Articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

Download the PDF version of this article

An early Tibetan mandala of Ekallavira Achala in a private collection:

An Art Historical Analysis

September 09, 2013

text and photos © Pratapaditya Pal and image copyright holders

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Prologue

The history of portable Tibetan painting can now be confidently pushed back to the eleventh century. Buddhism was officially introduced to the country under the great ruler Song-tsen Gampo (r. 609-649) of the Yarlung dynasty and one can form a good idea of the architecture and sculpture of this early historical period [1]; but significant evidence for Tibetan painting of any kind, cannot be traced back much earlier than the tenth century.

Fig. 1Three main types of paintings are known in Tibet: murals or wall paintings existing mostly in temples and shrines in Western as well as South Central Tibet; pictures on cloth like the one being discussed here; and illuminations on manuscripts executed on paper. While the latter are diminutive in scale, cloth paintings can be of monumental size, as is the case here: 116 x 79 cm. (fig. 1) Traditionally, this type of painting is known as a thanka or thangka, a painting which can be rolled up. Generally, the Tibetans preferred to use linen or cotton imported from India as the support of the thangka rather than silk from China. Cotton or linen was the principal material used in India for painting and so the Tibetans adopted the practice just as the spiritual tradition was imported from the subcontinent. This particular thangka has cotton as its support.

As cotton is an organic material, it is possible to examine it scientifically. In this instance, the radiocarbon (C14) test has yielded a calibrated date between 1020 - 1160 CE with a probability of 95.4 %. [see Appendix A] Even if we accept the latest date, the mandala would be of the mid-twelfth century. As we will note below, a slightly earlier date may well be consistent with its stylistic features and can be corroborated by comparison with other early paintings. The surface of the thangka when originally found was considerably abraded, but fortunately most of the major passages escaped unharmed and the restoration has been carried out with sensitivity. Considering their age and the manner in which they were stored, such wear and tear are not unusual for thangkas painted with water-based colors. That they have survived as long at all is a miracle.

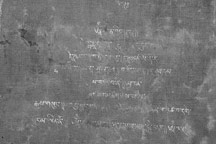

Fig. 2Painting a thangka is as much an act of faith for the patron and the painter as it is an aesthetic experience for the artist. There is an inscription in Tibetan script on the back of our thangka in red ink which is not easy to read (fig. 2). However it has been read and translated by Dr. Amy Heller and is reproduced in Appendix B. Unfortunately it contains no historical information but includes invocations and mantras in both Sanskrit and Tibetan language. The name of the deity is given as Chaṇḍamahāroshaṇa. It is possible that the man who is depicted at the bottom left hand corner, about whom more will be said presently, is the donor. Practitioners of thangka painting in Tibet can be both monks and lay persons, but there is no way to determine the artist responsible for this picture. While the majority of the artists working in the monasteries were Tibetan or Newars from Nepal, Indian artists may also have been present around the time this painting was executed. All one can say is that the artist responsible for the thangka was a master who has given us one of the finest examples of early Tibetan painting to have emerged so far.

Ye-shes-rgyal-mtshan, the teacher of the Eighth Dalai Lama (1758-1804) has characterized painters as "practitioners of dharma." Indeed, the long training of an artist is no less arduous than that of a monk. Sangs-rgyas-ye-she, the resident monk-artist of the present Dalai Lama in Dharmasala, teaches his students for nine years before certifying them. Three of those nine years are devoted to instruction in iconography and iconometry followed by a rigorous examination. "It is a mortal sin," says Sangs-rgyas-ye-shes, "to paint incorrectly, and the religious merit of painting correctly is endless," [2].

The subject matter of the painting relates it to Vajrayāna Buddhism. Vajrayāna, literally meaning the diamond or thunderbolt (vajra) vehicle (yāna) is the preferred designation for the last phase of Buddhism. It is also known as Tantra-yāna as it uses many tantric rituals involving mantra or incantations, images of deities and diagrams known as yantra and mandala, etc. to achieve the common Buddhist goal of enlightenment, voidness or nirvana. It is essentially a devotional path in which the practitioner uses the sculpted or painted image of a divinity as an aide memoire to enhance one's mental concentration, identify oneself with the nature of the divinity invoked and finally to empty one's mind of all traces of name and form that constitute the phenomenal world.

The Sanskrit word used to denote this practice is sādhana or, broadly, the effort to reach a goal, in this instance a spiritual goal. While the entire process can consist of complete and elaborate rituals and yogic and meditative practices expounded in substantial texts often composed by unknown religious masters of immense spiritual, intellectual and mystical powers, the artists usually use that portion of the sādhana known as a dhyāna (formula for mental visualization) as the verbal model for his image. Such dhyānas are found in anthologies or compendia such as Sādhanamālā or in works devoted specifically to particular deities. For instance, an independent text known as Ekallavīra Chaṇḍa Mahāroshaṇa-Tantra is devoted exclusively to the principal deity represented in this thangka. Such texts, originally composed in Sanskrit in India, were scrupulously translated into Tibetan and included in the canonical literature of Tibetan Buddhism.

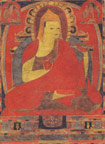

Fig. 3The name of the author of the Chaṇḍa Mahāroshaṇa tantra is unknown but we do have several sādhanas of this deity composed by other practitioners. The name of the deity is Chaṇḍa Mahāroshaṇa which literally means "the Great Furious Angry One." This is the designation used in the invocation in the inscription on the back of the thangka (see Appendix B). As may be seen from the title of the text, he is also characterized as Ekallavīra or "Sole or Singular Hero." An interesting explanation of the expression ekavīra or solitary hero is provided in a Tibetan source. The deity is characterized as an ekavira because he is a "widower". [3]. In other words, the deity should not be shown sexually embracing (yab-yum) the Prajña symbolized by the spouse. Eschewing what may be characterized as Left-Hand tantra (vāmatantra) Atisha Dipankara (982-1054 C.E.), who revived Buddhism in Tibet in the eleventh century, emphasized the solitary tutelary deity and composed a text called Ekavīra-sādhana-nāma (fig. 3). Yet another epithet that was attached to the deity is achala, literally meaning "immovable" or "unshakeable." This epithet is clearly a variation on akshobhya meaning imperturbable. It should be noted that Akshobhya is also a qualifier of the Buddha Shakyamuni whose resolve could not be shaken by the tempter Māra. The expression is used as the name of one of the five transcendental Buddhas who play so eminent a role in Vajrayana Buddhism as the heads of the five families (kula) to which all other deities belong. Appropriately, Achala belongs to the family of Akshobhya Buddha and assumes his dark or black complexion. However, in the inscription at the back the Buddha invoked is Sarvavid Vairochana (a cosmic form of the transcendental Buddha Vairochana) who may also be an emanator of Achala (see Appendix B).

It should be mentioned that the Hindu deity Shiva is often addressed as Sthāṇu or Pillar and by implication is immovable. Chaṇḍa and Prachaṇḍa are epithets of Shiva as well. Other commonalities with the Bhairava form of Shiva are the hairstyle with the orange-colored hair symbolizing the glow of fire, snakes as ornaments, and the tiger skin. It should be mentioned that these are as well common to the Vajrayana deity Mahākāla which is an ancient synonym of Shiva's wrathful manifestation. Rather than denoting direct borrowings, which was done mutually between Brahmanical (now designated "Hindu") and Buddhist religious praxis at many levels, these correspondences may reflect shared cultural ideas and values.

Judging by the surviving literature and art of the revival period of Tibetan Buddhism that began with the arrival in Tibet of the great Indian scholar and savant Atīsha Dīpankara Shrījñāna in 1041, it seems that Achala, as he is commonly known, was a very popular deity, especially with the Kadampa order which principally followed Atisha's teachings. One reason was the Indian master's personal preference for this deity [4].

Iconological Excursion

Typical of early thangkas, the composition consists of a large central field bordered on top and bottom with two narrow registers. Framed on either side by two ascending, meandering and flowering lotus vines is a wide red aureole which may have originally been energized by subtle, leaping tongues of flames now scarcely visible. The aureole attaches itself at the bottom to the further edge of the lotus with two rows of broad petals of variegated colors. On the red pericarp of the lotus, which symbolizes the human heart, are two prone figures looking up at the monumental black male figure who tramples them. They have no hand attributes and do not express any hostility towards their trampler. On the contrary, both seem to happily support Achala's feet.

Fig. 4The figure below the right leg is blue-complected and wears a stylized tiger skin like Achala (fig. 4). This together with the matted black hair may indicate that he represents a youthful Shiva even though he has no third eye or any other cognizant. Of a fair complexion, the other figure is distinguished by his elephant head with a pink trunk and may depict Gaṇapati or Gaṇesh. It should be noted that their divinity is emphasized by the halos behind their heads.

The principal deity Achala steps on the right in the militant posture known āliḍha and is also clad in a tigerskin that wraps his thighs like shorts. A snake forms his scared cord, he wears two serpent bracelets, and another pair of reptiles secure his orange, bouffant-like hair arrangement. Sporting a tiara, he is luxuriously adorned with jewelry. His right hand brandishes a sword and the left, held against the chest, displays the gesture of admonishment (tarjanīmudrā) with his index finger. It should be stressed that he does not hold the noose (pāsha) with this hand, as is generally prescribed in texts and seen in most representations of the god. There is, however, a textual passage where the noose seems to have been omitted as an attribute. This invocation of the deity was composed by Atīsha Dīpaṅkara who has already been mentioned. The text runs as follows:

Ārya Achala has a body dark blue in color with one face and two hands. The right hand holds aloft a sword and the left performs the wrathful gesture at the heart. Above a lotus and sun seat [he] stands with the right leg bent and the left straight [atop] Vighnarāja...Wearing a lower garment of tiger skin, having three eyes, red and round, orange hair flowing upward, all the limbs adorned with snakes, [he] stands in the middle of a blazing mass of fire. [5]

In her article on Achala, Amy Heller [6] quotes a second and longer description, also by Atīsha, which includes the noose in the left hand. The noose is absent from a much earlier description of Achala given in the Achala Tantra of c. 8th century preserved in the Tibetan canon. So there seems to have been some ambiguity regarding the inclusion of a noose and its absence in this painting is not an iconographical error. Moreover, noteworthy is the fact that the elephant-headed figure is called Vighnarāja, or king of obstacles, rather than Gaṇesh who is usually known as Vighnahartā, or remover of obstacles.

There are several interesting features about the various descriptions in Tibetan sources that are discussed by Heller that have relevance for our painting. In instructing the initiate, Atīsha says regarding Achala's form: "When constructing his excellent body from the realm of compassion (meditate thus): in the middle of the expanse of the blazing fire of wisdom, one head, two arms, brilliant dark blue body, two legs, one extended, the other contra ted, he crushes all great obstacles," [7]. Thus clearly there is room here for including more than one figure below Achala's feet rather than the solitary Vighnarāja found in most early representations (see fig. 7).

Indeed, two figures are also included in the Cleveland woven thangka of roughly the same date and have been identified as Shiva and Gaṇesh [8]. Moreover, according to the 8th century Mahāvairochanasūtra, where several descriptions of the deity are found, he is said to trample upon a yogin [9]. Thus, the blue figure here could represent a generic divine yogin, or specifically Shiva, who of course is the Yogin par excellence. The most unusual feature of this thangka and that in Cleveland is the presence of the ten companions around Achala who are engaged in aggressively destroying obstacles. These ten figures are not included in Atīsha's description but in another composed by Dharmakirti the pundit from Suvarṇadvīpa in S.E. Asia who was one of Atīsha's teachers [10].

Curiously neither Dharmakirti's nor Atīsha's sādhanas are included in the Sanskrit compendium called Sādhanamālā which contains four different sādhanas, all under the rubric Chaṇḍamahāroshaṇa. Only one of them is attributed to Prabhākarakirti. Since the suffix kirti is common to both him and Dharmakirti, perhaps they belonged to the same monastic order. All these forms however describe the deity in the genuflecting posture, popular in Nepal. So the upright posture seen in the early Tibetan representations as in this painting represents a different tradition popularized by Atīsha.

Articulately portrayed against the flaming background, the ten spirited figures contribute enormously to the central composition's liveliness (fig. 5). All have orange hair and are clad in tiger skins but with different complexions: dark blue, light blue and pale yellow. They also use diverse weapons, swords, a dagger, bow and arrow, spear, staff with skull (khaṭṭvāṅga) and two variant forms of mountains. The number ten clearly signifies the ten directions - eight quarters with the zenith and the nadir. Unlike their master who is belligerent but seems frozen in his dramatic posture from the dancer's repertoire, the acolytes are nimble and agile figures resolutely active in their energetic pursuit of adversaries.

The disposition of the nine emanations of the central deity in a circle clearly makes this a mandala of Achala. Eight such emanations are named in Ekallavīra-Chaṇḍa Mahāroshaṇa tantra [11]: Shvetāchala (White Achala), Pitāchala (Yellow Achala), Raktāchala (Red Achala), Shyāmāchala (Green Achala), Mohavajra, Paishunavajra, Rāgavajra and Irshāvajra. However, in the text meant for esoteric praxis each is said to be accompanied by a female companion called a "Vajrayogini" who are not individually identified. The central deity referred to as Krishṇāchala (Black Achala) is said to be embracing and kissing his partner who is named Dveshavajri. Thus, while Dvesha means Hatred or Enmity, the four male emanations are successively Delusion (Moha), Calumny or Malignity (Paishuna), Anger (Rāga) and Envy or Jealousy (Irshā). The date of this text is not known but notably no mandala of Achala is included in the Nishpaṇṇayogāvalī, a compendium of mandalas compiled by Abhayakāragupta, a contemporary of King Rāmapāla of the Pāla dynasty (1084-1130) and a professor of the Vikramshīla monastery from where Atisha left for Tibet in 1040 CE [12].

Fig. 5At the two upper corners of the aureole are two identically-colored Buddhas who can be differentiated by the gestures of their right hands (fig. 5). The Buddha near Achala's right hand is Akshobhya and the one across is Ratnasambhava. Directly below Akshobhya near the head of the supine blue deity below Achala's right foot is the portrait of a monk teacher distinguished by his brocade robe and a halo behind his head. Incidentally, it should be noted that none of the angry deities in the thangka including the principal figure is given a nimbus, as are all the others, even the two mortals and the trampled figures.

In the register above the central field are two more Buddhas wearing monk's garments at the two ends bracketing the group of the five transcendental Buddhas represented as bodhisatvas in their regal forms known as sambhogakāya, or body of bliss images. None is distinguished by their distinctive complexions and are uniformly yellow or golden as appropriate for "body of bliss" images. However the different hand gestures help to identify them individually. From left to right they are Ratnasambhava, Amitābha, Akshobhya, Vairochana and Amoghasiddhi. Akshobhya is directly above Achala's head as he is the head of the family, although Sarvavid Vairochana is invoked in the inscription on the back (appendix B).

Fig. 6Along the bottom register at the left is an elaborate scene of an adorant in lay attire but with a halo behind his head (Fig. 6). In front of him is a tall stand supporting a bound manuscript which acts as an altar with a stūpa and four other unrecognizable objects. Two stemmed bowls on the right of the stūpa have additional offerings and on the other side is a lamp. The tapering stem of the tall stand is flanked by a pair of conchshells on their metal supports and a red stemmed bowl with a pyramidal pile of grain. At the bottom is a golden lotus at the end of a sinuous stem with feet. Seated on a lotus, the officiant holds the thunderbolt (vajra) in his right hand and a bell (ghaṇtā) with his left, the two principal ritual implements in Vajrayāna worship. The exact identification of these two mortals would be crucial in determining a precise date for the painting (see Postscript below).

In five following panels are accommodated five more deities, beginning with a peaceful figure. His complexion and attributes identify him as Mañjushrī, the embodiment of wisdom. He is followed by yet another image of Achala, who, however, is not the slim figure represented above but is plump with a pot belly. The red figure in the next panel is the angry Hayagrīva with his distinctive horse's head lodged in his hair. The next figure is a three-headed and eight-armed form of Achala and the last of the group holding the chopper and the skull cup is most likely Mahākāla, another important protector deity of the Vajrayāna pantheon.

Fig. 7A final note on the various names and epithets of Achala. His proper name is Chaṇḍamahāroshaṇa, as mentioned earlier. There are various Sanskrit texts of different lengths describing this deity and the special esoteric rituals constructed around him [13]. In fact, the complete title of the text is Ekallavīra Chaṇḍamahāroshaṇa -tantra. Thus, here we encounter the first epithet of the deity which is ekallavira or "sole hero." This not only accounts for his heroic combative posture, that of a classical archer, but also his belligerent appearance and his slim, elegant form, or "excellent body," according to Atīsha. The text further provides the alternative name Kṛishṇāchala, meaning "the black immoveable one." Characterized as a vidyārāja, literally "king of knowledge," among his other names are Achala Mahābala and Achalanātha. Along with Trailokyavijaya, Achala is an important member of a class of deities classified by Linrothe [14] as Krodha Vighnāntaka, "the Angry remover of obstacles," both internal and external, that appear in the path of enlightenment.

Style and Aesthetic:

Fig. 8Apart from the calibrated date of 1020-1160 indicated by the technical examination, the painting can be dated with a fair amount of certainty on stylistic considerations. As it has been noted, the iconography and composition of this thangka is remarkably close to the Cleveland silk kesi thangka which cannot be dated after 1227. Other closely comparable examples are the well-known Green Tara in the Ford Collection (fig. 8) and the large Amitāyus thangka at the Los Angeles Museum of Art, both of which can be dated with some assurance to the fourth quarter of the 12th century. Thus, a late twelfth century date can be suggested for this Achala with confidence. But is it earlier?

Other than the ca. 1227 kesi Achala in Cleveland, two other early representations of the same deity may be mentioned here. One is a painted mandala in a private collection [15] which has been dated to ca. 1200 and the other is a small painting in the personal collection of Shelley and Donald Rubin, New York [16]. The former was perhaps the most iconographically elaborate mandala of Achala known until now and shows a combination of stylistic elements derived from Nepal and eastern India. In this thangka Achala is not a lissome figure but robust and potbellied like the form portrayed in the bottom row of our mandala without the outstretched Ganapati Vighararāja. Moreover, there are only four white miniature emanations of Achala prancing vigorously around the central figure of the smaller mandala.

By contrast, the Rubin Achala is a minimalist work as it portrays only the figure of Achala (Fig. 7). Kossak has cogently argued that the Rubin early Achala (only 35.6 x 17.1 cm) may well have been painted in eastern India and taken to Tibet sometime in the 11th or early 12th century. Its size makes it an ideal thangka for travel and likely it was painted somewhere in Bihar for either a Tibetan or an Indian monk. It is the closest stylistic model for the principal subject of our mandala, even though the god here tramples on only one obstacle, the elephant-headed figure, who, using his right arm as a pillow, lies on his side across the lotus base.

Indeed, these two early representations of Achala trampling on only a prone Vighnarāja may have easily been imports from India to which inscriptions were added in Tibetan, in the case of the mandala in the Lantsa script (om hum sarvavid) and a simple syllable in the Rubin Achala.

Compared to the two modestly sized as well as compositionally and stylistically simple thangkas, the more monumental Achala mandala has a more more elaborate composition, is more meticulously rendered with fine details and more resonantly colored. Noteworthy is the unusually narrow format of the Rubin Achala quite different from the proportions of the rectangular thangkas of early Tibet such as the Achala mandala or Ford Tara. I know of one other painting depicting the Bodhgaya temple with scenes from the life of the Buddha, certainly rendered in Bihar, which uses a similar long, narrow format. Thus the case for an Indian origin of the Rubin Achala must be kept in mind despite the syllable ram [17] in Tibetan script at the bottom which may have been added in Tibet as noted above.

Aesthetic Assessment

Aesthetically, this mandala of Achala is not only the most appealing of all early painted representations of the subject known so far, but it is also one of the most animated of all early Tibetan paintings, rendered in a style clearly related to that which prevailed in eastern India at the time. Most eastern Indian paintings on cloth have perished, as have the in situ murals at such monasteries as Nalanda, Vikramashila and elsewhere. However, since the same style was employed for murals, cloth or paṭa paintings and palm-leaf manuscript illuminations, which have survived in large numbers, one can easily form an idea of the style and aesthetics of the eastern Indian painting tradition. Apart from actual drawings, the Tibetans also used literary instructions included in texts such as the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa, translated into Tibetan in 1060, as models. For instance, the practice of including the portrait of the officiant in the lower left hand corner of the thangka is clearly described in the abovementioned text and also depicted frequently in eastern Indian sculptures [18].

As is usually the case in such religious paintings, the central area of the composition is occupied by the image of the principal deity surrounded (either in the field itself or in registers on the sides by miniature representations) by the retinue and related figures. They are all portrayed en face and with precise iconographic features. Any kind of ambiguity in their representation is unacceptable, as we noted above. The modeling of the figures is essentially linear but the nuanced and firmly drawn outlines and the adroit manipulation of colors in layered application provide the figures with a remarkable sense of volume, as is the case here.

The red fiery ground forms the second layer from which the dramatically striding figure of dark Achala springs forward as a rounded, animated form. The sense of real space is suggested by the receding plane of the lotus below, while the liveliness is further enhanced by the ten smaller figures that leap in all directions with enormous vivacity and energy. The sense of depth and animation are further augmented by the dynamic posture of Achala and the two active and articulately rendered figures he tramples below his feet. They are supposed to symbolize obstacles, but how graceful and gentle they are, unconcerned by their awkward situation. Both cheerfully serve as the god's footstools as does the dwarf in images of Shiva Natarāja, and support his feet with their arms. Both wear orange tiger-skin shorts and are bejeweled and haloed, as are Mañjushrī, the Buddhas and even the two mortal adorants. However, the angry divinities are without the honorific nimbus throughout the thangka. Especially noteworthy is the serene, beatific expression of the elegant blue figure below Achala's feet and the adoring gesture of his right hand. Clearly this is a battlefield, but the enemy is absent. Despite the mendacious attitude of the sword brandishing Achala with his red, rolling eyes and of his ten companions, there is no blood and gore or death and desolation in the visual narrative. Rather we are witnessing a tableau vivant of exuberant dancers on the stage of the human heart symbolized by the multi-colored lotus.

Realism in an earthly sense plays no part in the aesthetic of this art but naturalism does. In contrast to the theatricality (a pose struck on the stage by dancers when portraying a militant hero) of Achala, the two figures below his feet and the ten accompanying attendants are embodiments of natural movement and vitality. The figure of Achala conforms to ideal proportions but nevertheless it is not wanting in physical vigor and sensuousness.

What is especially engaging in these thangkas is the close attention to details, whether animals, organic forms such as the sinuous flowering vines that frame the aureole on two sides, or the luxuriant ornaments and articles of clothing. This is true of both the divine and the mortal figures, large or diminutive, at the top and bottom registers. Every item is minutely rendered with precision. Viewing these thangkas for the finesse of their rich details is time consuming but highly rewarding.

Finally, a few words about colors, which, as is the custom, are prepared from nature---either mineral or plant [19]. While the palette is limited to the primary colors - reds, blue, blueblack, yellow and white - they are employed with subtle tonal variations that rely on strong contrasts to create the required aesthetic effect. Red is the dominant color and is applied with saturated intensity and seductive charm. There is no arbitrary application of pigments and the purpose was to create a pattern of harmonious hues that both delight the heart and calm the mind.

We do not know the artist responsible for this extraordinary thangka but he was certainly a master of his craft. For clarity of narrative and action, for elegance of draftsmanship, for the dazzling effect of colors, this vivacious mandala of Achala remains a true masterpiece of early Tibetan portable painting.

Postscript

Since the above report was written several years ago, the Achala thangka has been published by Stephen Kossak in his study of early Tibetan thangkas [20]. Taking into account the technical (carbon dating), historical and stylistic evidence Kossak concludes that, "a Kadampa provenance of the picture is likely." He also posits that the painting was in all probability executed between 1063, when Dromton, the principal disciple of Atisha, died and the end of the century and suggests its possible association with the Retreng monastery.

Fig. 9Whether or not the mandala was commissioned in the Retreng monastery, it was likely executed after Dromton's death as will be shown below. Kossak identifies the monk seated above the person consecrating the thangka at the bottom left as "probably one of the 'Three Brothers', the principal disciples of Dromton." (See fig. 1) One reason for this identification is that he resembles a monk who flanks Atisha in a manuscript cover [21]. Be that as it may, what seems more plausible is that the second Tibetan at the bottom left (fig. 6) is clearly Dromton himself (cf. other portraits of Dromton [22]. In all these portraits his is a distinctive figure as he is always portrayed as an upāsaka or lay devotee who was never ordained (figs. 9 and 10). If indeed the officiant holding the bell and the thunderbolt is Dromton, the addition of the nimbus would confirm Kossak's conclusion that the mandala was painted after his death. However, Dromton's inclusion as the officiant would nevertheless suggest that the thangka commemorates an occasion when he consecrated a mandala of Achala.

Fig. 10Significantly the portrait of Dromton in the Ford Tārā (fig. 9) is the most distinctive and differs from the one in the Achala mandala (fig. 6) and another in a representation of two discoursing monks in a private collection, dated by Kossak to 1125- 1150 (fig. 10). In that case it would seem the dress and hairstyle given to Dromton in the Achala mandala was used as the model in subsequent representations of the loyal upāsaka disciple of Atisha and the real founder of the Kadampa order. Thus, since Dromton is represented as an active consecrator in the Achala thangka, its close association with him seems assured even if it was executed posthumously. That it was commissioned by a Tibetan patron (whether by an Indian or Newar artist) is clear from the use of the Tibetan script on the back even for the Sanskrit invocatory mantras rather than the Indian Vartula or the locally invented Lantsa scripts. Tibetan association is further evident from the shape and size of the bound manuscript wrapped in red linen that sits atop the tall stand supporting the stupa of Indian or Kadampa type. Indian or Nepali manuscripts of the period are written on palm leaf and hence are narrower and much lighter than Tibetan paper manuscripts. Indeed, this is a fine vignette of an active consecration scene with the diverse ritual objects rendered in realistic detail including the typical throne-back encountered in relief in Pāla period Buddhist sculptures.

Kossak further compares the Achala with the wellknown Ford Tārā (fig. 8) and the Kronos Amoghasiddhi painting [23], both of which may well have been executed by Indian artists working in Tibet. He also reaches this conclusion by extensive comparisons with Pāla manuscript illuminations, which, though diminutive in scale, reflect the style in which larger Indian paintings must have been rendered during the eleventh/twelfth centuries in such monasteries as Nalanda, Vikramashila, Kurkihar and others.

Fig. 11More exciting is a beautiful but fragmentary painting on cloth that depicts a dream of Atīsha which with greatest assurance can be regarded as an Indian work (fig. 11). This composition of Mañjushrī and Maitreya engaged in a tet-a-tet was first published in 1999 [24]. Elaborating on its stylistic characteristics, Kossak [25] convincingly argues for its Indian origin and then closely relates it to the Ford Tārā and the Achala under discussion. He concludes that "the iconography of Maitreya and Manjushri in discourse seems to provide clear evidence that it is a painting commissioned from India by Atisha to illustrate his dream."

If indeed the Tibetan account of the origin of the painting is true – and there is no reason why it should not be – then the logistics of the commission and where in India it was painted raise interesting issues. While Kossak subscribes to the view, along with some other scholars, that the fragmentary painting along with the Ford Tārā and Achala mandala were all painted by "eastern Indian artists," I would aver that the Divine Discourse prima facie was commissioned by Atisha from India, whereas the Tārā and the Achala mandala are products of Indian painters working in Tibet, or even Newar artists painting in a strongly Indian style. The smaller Rubin Achala painting (fig. 7) and the smaller mandala discussed above are likely to have traveled to Tibet from India (perhaps in Atisha's baggage?). It may be pointed out that even in its fragmentary condition the dimension of the Divine Discourse make it a larger thangka than the Ford Tārā and the Achala mandala.

Apart from texts such as the Mañjushrimulakalpa there is ample textual evidence in Sanskrit, Tibetan and Chinese that both murals and cloth painting were used by Buddhists in Indian monasteries. Fragments of murals have survived in Nalanda which were brought to light a few years ago. Atisha himself probably took rolled up cloth paintings, manuscripts and images with him on his journey to Tibet. We know that when he arrived in Guge he was greeted with a thangka portraying a multi-armed representation of Avalokiteshvara who, like Tārā, was one of his tutelary deities. We also know that after his vision of the Divine Discourse Atīsha is said to have ordered a painting of the subject to be made in India (a strange impulse with qualified artists locally available!). The new biography of the Master compiled by Ngawang Lama and revised by Lama Chimpa recounts the story of a dog who lived under the steps at Vikramashīla who upon his death was reborn as a human. He was a bhikshu or mendicant, an expert painter and a follower of the Atisha. He once requested a teacher called Vajrapāṇi, "Please tell me something about my own future." The mahāchārya (the great professor) replied, "You are in close touch with Dīpaṃkara [Atīsha]. Devote yourself fully to him. Paint as many portraits of Dīpaṃkara as you can." The unnamed artist is said to have painted about 70 portraits of the master and obtained great blessings. [26]. Could Atisha have suddenly wished to have his vision painted by his favorite artist in his distant homeland knowing that he would not return?

In conclusion, what is certain is that the Achala mandala is as great a masterpiece of the early thangka tradition to emerge from Tibet as the Ford Tārā. Indeed, its dynamic subject matter makes it a livelier and more dramatic composition. While the Tārā exudes the shānta or tranquil rasa or flavor, the Achala is a classic example of what would be the vīra or heroic emotion. Nevertheless, both probably reflect the visions of the great Indian Buddhist master Atīsha Dīpankara, though not as directly as the fragmentary but fortuitous representations of the Divine Discourse between Mañjushrī, the wisdom deity and Maitreya, the future Buddha.

# # #

[Since the above postscript was written in May 2013 I had the privilege of seeing a small polychromed wood carving of an Achala mandala in a private collection in Europe, probably of the thirteenth century. With minor variations it is remarkably close to the painted mandala the focus of this discussion. I have requested a scientific examination of the object and perhaps a post-post-script can be added to this article in the near future.]

Dr. Pratapaditya Pal Dr. Pratapaditya Pal is a world-renowned Asian art scholar. He was born in Bangladesh and grew up in Kolkata. He was educated at the universities of Calcutta and Cambridge (U.K.). In 1967, Dr. Pal moved to the U.S. and took a curatorial position as the 'Keeper of the Indian Collection' at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He has lived in the United States ever since. In 1970, he joined the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and worked there as the Senior Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art until retirement in 1995. He has also been Visiting Curator of Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art at the Art Institute of Chicago (1995–2003) and Fellow for Research at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (1995–2005). Dr. Pal was General Editor of Marg from 1993 to 2012. He has written over 70 books on Asian art, whose titles include, Art of the Himalayas: Treasures from Nepal and Tibet (1992), The Peaceful Liberators: Jain Art from India (1994) and The Arts of Kashmir (2008). A regular contributor to Asianart.com among other journals at the age of 85+, Dr. Pal has just published a biography of Coomaraswamy titled: Quest for Coomaraswamy: A Life in the Arts (2020).

REFERENCES

Bhattacharya, Benoytosh (ed.), 1949. Niṣpannayogāvali of Mahāpaṇḍita Abhayakāragupta. Baroda: Oriental Institute.

---., 1958. The Indian Buddhist Iconography (2nd Ed.), Calcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay.

---., (ed.) 1968. Sādhanamālā, 2 volumes, Baroda: Oriental Institute.

Chattopadhyaya, Alaka 1981 (1967) Atīśa and Tibet Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

Ge Wanzhang, 1996. "Learning to Paint Thankas," in On the Path to Void, ed. Pratapaditya Pal (Bombay: Marg Publications).

Heller, Amy, 1999. Tibetan Art: Tracing the Development of Spiritual Ideals and Art in Tibet, 600 – 2000 A.D. Milan: Jaca Books

---., 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe and Sorensen, 2001, pp. 207-208.

Kossak, Steven M., 2002. "Pala Painting and the Tibetan Variant of the Pala Style." The Tibet Journal, XXVII, 3 + 4, pp. 3-22.

---., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Kossak, Steven M. and Jane Casey Singer, 1998. Sacred Visions (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Linrothe, Rob, 1999. Ruthless Compassion (London: Serindia Publications).

Linrothe, Rob and Jeff Watt, 2004. Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond (New York: Rubin Museum of Art).

Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies).

Pal, Pratapaditya, 1984. Tibetan Paintings (Basel: Ravi Kumar).

---., 1990. Art of Tibet (Los Angeles: LACMA).

---., 1999 "Fragmentary Cloth Paintings from Early Pagan and their Relations with Indo- Tibetan Traditions," in Donald M. Stadtner (ed.) The Art of Burma: New Studies, Marg Publications, Mumbai 1999, pp. 79-88.

---., 2003. Himalayas: An Aesthetic Adventure (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago).

Rhie, Marylin M. and Robert A. F. Thurman 1999, Worlds of Transformation, (New York: Tibet House in association with the Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation).

Shastri, Mahamahopadhyaya Hara Prasad, 1917. A Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Government Collection, Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Tanaka, Kimiaki 2012. "The Mañjuśrimulakalpa and the Origins of Thangka," Asianart.com/ articles, pp. 1-6.

Watt, James C.Y. and Anne E. Wardwell, 1998. When Silk Was Gold (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Bhattacharya, Benoytosh (ed.), 1949. Niṣpannayogāvali of Mahāpaṇḍita Abhayakāragupta. Baroda: Oriental Institute.

---., 1958. The Indian Buddhist Iconography (2nd Ed.), Calcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay.

---., (ed.) 1968. Sādhanamālā, 2 volumes, Baroda: Oriental Institute.

Chattopadhyaya, Alaka 1981 (1967) Atīśa and Tibet Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

Ge Wanzhang, 1996. "Learning to Paint Thankas," in On the Path to Void, ed. Pratapaditya Pal (Bombay: Marg Publications).

Heller, Amy, 1999. Tibetan Art: Tracing the Development of Spiritual Ideals and Art in Tibet, 600 – 2000 A.D. Milan: Jaca Books

---., 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe and Sorensen, 2001, pp. 207-208.

Kossak, Steven M., 2002. "Pala Painting and the Tibetan Variant of the Pala Style." The Tibet Journal, XXVII, 3 + 4, pp. 3-22.

---., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Kossak, Steven M. and Jane Casey Singer, 1998. Sacred Visions (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Linrothe, Rob, 1999. Ruthless Compassion (London: Serindia Publications).

Linrothe, Rob and Jeff Watt, 2004. Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond (New York: Rubin Museum of Art).

Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies).

Pal, Pratapaditya, 1984. Tibetan Paintings (Basel: Ravi Kumar).

---., 1990. Art of Tibet (Los Angeles: LACMA).

---., 1999 "Fragmentary Cloth Paintings from Early Pagan and their Relations with Indo- Tibetan Traditions," in Donald M. Stadtner (ed.) The Art of Burma: New Studies, Marg Publications, Mumbai 1999, pp. 79-88.

---., 2003. Himalayas: An Aesthetic Adventure (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago).

Rhie, Marylin M. and Robert A. F. Thurman 1999, Worlds of Transformation, (New York: Tibet House in association with the Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation).

Shastri, Mahamahopadhyaya Hara Prasad, 1917. A Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Government Collection, Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Tanaka, Kimiaki 2012. "The Mañjuśrimulakalpa and the Origins of Thangka," Asianart.com/ articles, pp. 1-6.

Watt, James C.Y. and Anne E. Wardwell, 1998. When Silk Was Gold (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

I am grateful to many individuals for their help in the preparation of this article: Marco Pilati, Ferruccio Abiatti, Karl Debreczeny, Amy Heller, Ian Alsop for encouraging me to publish it in Asianart.com and Stephen Hotchkiss for his skills with the computer and editing.

Footnotes:

1. see Heller, Amy 1999. Tibetan Art: Tracing the Development of Spiritual Ideals and Art in Tibet, 600 - 2000 A.D. Milan: Jaca Books.

2. Ge Wanzhang, 1996. "Learning to Paint Thankas," in On the Path to Void, ed. Pratapaditya Pal (Bombay: Marg Publications).

3. Chattopadhyaya, Alaka 1981 (1967) Atīśa and Tibet Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, p.354. (see also, George, Christopher S., 1974, The Candamaharosana Tantra: A Critical Edition of the Original Text and English Translation of Chapters 1-8 (American Oriental Series, Volume 56))

4. see Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies), pp. 207-208.

5. Linrothe, Rob and Jeff Watt, 2004. Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond (New York: Rubin Museum of Art), p.281.

6. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe and Sorensen, 2001, pp. 207-208.

7. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies)., p.215.

8. Watt, James C.Y. and Anne E. Wardwell, 1998. When Silk Was Gold (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), no. 24, where the principal figure has been wrongly identified as Vighnāntaka.

9. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies)., p.217.

10. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies)., p.214.

11. Shastri, Mahamahopadhyaya Hara Prasad, 1917. A Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Government Collection, Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal., p.131.

12. Bhattacharya, Benoytosh (ed.), 1949. Niṣpannayogāvali of Mahāpaṇḍita Abhayakāragupta. Baroda: Oriental Institute, pp. 10-11.

13. see Shastri, Mahamahopadhyaya Hara Prasad, 1917. A Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Government Collection, Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal, pp. 131-142.

14. Linrothe, Rob, 1999. Ruthless Compassion (London: Serindia Publications), p. 151-156.

15. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies)., pp. 207-208, fig. 4; Kossak, Steven M. and Jane Casey Singer, 1998. Sacred Visions (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), no. 22.

16. see Linrothe, Rob and Jeff Watt, 2004. Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond (New York: Rubin Museum of Art), no. 37.

17. see Linrothe, Rob and Jeff Watt, 2004. Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond (New York: Rubin Museum of Art), p. 278.

18. See Tanaka, Kimiaki 2012. "The Mañjuśrimulakalpa and the Origins of Thangka," Asianart.com/ articles, pp. 1-6.

19. see Ge Wanzhang, 1996. "Learning to Paint Thankas," in On the Path to Void, ed. Pratapaditya Pal (Bombay: Marg Publications) and Bruce Gardner in Kossak, Steven M. and Jane Casey Singer, 1998. Sacred Visions New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), p. 193-197.

20. Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications. pp. 59-60, pl. 39

21. Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications, p. 43, fig. 25.

22. Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications, p. 25, fig. 12 and p. 72, figs. 46-47, p. 114, fig. 73.

23. see Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications, p. 25, fig. 12 and p. 32, fig. 17.

24. see Pal, Pratapaditya, 1999. "Fragmentary Cloth Paintings from Early Pagan and their Relations with Indo-Tibetan Traditions," in Donald M. Stadtner (ed.) The Art of Burma: New Studies, Marg Publications, Mumbai 1999, pp. 79-88.

25. Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications, 48-53.

26. Chattopadhyaya, Alaka 1981 (1967) Atīśa and Tibet Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, p. 430.

1. see Heller, Amy 1999. Tibetan Art: Tracing the Development of Spiritual Ideals and Art in Tibet, 600 - 2000 A.D. Milan: Jaca Books.

2. Ge Wanzhang, 1996. "Learning to Paint Thankas," in On the Path to Void, ed. Pratapaditya Pal (Bombay: Marg Publications).

3. Chattopadhyaya, Alaka 1981 (1967) Atīśa and Tibet Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, p.354. (see also, George, Christopher S., 1974, The Candamaharosana Tantra: A Critical Edition of the Original Text and English Translation of Chapters 1-8 (American Oriental Series, Volume 56))

4. see Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies), pp. 207-208.

5. Linrothe, Rob and Jeff Watt, 2004. Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond (New York: Rubin Museum of Art), p.281.

6. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe and Sorensen, 2001, pp. 207-208.

7. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies)., p.215.

8. Watt, James C.Y. and Anne E. Wardwell, 1998. When Silk Was Gold (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), no. 24, where the principal figure has been wrongly identified as Vighnāntaka.

9. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies)., p.217.

10. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies)., p.214.

11. Shastri, Mahamahopadhyaya Hara Prasad, 1917. A Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Government Collection, Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal., p.131.

12. Bhattacharya, Benoytosh (ed.), 1949. Niṣpannayogāvali of Mahāpaṇḍita Abhayakāragupta. Baroda: Oriental Institute, pp. 10-11.

13. see Shastri, Mahamahopadhyaya Hara Prasad, 1917. A Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Government Collection, Calcutta: The Asiatic Society of Bengal, pp. 131-142.

14. Linrothe, Rob, 1999. Ruthless Compassion (London: Serindia Publications), p. 151-156.

15. Heller, Amy, 2001. "On the Development of the Iconography of Achala and Vighnantaka in Tibet," in Linrothe, Rob and Henrick H. Sorensen 2001, Embodying Wisdom (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies)., pp. 207-208, fig. 4; Kossak, Steven M. and Jane Casey Singer, 1998. Sacred Visions (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), no. 22.

16. see Linrothe, Rob and Jeff Watt, 2004. Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond (New York: Rubin Museum of Art), no. 37.

17. see Linrothe, Rob and Jeff Watt, 2004. Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond (New York: Rubin Museum of Art), p. 278.

18. See Tanaka, Kimiaki 2012. "The Mañjuśrimulakalpa and the Origins of Thangka," Asianart.com/ articles, pp. 1-6.

19. see Ge Wanzhang, 1996. "Learning to Paint Thankas," in On the Path to Void, ed. Pratapaditya Pal (Bombay: Marg Publications) and Bruce Gardner in Kossak, Steven M. and Jane Casey Singer, 1998. Sacred Visions New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art), p. 193-197.

20. Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications. pp. 59-60, pl. 39

21. Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications, p. 43, fig. 25.

22. Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications, p. 25, fig. 12 and p. 72, figs. 46-47, p. 114, fig. 73.

23. see Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications, p. 25, fig. 12 and p. 32, fig. 17.

24. see Pal, Pratapaditya, 1999. "Fragmentary Cloth Paintings from Early Pagan and their Relations with Indo-Tibetan Traditions," in Donald M. Stadtner (ed.) The Art of Burma: New Studies, Marg Publications, Mumbai 1999, pp. 79-88.

25. Kossak, Steven M., 2010. Painted Images of Enlightenment: Early Tibetan Thankas, 1050-1450, Mumbai: Marg Publications, 48-53.

26. Chattopadhyaya, Alaka 1981 (1967) Atīśa and Tibet Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, p. 430.

text and photos © Pratapaditya Pal and image copyright holders

Download the PDF version of this article

Appendix A: C-14 dating | Appendix B: Inscription