not paint the themes of everyday life and personal sentiments. He paints the centuries burnt in a minute, the greatness of giants of the mind unfolding every day in their abodes, the collective expressions of tribes and races. If this is classicism, then Rob is a classical painter. There is no shame in saying this in an epoch of "isms" and when art seeks to conform to commercial fashion. Rob takes a subject, not his own original creation, and paints it, leaving of himself an invisible imprint that is so strong as to pass, at first glance, almost unnoticed. He treats Mustang and the subjects he selects with extreme lightness, but the mark he leaves is indelible. Some anecdotes, ideas, and his vision of Mustang are the invisible traces left to me after our work together and the years of common interest in this land and other matters. Here are a few of them and a little information on Mustang. Into the barren land through Robert Powell's art Mustang is a stretch of rugged land with the unique feature that it provides a passage between the Tibetan plateau and the Himalayan foothills and thence to the tropical plains of India. It is possibly the most direct and easily negotiable corridor linking Central Asia and the Tibetan plateau with India, thus giving it a strategic pre-eminence throughout the centuries. Life in Mustang meant nomadic pastoralism and consequently trade. Whoever controlled Mustang controlled trade between the higher and lower lands. This trade guaranteed great prosperity to those who controlled it, as revenues were extraordinarily high. Internecine struggles among rival families of the same nomadic tribe secured the control of trade and guaranteed rich profits. In the trade between the nomad highlands and the farming lowlands leading to the Gangetic plain the biggest revenues earned by the nomads were from the taxes levied on salt along the route from Mustang to Mukhtinath. Trade on the route to Dolpo gave lower revenues. To this income one should add the earnings the nomads made by selling the products they received in exchange for salt - rice and various grains in the main - which they resold in the highlands for a large profit. Historical Mustang was forged by the nomads of the lands of Changthang to the north, where the territory opens up into huge, wild spaces, mainly steppe, significantly different from the dramatic, eroded and desert landscape of Mustang. These groups of Tibetan nomad pastoralists claim descent in deepest antiquity from nine mythical brothers who ruled the various regions of Tibet before the first king of Tibet descended from the sky on a scared mountain. They claim similar descent to that of the royal genealogy of the important region where Kailash, the sacred mountain, the axis mundi, is located. Their ancestor was the youngest of three brothers, the eldest being the forebear of the kings of the Kailash region. The youngest brother, riding a swift black horse and wearing a black robe, migrated eastwards to lands bordering the central regions of Tibet. His tribe was pushed back and, retracing its steps, came to occupy the lands of Changthang along the Tsangpo (Brahmaputra), just north of Mustang. The tribe broke into clans, one of which became the royal dynasty of Mustang in the late fourteenth century. Mustang is thus a land of nomads and its dynasty is that of the black-cloaked youngest brother who rides a black horse. The eroded, rugged nature of the land of Mustang, where the winds of the plateau blow and batter against some of the highest mountains on earth, is further ravaged by earthquakes. West Tibet, to which Mustang belongs, is a land of earthquakes and their occurrence is described in the ancient biographies of great spiritual masters as supernatural events foreseen by these teachers to the general incredulity of the people. I think that Rob has painted earthquakes when he shows us spectacular cliffs with tormented shapes. I like to remember here an account I found in a Tibetan text of a dreadful earthquake in 1505 that ravaged the Tibetan territory from Ladakh to the area north of Kathmandu. Only Mustang was spared thanks to the wisdom of the great master Jamyang Rinchen Gyaltshen, the son of the king of a neighbouring territory, who foresaw the event, cautioned the population and performed miracles to nullify the effects of the catastrophe. On the morning of the earthquake he told the population to leave their houses and stay in tents. When he saw his monastery blown in the sky like an open lotus, he stood still in meditation amidst the greatest havoc and, by the power of mental absorption into his protective deity, brought the massive building back to the ground intact.(3) No damage befell the lands along the Kali Gandaki. Nevertheless, some people died in the gorges of the river, trapped by the earthquake in the labyrinth of tunnels, caves, towers and passages the water had carved during aeons flowing downstream. * Mustang is a land of strategic forts. Its history is marked by forts from an antiquity as dark as a night without moon on the plateau. Mute ruins still dot its desert land, manmade structures that the elements have transformed into fantastic natural carvings. Rob's paintings turn them into disembodied tokens of a land which is itself a natural abstraction, a concept of the mind. Consider, for example, the earliest of these forts recorded in the works, the "Castle of the Dragoness", built in Mustang during the period of the ancient Zhangzhung kingdom. This kingdom had already acquired a mythical lore in the earliest documents that Tibetan literature has left to us. Its origin goes back to a time not recorded in the manuscripts and its collapse was masterminded by the Tibetans of the Central Regions in the mid seventh century. The Zhangzhung kingdom was defined by one network of castles in the heartlands and another in its vassal countries at the borders. Among those in the distant corners of the kingdom was the "Castle of the Dragoness". When Rob and I were in Mustang working together on its monuments, I often wondered about the kingdom and the castle. Memory of the "Castle of the Dragoness" is now as lost as is its location. One day, we were invited to the house of a village headman who asked me to read some old documents lying in the dusty library of his family. Most of them were traditional religious books and prayers of little interest, but one, composed of a few pages scribbled in a nervous cursive, attracted my attention. I attempted to read it aloud, translating it into some sort of English on the spot. The work opens with an apparently mythical description of the and of the kingdom known as Serib, where the "Castle of the Dragoness" was located. By reading it out loud I wished to show that the description was not so mythical because it corresponded precisely to the shape, the colours and the locations of the mountains around us, to the river flowing across the bottom of the valley. The landscape described could be seen from the village we were sitting in. I did not think that we had found the kingdom of Seth mentioned as early as the T'ang Annals (c. tenth century). The document was not old enough to be taken as authoritative, the evidence not so conclusive, and yet that made us redouble our efforts to understand the area which we already knew was important. This village can be seen in one of Rob's works, "The Passage through Tsuk". Ancient Chinese sources speak of as a kingdom with customs that are non-Tibetan.(4) Tibetans live in white cubic buildings that are often widely dispersed. In the Te Valley, which the old manuscript described as the kingdom of Serib, life is run in clustered multistorey buildings and the streets are narrower than outstretched arms. One can barely see the sky from these passages. They seem deserted because people live and socialise on the roofs, visiting each other across them. Life is lived above ground. We always felt that this enclave has little to do with its Tibetan surroundings. The walled town of Lo Manthang is laid down in the middle of a fertile plain where the green and pink patches of fields stand in bold contrast to the surrounding barrenness. Twin conical hills of different height stand to the north beyond the Lo Manthang river. On the summits are ruins of two castles. The higher one is the castle of the great Amepal, the most charismatic king of Mustang. He led fifteenth century Mustang with shrewdness and opportunism. Becoming a monk in old age did not prevent him from committing great treachery and indiscriminate assassination. On the other hill are the most extraordinary ruins of the castle of the queen. Rarely in Tibetan culture were buildings circular, and even more rarely were they elliptical. The castle is seen in a painting which I call "Queen Ellipse" that uses an aerial view which highlights the purity of its shape. It is an ellipse of rammed earth that spirals inwards, where the only inner structure is shaped like the fortress of a mandala. In this painting the aerial view is treated as if it was in frontal elevation. Seen from the sky, the castle becomes a most peculiar mandala, whose outer circle is opened and twisted. Beyond the white depression to the east of Lo Manthang, blinding under the huge sun of the Mustang altitudes, one sees far away through the rarefied air that dissects and flattens distances a considerable expanse of red and green. This is Tsoshar, the most northerly and remote area of Mustang. Adjoining it to the south is Shari, a Bönpo stronghold in east Mustang beyond the Kali Gandaki. A land of forts, Mustang is also a land of Bön, the non-Buddhist religion of Tibet. Based on ritual and a hermit life, Bön has often been treated with contempt by followers of Buddhism. Bön flourished in Zhangzhung. In the eleventh century, long after the demise of this ancient kingdom, ascetics of its oral tradition who meditated to attain "The Great Perfection" settled down in the cave-dotted cliffs of East Mustang. They came from the lands of Zhangzhung to the north. While making this simple statement, documents of Bön's own tradition record a war at an unspecified period, but probably around the late eleventh or early twelfth century. The war was caused by the presence of Bön in Mustang. These documents add that Bön had come there from the south.(5) This irreconcilable knot remains to be cut. Twisted ropes tied to trunks of wood are found in one of Rob's imaginary paintings. When I think about the diffusion of Bön to Mustang in the eleventh century, I see knotted ropes firmly tied around trunks of wood and I do not know how to cut them. Other paintings show subjects more manifestly influenced by Bönpo culture. * Rob went to Shari and Tsoshar a few times. He often told me how much he liked them. Of all the territories of Mustang, Tsoshar is the one closest to the wilderness of Changthang, Tibet's immense western plain. Tsoshar is set in grassy plains but with sedimentary cliffs, like the rest of Mustang, riddled with man-made cave complexes. Rob's paintings show how nature and humans conspire to make caves the most practical of dwellings. We also see how man and nature, in Tibetan culture, contrive to give us the most stunning combinations of natural architecture and architectural landscape. Tibetans have a sense for choosing the most wonderful spots in their awesome landscape, but without a violation of their spirit.(6) What we observe, and what Rob shows us, is man adding a bit of magic to these special places in a symbiosis that tells of the extent to which Tibetans studied the forces of nature and tried to master them. It is a commonplace that Buddhism is the main force in the culture of Tibet. This is surely so, but it adapted most skilfully to local cults. Tibetans recognised the fierceness and beauty of nature at the dawn of their civilization, and they came to respect, worship, and live with it, conscious that nature entrusted these places to them in the custody of impermanence. Rob paints the language man and nature invented together to communicate on the Tibetan plateau. The paintings of the shrines to the gods, the gates of the ancestors, the caves expanded and arranged by man in a complex system of floors, galleries and ladders, show that he too has come to understand the game between man and nature at these altitudes. I do not mean that he can recognize and call by name all the local deities and spirits that inhabit every corner of this desert land, as the mythical child with donkey ears could do in the days of proto-historic Tibet. But one can see in Rob's paintings the perfect balance between a patch of colour that man laid down in a cave and the colour that nature chose for the setting. Paintings of cliffs and caves use a different sense of perspective. He works in a more composite way, combining different viewpoints without abandoning the frontal one for some structures. The effects he achieves are particularly intriguing. * One must see the land of Mustang to understand the colours of his paintings. The land has stunning colours. Most of the landscape is a sandy brown. White in Mustang is rare and so blinding that it glows in the sunlight. Eroded mountains and nearby plains are red, blue, green and black in the boldest juxtaposition of colours. No place is possibly more dramatic in its contrasting colours than the area comprising Drakmar, Mathang Ringmo and Gemi. Here the landscape embodies an old Tibetan myth. The territories of the plateau are symbolised by a demoness. The demoness, which is Mustang, was slain in this area. She left traces of her blood at Drakmar, a valley all red with caves in its cliffs; her heart, pierced by a stupa, at Mathang Ringmo; her intestines as a wall of stones carved with mantras; her bile on the "Mountain of Turquoise", blue in colour, near Gemi. The blood she dripped all along Drakmar Valley is there in the "Blood of the Ogress" . When I see this painting I sometimes wonder whether this is the blood the rulers of the Mustang dynasty spilled when they slaughtered their nomad relatives on the way to becoming the undisputed lords of West Tibet. The literary accounts of Jiwakhar, the headquarters of the Mustang dynasty at the height of its power, give a history of cruel struggles in a cruel landscape. This power was based on the two principles of militarism and trade. When the other kingdoms of West Tibet, on which Mustang had an iron grip, decided to revolt and take a huge army to Mustang, they laid siege to Jiwakhar. The Mustangis resisted, and the siege came to nothing except to give rise to an insulting saying that the people of Lo Manthang could barely tolerate. The saying maliciously recalled the nauseating smell of Jiwakhar during the long siege because all the cattle of the Mustang rulers had died during it. It prompted a retort by the Lo Manthangpa. The next year, they summoned their nomad relatives from Changthang, who had been part of the anti-Mustang alliance, and, on the pretext of wishing to heal old sores peacefully, they killed, blinded, mutilated and imprisoned their chiefs.(7) The nomadic community of Changthang never recovered from this deadly blow. The ancient manuscripts recount how its survivors are found living a miserable existence of perpetual flight from the people of Mustang who wanted to finish them off. The ruins of Jiwakhar have still to be located and I would love to see Rob painting them. The colour palette used in the architecture of Mustang is definitely more garish and articulated than that found in most of the other regions of Tibet, which is generally more monochrome. Even the colourful Sakyapa architecture, so distinctive for its use of vertical white, red and blue stripes, has rather dull colours in Tibet. In Mustang, the buildings of this religious school often have more vibrant tonalities. Inspiration in the architecture of Mustang comes surely from the colours in the landscape. However, Ngari - the most westerly region of Tibet - is a country with erosion and colours similar to those of Mustang, but the shades used in the local architecture are far more subdued. Rob uses a more restrained palette than one finds in Mustang. His sobriety makes him opt for colours which are not too contrasting, sandy brown being the base of most of his work, often with different tonalities of red earth from Burnt Sienna to Venetian Red, and with patches of grey blue, sepia, light grey and yellow ochre. He collects the various types of earth with which colours are prepared in Mustang and uses them as standards for his choice of shades, but he is selective and only goes for more brilliant combinations of colours when the tonalities of the monument he is painting obliges him to do so. His use of white is conceptual. He does not paint it. White is that of the paper. This approach borders on the field of South and Central Asian linguistics, for he treats white in the same way as the vowel "a" is treated in many alphabets of these lands, Tibetan included; "a" is implicit and is not written. Rob's white is inherent and is obtained by painting the other colours. If his white is like the "a" vowel of some Asian languages, it is also like a Buddhist cave of central India in which architecture and sculpture have been carved by subtracting rather than adding. * Inside the walled town of Lo Manthang stands a three-storeyed temple, which is a symbol of the town. It was built in 1447-1448 at the instigation of the great master Ngorchen Kunga Sangpo, who came from Central Tibet to establish his teachings with the support of the royal family of Mustang. The temple would seem to have been the brainchild of the king Amepal, his wife and sons, but it is not. Its structure is perfectly balanced on the outside and seems to belong to a single building phase or a single architectural conception, and yet its interior denies this possibility. A huge throne on which sits the image of Jampa, the Future Buddha, the main statue of the complex, is so disproportionate as to dominate the whole of the ground floor. The statue of Jampa, however, occupies only the middle floor when it would normally occupy at least two floors of the structure. The third floor, which, in this kind of temple is usually reserved for the head of the colossal image of Jampa, is bare except for the surrounding murals. This decoration is appropriate for the type of "Paradise Rooms" on the top floor of many temples, but not for those dedicated to Jampa. Rob and 1, each studying the temple with a different approach, came to the same conclusion, that the Jampa Lhakhang must have undergone changes which sharply modified its original integrity. This state of affairs obliged me to research in the sources to clarify the enigmas that the Jampa Lhakhang of Lo Mangthang poses. Reading the biography of a famous Tibetan ascetic nicknamed the Madman of Tsang (Central Tibet), who lived an anticonformist and controversial life which ended in poisoning, I found a few interesting facts. Paying a visit to Lo Mangthang, the Madman of Tsang arrived at the court of the Mustang king at the time that some works in the town's main temple had been completed. He describes the murals which were just finished and they correspond to those still found today on the top floor of the temple.(8) The year of the visit was 1498, fifty years after Jampa Lhakhang was built. Knowing that Rob would like to have our suppositions confirmed, I went to see him at his studio. He had just finished painting some strange figures we had seen together on the third floor of the temple and which were part of the scenes described in the Madman's biography. There is something special about them that prompted Rob's painting for they are no longer even close to anything painted in the Tibetan tradition. They are black silhouettes in the unmistakable postures of the Dakinis, the fairies of the Himalayan traditions who walk in the sky (see painting 39 "Black Sun Dakinis"). Atmospheric agents have darkened their original colours dramatically. This reminds one of some murals in the caves of Dunhuang along the Silk Route, in which the depictions of suns have darkened in a similar manner. An invisible, inexplicable link seems to have connected these two sites so widely distant from each other. The peculiarity at the root of this painting is evoked by its title. The Thubchen Lhakhang is the other great temple of Lo Manthang, and its conception is quite different from the Jampa Lhakhang. Here, there is no question of a building extending vertically. It is rather a spacious single room with a forest of columns subdividing its interior on a regular grid. A huge platform against its west wall is where the statues of the temple gods are placed. Painted paradises from the late fifteenth century are on the walls. The use of pillars has a great significance in Tibetan architecture. Tibetans conceive and understand the dimension of inner space in terms of the number of pillars placed inside a monument. Thubchen had forty-two pillars and is thus a big temple. Intrigued by this forest of columns, Rob painted a work in which they are the pillars of space, and space in Thubchen Lhakhang is greatly emphasised by their presence (see painting 40 "Thubchen Lhakhang"). The painting reminds one of certain perspectives and vaults in the work of the great Italian master Piranesi, which was revolutionary for his time. The ambience of the Thubchen Lhakhang is surely less damned than those subjects etched by Piranesi. The inner space of a Buddhist temple in the Himalayas conveys different emotions to those evoked by the prisons of the Italian. Rob's use of light, descending from the roof as a luminous blade which hits the columns and the floor to bounce around diffusing itself softly in all direction, gives an effect of intense peace. Yet, the treatment of interior architecture is the same. A vision of eighth century Italy is transferred to fifteenth century Mustang and the experiment succeeds. * I have always been impressed by those representatives of the human species possessed by "a wonderful obsession": the dedication to a destiny people have chosen for themselves. Rob is one of those. I imagine that Rob, had he not become a painter, would have made a great Tibetologist but I suspect that this is not much of a compliment. In a time of superficial, fancy revivalism, his paintings talk on his behalf and treat with respect aspects of cultures which are dying or are already buried. Cultural diversity is facing extinction and he is one of those survivors who wishes to resist this creeping uniformity. Sometimes I wonder if the viewer of Rob's art can see the two unpainted doors in his work. The Door of the Sky is the emptiness of its pure abstraction. The Doors of the Earth are the caves, gates of the ancestors, eroded walls, the striped and white surfaces of the buildings, which come to inhabit the blank fields of his paper. Of old, Tibetans believed that to bring earth and sky together gave control of the mundane and divine planes combined, as far as the eye can see. But at what distance can one see the horizon in Mustang, the dominion of winds in a tormented landscape? The History of Mustang: a summary of events Judging by the great number of cave complexes sited on its bare and eroded cliffs, Mustang must have been inhabited by a substantial population since deepest antiquity. It is unclear who its ancient inhabitants were. Whether they belonged to the world of the Central Asian steppe or to cave dwellers of the Indian subcontinent is still a matter of dispute. The first sound historical reference to Mustang is found in the literature written in Tibetan and found in the cave-library of Dunhuang. The entry of the Tun-huang Annals for the rat year 652 records the submission of Mustang to the Yarlung dynasty which took control of the entirety of Tibet as well as huge tracts of Central Asia. It seems that Mustang remained under the same power until the ninth century but it is not certain whether this was continuous or not. In the tenth century it was under the control of the Ngari Korsum dynasty of West Tibet. The first indication of religious activity in the land dates from this period. Exponents of the Nyingmapa sect unearthed important literary treasures in the region. Bönpo meditators came to inhabit Mustang's caves in the following century, while it is unclear whether the diffusion of the New Tantras, spearheaded by the Ngari Korsum dynasty, found fertile ground here. The twelfth century saw the sedentarization of the Menshang nomadic tribe in the southernmost stretch of Tibet Changthang, bordering Mustang to the north. They would soon afterwards populate Mustang and establish their control there. In the first part of the thirteenth century Mustang came under Jumla. In the meantime groups of Kagyupa had settled locally in the footsteps of the great yogi-poet Milarepa, who, 150 years earlier, had frequented the expanse of lands to which Mustang belongs. A couple of decades later, Mustang was under the Tibetan kingdom of Gungthang, located to its north-east. The Gungthang kings were feudatories of Sakya, the seat of one of the religious schools of Tibet which involved itself in secular matters during that period. At that time - i.e. in the 1260s - Sakya surged to predominance over the whole of Tibet. Mustang was included in the administrative and military organization of Sakya. With the end of Sakyapa predominance a century later, Mustang returned to the control of the Menshang nomads. A branch of this tribe founded its dynasty and kingdom in the last part of the fourteenth century. With king Amepal, who exercised military control over the trade with the lower lands during the first half of the fifteenth century, Mustang became the main power in West Tibet. His son Agön Sangpo pursued the same aggressive policy as his father and increased the fortunes of his kingdom. His son Tashigön and his two brothers who ruled after the latter's death maintained the prosperity of Mustang at its peak. The fifteenth century was the period of greatest splendour for the land and was marked by the introduction of the Ngorpa religious system - a branch of the Sakyapa tradition - by the great master Ngorchen Kunga Sangpo. The fortunes of the Mustang dynasty started to decline in the sixteenth century. In the first half of this century, the crops from some lands of Mustang had to be paid to unidentified non-Tibetan people from the Himalayan hills, thus implying that Mustang had to concede some of its sovereignty and to pay tribute. Around the middle of the same century Mustang was hit by a famine, which enfeebled the kingdom further. A new scenario had taken shape in the meantime. Lower Mustang had passed under the sphere of influence of the kingdom of Jumla. Upper Mustang was helped by Ladakh to avoid domination by the powers of the lower hills. Internecine struggles occurred between the two territories of Mustang. By the late sixteenth century Jumla had taken the upper hand and extended its power over Mustang. In the following decades, the kings of Ladakh established themselves as the dominant rulers in West Tibet. This rise culminated with the conquest of Guge, one of the major kingdoms in this large expanse of lands, by the Ladakhi king Senge Namgyel. At that time Ladakh controlled most of West Tibet including Jumla. A campaign led Senge Namgyel and his warriors to the gates of Central Tibet. He stopped in Mustang on his way back to Ladakh and collected tribute, which shows that he had control over it. In this period the Drugpa subsect of the Kagyupa established itself in the territory. The Mustang king Samdrub Pelbar, who had been one of the major contributors to the Jampa Lhakhang in Lo Manthang, fought another war against Jumla around the mid-seventeenth century. The enmity between Upper and Lower Mustang remained the most characteristic feature of the scenario during the last part of the seventeenth century. The situation did not change much in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Renewed links were sanctioned by intermarriage between Mustang and Ladakh. It was then natural that the king of Ladakh came to the rescue of the king of Mustang who found himself involved in a skirmish in Lower Mustang against the local people who were supported by the warriors of Jumla. Some time later, Upper Mustang reached the lowest point in its political decline due also to the concomitant loss of power by Ladakh. Jumla and its Lower Mustang allies again exercised authority in the area. This situation changed when the Gorkhas from the Kathmandu Valley first took Mustang and then Jumla in the late eighteenth century. Some power was restored to Mustang when its king was recognised by the rulers of Kathmandu as a regional lord. Not immediately apparent at first glance, Mustang represented a great religious eclecticism. The Nyingmapa, Kagyupa, Sakyapa and Bönpo traditions have all put a foot in its territory. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- FOOTNOTES: 2 Thomas and William Daniell, the uncle and nephew team who journeyed to India between 1786 and 1794. (back) 3 The Biography of Jamyang Rinchen Gyaltshen: "In the same year he said: "This year, the surface of this land and of others will definitely be destroyed either by an earthquake or by heavy rains and had. Don't go to the top of the mountains. Don't stay in high buildings". Three months before the earthquake he gave advice to the king. He himself stayed in a single-storey house and in a tent... On the fifth day of the fifth month of the ox year (1505), at dawn, he seriously warned everyone: "Today, everybody has to leave the monastery. Whoever does not listen will pay a high price". So said he. He took his couch and went to the fields. Shortly after, the sky and earth turned upside down. A big earthquake shook the land five times. The monasteries, palaces and capitals of many kingdoms crumbled into ashes... As he said; "Phat, phat phat", his monastery, which was like an open lotus, returned to its pristine shape even though the lands had turned to dust ... His followers, the king, the patrons, monks and disciples were not affected by the events ... In the rocky gorges within eyesight, six men of the caravan in front, five men at the back, four donkeys and one dzo [female yak] died as rocks cracked and fell on them". (back) 4 Paul Pelliot ("Autour d'une traduction sanscrite du Tao tö king", translating from Fa yuan tchou fin): "Si-li is to the south-west of T'ou-fan (Tibet), and numbers 50,000 fires. Its villages are mainly along streams. The men throw a cloth over their heads. The women braid the hair and wear short skirts. The dead are left in the countryside. Mourning is in black and lasts for one year. Politically, the country is under Tibet". (back) 5 The Geneology of the Yangel clan: "The first Bönpo resident of' Tangye in East Mustang came from the lowlands. He was a disciple of the Lama from Dru (i.e. a place in the Himalayan hills south of Mustang). His name was Tongom Shigpo". (back) 6 The Biography of Ngari Panchen: "When he was sixteen, Ngari Panchen exhibited signs of his miraculous power such as meditating seated on the Lake of Drakmar ("Red Rock"), standing on the waters of Munnak ("Dark Forest"), flying like a bird to the Rock of Lhalung ("Divine Valley'), entering like a sparrow into the Bagamchen Cave ("Cave with a Dome"), running on the perpendicular surface of the Gowochen cave ("Cave in the Shape of a Head")". (back) 7 The Biography of Choleg: "As it happened that the Mustang king Agon Sangpo and the army chief Amogha told the Tsotsowa nomads: "There are many reasons why we and the Tsotsowas must hold talk,,. Come with your headmen to discuss them." Accordingly Tsotsowa Rigdzinburn led about ten headmen together with their assistants and went to Mustang. At that time Agon remained behind as he went to see the army chief. Agon's nephew, who was not far from the gathering place, went to the meeting. He said: "Is Jiwakhar's rotten smell still around?". As he knew that nothing good would ensue, Rigdzinbum was like a frog in a pot and no way out was left. Then, not many days after, as many butchers were each given a task, Rigdzinburn and his brother; Arpon, a chief from my own household; one called pön Gyel; five notables; and Rigdzinbum's minister Pelsi were murdered. Moreover, the eyes of five or six chiefs were taken out. At the same time, the Mustang troops killed a younger brother of Rigdzinbum, who came to rescue them from beyond the meeting between the people of Mustang and the Tsotsowas. The eyes of the elder cousin from the same nomad clan were put out". (back) 8 The Biography of the Madman of' Tsang. "The Madman of Tsang and his disciples went to Lo Manthang. He was welcomed with a sumptuous reception. He arrived in town when the works at the great Golden Temple of Mustang (i.e. the Jampa Lhakhang) had reached completion. One day, accompanied by Lodrö Gyaltshen, the supervisor of the artists, lie was shown the murals of the Buddhas of the Lands on the ground floor and of Dorjechang Surrounded by the EightyFour Mahasiddhas on the top floor, which truely was a paradise room. ...... (back) |