|

“What is the Tibetanness of this?” asked Tsering

Shakya in the opening roundtable, titled Traditions/Tensions: Contemporary

Art and Tibetan Society. “What makes this art Tibetan?” Shakya,

a renowned scholar of contemporary Tibetan history and literature at the

University of British Columbia, urged the panelists to engage with questions

of culture, history, identity, and especially tradition. There is, he

claimed, an internal community critique among Tibetans: “One is

disloyal if you don’t hold up tradition.” Given the occasional

redundancy of tradition, however, Tibetan society needs artists to push

past tradition, to reinvent expressions of Tibetan identity, and to speak

in a contemporary idiom. The artists, for the most part, agreed.

Fig.

1

Fig.

1 |

|

“We need to ask what art is,” offered Tsering

Nyandak, who paints in Lhasa as a member of the Gedun Choephel Artist

Guild. “Contemporary art is not necessarily a lineage of tradition.

. . . Artists don’t have to have the burden of tradition on your

back.” And yet, though some artists are able to work around tradition,

others see it as one of the demands of community, in which they are caught.

Dharamsala-based artist Sodhon spoke of the difficulty of painting to

fulfill his artistic needs, given “the duty of the artist to serve

[the] community.” And, one might add, to pay the bills. Sodhon is

a successful cartoonist, commercial and educational artist in the exile

community, who also makes oil paintings to, in his words, “breathe

new life into Tibetan culture.” As he explains it, Tibetan art “shows

the Tibetan mentality” and must be executed by Tibetans in order

to “contribute to a positive future.”

Artists at the symposium represented the far corners of

the global Tibetan community—two from Lhasa, two from the United

States, and one each from India, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Geographically diverse as this group was, there were nonetheless common

themes in their work, in the visions of these artists who had never met

or, in many instances, even communicated with one another before. The

“collective feel of this very personal art” was highlighted

by art historian Dina Bangdel. The persistent and shared references to

Buddhism in the exhibition works led her to follow Tsering Shakya’s

opening question by asking if it was “the recognizable Buddhist

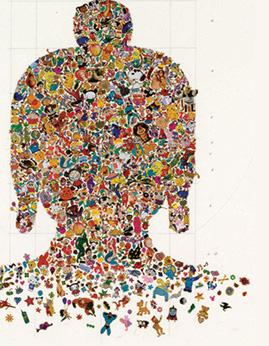

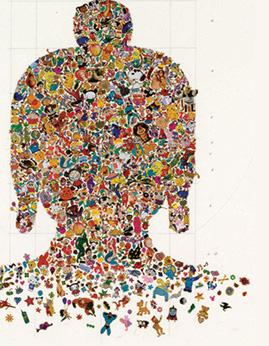

symbols that made this Tibetan art?” Gonkar Gyatso, who uses Buddhist

symbols and references overtly in his work, described this technique as,

in part, a search for his roots. Born in Tibet, trained in China, resident

in India for a decade, and currently residing in London, he is not so

much exploring a hybrid identity as searching for a “multisource

tradition.” “Tibetan culture is very heavy,” he observes.

“I am in some ways trying to reach people who don’t know Tibetan

culture. Mine is a serious message [delivered] through a playful method.”

|

Fig.

2

Fig.

2 |

The “Tibetanness” presented by many of the

artists is cultivated in a mix of spaces and places, some Tibetan, some

not. Kesang Lamdark speaks to this in his work: he is Tibetan by birth,

Swiss by citizenship, and trained in New York. His artistic sensibility

is indebted to some traditional Tibetan motifs, but he executes his work

in ways not limited to “Tibetan” styles or genres. Denver-based

artist Tenzin Rigdol spoke strongly to the absence, in his mind, of Tibetanness

in his work. “For me,” he said, “it is more about being

human than being Tibetan, . . . about investigating human relationships.”

He also claimed the elusive prerogative of the artist: “The beautiful

thing about art is breaking the definitions, making the art historians

scratch their heads.”

Definitions and interpretations will always be contested,

because culture itself is always contested. Anthropologist Charlene Makley

reinforced the idea of culture as a contested process of meaning making

during the roundtable Offerings: The Role of Art in Tibetan Culture and

Beyond. Tibetan society is more fractured than most at present; while

one community response has been to work to safeguard tradition, another,

albeit less heralded, response has been to create new traditions. As Losang

Gyatso explained, a key question in the Tibetan community at present is

the contested issue of “what to discard and what to keep.”

In his art, and (perhaps like all artists) in his life as well, Gyatso

addresses what happens when “things become symbolic rather than

meaningful,” and draws deep from a cultural repertoire of Buddhist

and pre-Buddhist images to explore what it means to be Tibetan.

The relationship of the personal to the collective, evident

in much of the art in the Waves exhibition, references the simultaneous

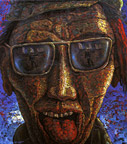

exploration of issues inside and outside the self. Lhasa artist Nortse

speaks directly to the relationship between Buddhist themes, contemporary

issues, and the place of the self in his works, exploring “materiality

and subjectivity.”

Fig.

3

Fig.

3 |

|

Our closing speaker, anthropologist Losang Rabgey, reminded

us that there are many “new and emergent sectors of Tibetan society.”

Art joins with these sectors to make and remake culture, to bring meaning

and symbols to life, to give hope, to pose questions, and to create the

future. The symposium audience was a diverse group, but included a large

number of Tibetans. They called for more women in the contemporary art

world as an important step toward meeting a key need as articulated by

Gonkar Gyatso: “There is no debate in Tibetan society,” he

said. “We need this. To push Tibetan art forward we need galleries,

curators, critics.” And also the participation, the support, and

the constructive criticism and engagement of Tibetans, male and female,

old and young, clergy and laity, in and out of Tibet.

The symposium ended on a note of excitement and anticipation:

We know that a new era of creative expression is being forged within a

rich traditional culture in transition. William S. Burroughs once said,

“Nothing exists until or unless it is observed. An artist is making

something exist by observing it. And his hope for other people is that

they will also make it exist by observing it. I call it ‘creative

observation.’ Creative viewing.” Contemporary Tibetan artists

watch the dissonant waves rippling across the lake of Tibetan civilization

today, and are imagining and creating ways to calm the lake’s surface;

they are observing certain futures into being. Together they—we—have

started the work of “creative observation.”

|