asianart.com | articles

Articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

Download the PDF version of this article

The Ross-Coomaraswamy Bond

August 16, 2017

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

I would like to recall the names of four men who might have been present had they been living: Dr. Denman Ross, Dr. John Lodge, Dr. Lucien Scherman, and Professor James H. Woods; to all of whom I am indebted. The formation of the Indian collection in the Museum of Fine Arts [Boston] was almost wholly due to the initiative of Dr. Denman Ross… [1]

Fig. 1 Thus spoke Coomaraswamy at the dinner to celebrate his 70th birthday hosted by some of his close friends at the Harvard Club in Boston on August 22, 1947 (fig. 1). Eighteen days later on September 9, AKC would make his final departure, in his favourite garden of his house in Needham, Massachusetts, not far from the museum that had formed a bond between two men who introduced the new world to the arts of India. In no way was this less significant than the arrival of Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902) on American soil in the last decade of the 19th century [2].

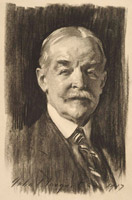

Fig. 2 I first heard the name Coomaraswamy when I joined the University of Calcutta (thank heavens the name of the university has not been changed to that of Kolkata in denial of history) in the late summer of 1956 as a graduate student of Ancient Indian History and Culture. The discovery of that name remained a seminal moment of my life. When I first encountered Coomaraswamy’s multivolume catalogue of the Boston Museum collections in the Calcutta University library as a student in 1956, I learnt that the great Indian collection for which the museum was famous at the time was identified as the hyphenated “Ross-Coomaraswamy Collection.” The “Ross” part of the moniker, however, remained a mystery until I came to occupy the position of Keeper of the Indian Collections in 1967 – exactly two decades after Coomaraswamy passed away. There is even a portrait of Denman Waldo Ross by no less an artist than John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) which I reproduce here, but I don’t remember ever seeing it hung anywhere on the walls of the museum (fig.2). It is worth repeating Ross’s comment on this portrait by Sargent, as recorded by Walter Muir Whitehill, “I have the greatest respect for Mr. Sargent. I am sure I look exactly like that, but I assure you I do not feel at all like that.” [3] Nor was Ross’s name mentioned often in the museum, though one retired curator was still around who had known him for a long time [4]. Soon after I joined my post I began an inventory of the vast Indian collection and realized that Ross was the single most popular name among all donors of Indian art, appearing frequently on wall labels of objects in almost all departments of the museum. Denman Ross was a globetrotter and a “global” art collector in the true sense of the word long before it became fashionable to ubiquitously use the expression, as is done today.

Before I begin the tale of the remarkable cooperation between the two men, a few words about the limited published sources that I have consulted for this remembrance. Not being able at my age to run from pillar to post in search of information (not available on the internet), I have had to depend on published sources to garner material about Ross. In his otherwise excellent and fulsome biography of Coomaraswamy, Roger Lipsey has little to say about the relationship between the two men as, according to him, a biography about Ross was being written at the time however, it is yet to appear [5]. Nevertheless, another has, which emphasizes Ross as the teacher of design at Harvard rather than as a collector, but it is still useful [6]. A warm assessment of Ross’s largesse to, and long association with, the Boston Museum is also included in Whitehill’s engaging centennial history of the museum [7]. Another useful source is, of course, sections of the privately printed tribute to Coomaraswamy by S. Durai Raja Singam to whom all Coomaraswamy addicts will remain forever grateful [8].

Notwithstanding bibliographical limitations, it is not difficult to reconstruct the historical relationship between the older patron and the younger curator who together formed what is referred to in Bengali as a manikjod, a pair of perfectly matched gems.

Denman Waldo Ross was born in 1853 in Cincinnati, Ohio to wealthy parents – John Ross and Frances Waldo – who moved soon after to Cambridge, Massachusetts to a large house at 24 Craigie Street where Denman lived until his death in London in 1935 [9]. He was thus 24 years older than Coomaraswamy. Ross graduated with honours in History in 1875 and earned his PhD in 1880 after submitting a thesis under the title of The Early History of Land-Holding among the Germans (published in 1883). As Whitehill writes, “ Such investigations were so little to his taste, however, that, after the death of his father in 1884, who had opposed his messing with art [italics mine], Ross abandoned history for good,” and, if I might add, took up “art history” [10]. Apart from his own innate inclination for “design,” he was inspired by that great founder of American art historical studies, the towering figure of Charles Eliot Norton (1827–1908) whose inaugural lecture, upon his appointment to Harvard, Ross attended. Even Norton would have been surprised, however, had he outlived Ross, to see that the seed he had unwittingly planted on a young receptive mind in his audience, had grown into a giant banyan tree whose roots and branches spread across the globe to satisfy Ross’s voracious appetite for art.

Commenting on Ross’s 1906 gift to the museum of 3,000 objects, Whitehill remarks: “Here again the variety was overwhelming, for there were sculptures, paintings, porcelains, pottery, and textiles from Japan and China, sculpture in stone and bronze from Cambodia, Siam [Thailand], Java and India; a series of drawings and paintings from Persia and India; a great variety of Coptic and Arabic textiles, as well as those from China and Japan, manuscripts; early printed books and book bindings representing the art of Europe” [11].

Fortunately Ross himself has left behind his “confession of faith” in collecting art in the 1913 issue of the MFA Bulletin, a short passage from which is quoted below not only to demonstrate “the unity of vision that inspired his collecting” but also why he would hit it off both with the Japanese savant Okakura Kakuzo (1862–1913), the first curator of Asiatic art at the museum (who was nearer his age) and, a couple of years later, with the younger AKC.

When I read this passage for the first time sometime in the 70s of the last century as I began my own serious engagement with art, I had made a note of it, and on rereading it today, I realize how significant it is for all collectors and historians of art. The last three sentences of the passage, and especially the aphoristic “The value of art does not lie in its own history, but in the higher life which it expresses and reveals to us”, would have particularly resonated with Coomaraswmay who too held similar views.It has not been intended [Ross wrote] in gathering this collection to illustrate the history of art or the ways of craftsmanship, though that is done incidentally. The history of art is indiscriminate. It chronicles both decadence and development. Our real interest lies in art itself as the expression of life. We want to know what life has been when it has been stirred and moved by the sense of beauty and the appreciation of what is best in the relativity of things, when it has risen above the struggle for existence and the sordid ways of business into the world of ideals, when it is concerned not so much with what it is but with what it ought to be. The value of art does not lie in its own history, but in the higher life which it expresses and reveals to us. We see in the masterpieces of art what life has been at its finest moments and what it ought to be again and again. It is for this reason that the study of art is one of the most important of all studies for everybody [12].

Fig. 3 Very little is known about the Ross-Okakura nexus or how they mutually influenced one another, and it would be a worthy subject for someone to explore. That they developed a close friendship during Okakura’s brief tenure at the museum is commemorated by a gift from Ross, which is one of the most outstanding examples of a stone sculpture from any culture in the collection. It is a magnificent limestone representation of the regally attired future Buddha Maitreya probably preaching in the Tushita heaven, carved ca. 530 CE during the Eastern (?) Wei period in China (fig. 3). Fortunately for us Whitehill has recorded the story of its journey to the museum, which he learnt from Kojiro Tomita, an appointee of Okakura and the curator of the Asiatic department from 1931 until 1963. I will let Whitehill tell the tale in his own words:

Who is to say that sacred statues don’t have minds of their own?From Mr. Tomita’s perceptive and capacious memory I learned only recently of a moving incident concerning the monumental statue that Denman Ross gave the museum in 1963 in memory of Okakura. Okakura himself had seen this sculpture in China in 1906 when it had been uncovered after many years of partial concealment in the Pai-ma ssu temple in Lo-yang. Having been greatly moved by it, he returned four years later to the White Horse Temple, only to find that it had disappeared. During the interval between these visits, the sculpture had been taken by a dealer to Paris, where Ross saw and bought it. So in the end, through Denman Ross’s unfailing instincts the statue came to the museum as a memorial to the man who had greatly loved it [13].

Fig. 4 Ross was a trustee of the museum, a titanic collector of art, including Indian, and a generous benefactor long before he and Coomaraswamy met. As an instance of his strong presence at the museum as trustee, in 1913 he was allowed to organize an exhibition from his own collection in the Renaissance Court (destroyed by 1970) that included a large selection of objects in diverse media from Europe, Egypt and Asia, which he had given the museum only in the previous year. This is also when he penned the long passage I quoted earlier outlining his philosophy of collecting. The exhibition comprised an astonishing variety of objects that included metal works from India, Cambodia, Thailand and Indonesia, as well as drawings and paintings from Persia and India. Indeed, the acquisition of the Goloubew Collection of Persian and Indian paintings in the following year by the museum was largely due to the encouragement of Ross [14]. I illustrate here a lively composition of an elegant dancing celestial nymph from Cambodia that was one of the objects displayed in the 1913 exhibition (fig. 4). One can easily see why such a bronze would appeal to Ross whose primary academic interest was to teach design.

Ross’s ideas of design have been thoroughly discussed by Marie Frank, but in passing it may be worth mentioning that here also his link with the MFA was significant. Two of the personalities with whom Ross interacted closely in the 1890s were Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) and Arthur Wesley Dow (1857–1922), both of whom worked in the department of Japanese Art at the MFA. Fenellosa had assumed the responsibility for the Japanese collections (including his own) in 1890 and later hired Dow as his assistant. As Frank writes, “The correspondence between Fenellosa, Dow, and Ross’s conceptions of design suggest how frequently they must have met and discussed art education… The pedagogies that Dow and Ross developed soon gained them national recognition” [15].

Undoubtedly Ross the collector also gained from this relationship with two pioneering experts in Japanese art as he did later from Okakura. In fact, as I read this chapter on Ross’s development as an art instructor, I thought of the similar situation that prevailed in India at the turn of the 20th century, especially in Calcutta (now Kolkata) with the two pioneering, “Brahmin” Tagore artist brothers –Gaganendranath (1867–1938) and Abanindranath (1871–1951). Both siblings, as well as Okakura and Coomaraswamy, were involved in that discourse and pedagogy [16].

When and where Ross and Coomaraswamy first met remains uncertain. Coomaraswamy’s biographer Roger Lipsey writes:

A different story is told by Adelia Ripley Hall who joined the museum in 1931 and worked with AKC for several years. In a tribute contributed to the volume published in 1974 by Singam she wrote:The diary of Dr. Denman W. Ross, the great patron of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, indicates that Coomaraswamy had let it be known that he was willing to sell his collection. Ross met Coomaraswamy, very likely probably during the concert tour [1916] and was immensely interested by his collection of paintings, of which Coomaraswamy may have had examples in the book Rajput Painting with illustrations drawn largely from the collection [17].

I am sure that this is more likely the truth for Ross was a frequent visitor to London and probably Coomaraswamy, who knew Goloubew well, was instrumental in persuading Ross to recommend the MFA’s acquisition of the Russian’s collection of Indian and Persian paintings, which had been on loan at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris. In fact, almost certainly Ross must also have facilitated Coomaraswamy’s concert tour to the States along with his wife Ratan Devi in 1916 during WWI. At least two letters have survived that make it clear that Coomaraswamy was having trouble in the UK getting his travel documents to visit the USA.Dr. Coomaraswamy had become acquainted with Dr. Denman Waldo Ross in London at the India Society (now the Royal Society of India, Pakistan, and Ceylon [now Sri Lanka]). Dr. Coomaraswamy had been a founder of the Society and a member of the original Executive Council. Dr. Ross was later an Honorary Vice President [18].

In a letter dated February 6, 1916 to Rothenstein he wrote: “I have had a very unpleasant experience in connection with our trip to America. I got a passport without difficulty in November [1915] and afterwards made all arrangements – a matter of no little expense, as you will imagine” [19]. However, it appears that he still required an additional permit from the Home Office, even after clearance from Scotland Yard for his passport, probably for entry into the United States. In the same letter he requested Rothenstein to intercede on his behalf with the Home Office, as he was due to leave in two days. In yet another letter to Rothenstein but undated (likely between November 1915 and February 6, 1916) he expresses his frustration and a possible cause for his difficulty:

Lipsey has nothing to say about the Cheltenham speech though he does write extensively about Coomaraswamy’s “nationalistic” activities and speeches in Sri Lanka, India and the UK in the first decade of the 20th century [20]. As to the “California seditionists” the reference is obviously to the Ghadar party that had been formed in California in 1913, and their fight for India’s independence [21].I am still harassed about the permit to leave, have spent several hours at Scotland Yard – the difficulty is due to words in a speech I made at Cheltenham in 1907! It is a bitter irony altogether. I fear I shall fail, but am to hear at 12:20 tomorrow. They fear I shall join the California seditionists who are in league with the Germans!

Finally, after overcoming the difficulties posed by British bureaucracy, Coomaraswamy and his wife Ratan Devi were allowed to leave and it was likely on that trip that AKC and Ross sealed the deal about the purchase of the former’s collection for the MFA. This was officially accomplished in the following year and the collection came to be known by the compound name: Ross-Coomaraswamy Collection. There can be no doubt that Coomaraswamy’s earlier publications –both volumes on drawings (1911) and Rajput Paintings (1916)– must have heped as published material always impress both collectors and trustees. Moreover, having already purchased the Goloubew Collection the board must have been receptive to expand the collection.

It is by now clear that without Denman Ross’s enthusiasm and initiative there would have been no significant collection of Indian art in the MFA and, more important, no Coomaraswamy as we know him. Whether or not he was the greatest curator in the history of the museum, he was certainly the preeminent “luminary,” as characterized by Meyer Schapiro (the renowned scholar of European art and a contemporary), the museum has had in its entire history.

According to Hall, “Dr. Coomaraswamy, having a private income, accepted the appointment at a token salary” [22]. As it is the salary for curators at the MFA was never generous, even when I was there from 1967–69. It was more like a gentleman’s club of prosperous New Englanders, as was evident from the private dining room where no women, either staff or eminent visitors, were admitted for meals. I remember being told that once when the distinguished archaeologist Professor Max Mallowan came to visit with his more famous spouse, Agatha Christie, he dined with the men in the private dining room, but she was taken to the general restaurant by Eleanor Sayre, the only female curator of the museum at the time. This happened probably around 1960; and even as I write this, for the first time, a woman candidate is close to the presidency.

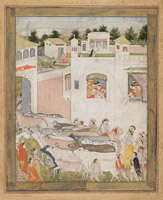

Fig. 5 In any event, Kojiro Tomita writes elsewhere that Coomaraswamy’s “appointment was renewed from year to year” [23]. So even if Coomaraswamy was financially comfortable when he joined I am sure his annual income from the museum or his accumulated capital was not quite enough – not to mention the uncertainty of the year-to-year renewal of his appointment – to live among the “Boston Brahmins” in the style he was accustomed to. Not only did he chase after investments in all sorts of commodities but he regularly sold art from his own vast collections to individuals and museums [24]. One of those individuals was no doubt Denman Ross until his death in 1935, though largely to augment the museum’s collection. At least one of the most well known Indian pictures in the museum is that known as The Hour of Cowdust (fig. 5). This painting that has now acquired legendary status is not part of the Ross-Coomaraswamy Collection but bears the credit line “Gift of Denman Ross” with the date of the gift as 1922. The picture certainly belonged to AKC when published first in 1916 [25].

Fig. 6 From the Ross-Coomaraswamy Collection I illustrate here, as a mere token, an extraordinarily powerful representation of the god Bhairava, the fierce aspect of Shiva, from the Basohli school (fig. 6). As is commonly known among aficionados of Rajput style paintings, the MFA excels in this particular school due largely to the RossCoomaraswamy bond.

Unfortunately, very little information is available regarding the mode of their cooperation; the biography of Ross that Lipsey suggested in the 70s was being written based on his diaries has not yet seen daylight. Had I been curious about the relationship when I served at MFA in the late 1960s, I could have found out more from some people who had known them both. Obviously they must have met frequently both socially and on museum business. Ross was an active, if not aggressive, trustee and came over to the museum often, visiting AKC in the back study of the Asiatic Department where Coomaraswamy had his desk, as will be discussed shortly. Of course in the 1920s both Ross and Coomaraswamy travelled abroad, though separately, for there is no record of their travelling together. Generally Coomaraswamy did the search and Ross financially helped with the acquisition, a symbiotic relationship characteristic of most American museums.

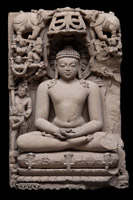

For instance, three of the objects I now illustrate here were given to the museum at different times but belonged to the Denman W. Ross Collection. Almost certainly, they were objects found by Coomaraswamy and acquired by Ross. The first is a splendid image of the goddess Durga triumphant over the buffalo titan, from the Pallava period (8th century), acquired in 1927 (fig. 7). Next in 1929 was added a deeply and richly carved sandstone relief with the meditating Mahavira, the founder of the Jain religion, from central India, filling an important gap in the collection (fig. 8). The third piece is an illustrated page of one of the earliest and most important Persian manuscripts of the 14th century (fig. 9). It is a leaf showing Alexander striking the dragon with a sword from the famous “Demotte” Shah Nama manuscript, the Persian epic composed by Firdausi. This particular illustration would have had a special resonance for Coomaraswamy for the myth is archetypal, going back to the oldest text in the world – the Sanskrit Rigveda of the second millennium BCE. There the slayer is the divine Indra and the dragon/serpent is called Vritra.

It should be noted that as Keeper of the Indian collection, AKC was also responsible for Islamic arts, as was the case when I followed in his footsteps two decades after his death in 1947.

In any event, in her recollection of her experience with AKC, Adelia Hall has described one occasion that is worth quoting:

Hall then goes on to state how sitting at her desk nearby she overheard the conversation between the unnamed dealer and Dr. Ross which was about the circumstances of Dr. John Lodge’s recent departure from the museum [27]. What is relevant for us is that Ross and the dealer were intimate enough for a bit of gossiping. The strong possibility is that the dealer was the young Nasli Heeramaneck who had arrived in New York in 1927 and by 1931 was well settled in his gallery in the city. Nasli had often told me how regularly he took the train to Boston to see both Ross (until his death in 1935) and Coomaraswamy. I have a feeling that the Mahavira sculpture (fig. 8) was an acquisition from Nasli.It hardly seems possible today that I should have met and have known the renowned and powerful Dr. Ross, when he was in his eighties. He often came to the “Back Study” to see Dr. Coomaraswamy and looked much the same as he did in the impeccable portrait sketched by John Singer Sargent only somewhat older and shaggy. However, he was still in the 1930s the great connoisseur, as alert and eager to discuss with Dr. Coomaraswamy the splendid object that may have come on the market. Jealous of his privileged position as a buyer of Asiatic art, he never wanted to miss obtaining the finest masterpieces for the museum. One afternoon in the autumn of 1931 Dr. Ross and a New York dealer came to the Department when the others were away from the office. They sat in the armchairs beside Dr. Coomaraswamy’s desk waiting for his return…[26].

Finally, this brief account of the Ross-Coomaraswamy nexus cannot be brought to a close without emphasizing that long before the two met Ross had already been seduced by the charms of Indian art – as is clear from the 1913 exhibition that he organized from his global collection. As has been noted, this exhibition included 151 Indian and Persian pictures that Ross had acquired from an unknown private collector, likely in Europe, and which he gave to the MFA in 1915 [28]. It was his interest in Indian art, along with Okakura’s affirmation in his first report to the trustees after his arrival at Boston, that led to the acquisition first of the Goloubew Collection of Indian and Islamic paintings in 1914 and then the Coomaraswamy Collection (along with the collector as Curator) three years later [29].

Fig. 10 The next landmark exhibition was in 1932, in nine galleries featuring another selection from the 11,000+ objects that Ross had given over half a century of his unflinching dedication to the MFA, as well as to the Fogg Art Museum (also a beneficiary of his largesse). This time it was the turn of the staff of the museum including his friend Ananda to organize the exhibition as an 80th birthday tribute to one of the most selfless benefactors that any museum in the modern world has had the privilege to possess. In that exhibition was included the alluring figure of a Yakshi from the Buddhist monument of Sanchi in central India (fig. 10). Notwithstanding its damaged condition, it is one of the most rare, evocative and iconic Indian sculptures that any museum can acquire. As Whitehill eloquently wrote in his centennial history of the museum: “With so remarkable a scholar as Ananda K. Coomaraswamy in charge, and with Denman Ross’s collecting at its normal pace, the possessions of this new section [Indian] multiplied like the loaves and fishes” [30].

I am sure had Coomaraswamy lived to read that sentence, he would have delighted in the biblical metaphor.

Whitehill further informs us that, after his sudden death on September 12, 1935 in London, Ross’s ashes returned to America enclosed appropriately in a Tang dynasty pottery jar provided by the art dealing firm of Yamanaka and Company, with which he had commercial association. Whitehill continues to remark, “Without him, the remainder of this history is bound to be duller” [31]. Hall adds that the jar was appropriate because Ross was a Buddhist, about which I am unable to add further light [32].

Ananda followed his friend twelve years later, also suddenly, and almost to the day, on September 9, 1947.

The following passage penned by Ross in the Bulletin of the Fogg Art Museum recollecting his travels in Asia beautifully sums up what he and AKC may have thought up together:

I must end this tribute to Ross by recounting one other episode that distinguished him from all other collectors. Over half a century of my professional career, it has always been my task as a curator to cajole donors for funds if I wanted to buy an object for the collection. With Ross it was the other way around.The beautiful is as you like it. Regarded as a reflector of colour in light, the work of art is good, bad or indifferent. Our aim was to select and to collect the best [33].

In 1931 the MFA acquired its most famous Chinese object – the scroll of the Emperors attributed to Yen-Li-pen of the 7th century – not because the staff wanted it but Ross did when he saw a reproduction of it in an exhibition catalogue in Tokyo in 1929. His lawyer, however, pointed out that as comfortably wealthy as he was, the price was prohibitive even for him. Ross, predictably, ignored him, made the necessary financial arrangements and the painting was acquired, –and as Whitehill stated only, “because of Denman Ross’s conviction that money was not important enough to save when it could be used for Chinese paintings” [34].

Such devotion and generosity are unknown today even when the American museum boards are made up of billionaires. Of Scottish origin, Denman Ross was indeed the most “lion-hearted” among a galaxy of munificent donors who made the museum’s department of “Asiatic” art renowned throughout the world for its collection.

Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

Dr. Pratapaditya Pal is a world-renowned Asian art scholar. He was born in Bangladesh and grew up in Kolkata. He was educated at the universities of Calcutta and Cambridge (U.K.). In 1967, Dr. Pal moved to the U.S. and took a curatorial position as the 'Keeper of the Indian Collection' at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He has lived in the United States ever since. In 1970, he joined the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and worked there as the Senior Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art until retirement in 1995. He has also been Visiting Curator of Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art at the Art Institute of Chicago (1995–2003) and Fellow for Research at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (1995–2005). Dr. Pal was General Editor of Marg from 1993 to 2012. He has written over 70 books on Asian art, whose titles include, Art of the Himalayas: Treasures from Nepal and Tibet (1992), The Peaceful Liberators: Jain Art from India (1994) and The Arts of Kashmir (2008). A regular contributor to Asianart.com among other journals at the age of 85+, Dr. Pal has just published a biography of Coomaraswamy titled: Quest for Coomaraswamy: A Life in the Arts (2020).

This article was written in the spring of 2016 as part of a new biography of AKC by the author, which now will be published in 2018 spring. The article is presented here to observe the 100th anniversary of Coomaraswamy’s arrival in America in 1917 though Ross should be credited as the first American to collect Indian art.

I thank Dr. Laura Weinstein, the Ananda Coomaraswamy Curator of Indian and Islamic Art at the MFA, Boston for facilitating the illustrations accompanying the article, to Ms. Rivka Israel for editing help, to Ms. Nancy Rivera my assistant, for her help with digital research and preparing the manuscript, and to Ian Alsop and Sameer Tuladhar of Asianart.com for their cheerful cooperation.

ENDTNOTES

- As quoted in Moore and Coomaraswamy 1988, p. 443. It should be pointed out that Ross’s first name is spelt Denham in this reprint and I am not sure why the error occurred, and have used the correct spelling in the quote.

- It may be worth enquiring if the swami and the “Boston Brahmin” met at all in Boston or at the Parliament of Religion in 1893.

- Whitehill 1970, p. 635.

- The curator who knew him was Dows Dunham, then retired Curator of Egyptian art who had joined the museum in 1914 even before AKC.

- Lipsey 1977, vol. 3, p. 96, fn. 3.

- Frank, Marie. 2011. Denman Ross and American Design Theory. A second new source for Ross is Reed 2017.

- Whitehill 1970.

- Singam 1974.

- The brief account of his life is based primarily on Frank 2011, Sizer 1943, and Whitehill 1970. It may be of interest to note as Marie Frank has discussed (pp. 20–21) Ross’s middle name “Waldo” derives from his mother’s family. The Waldo sisters [Francis and Mary who married John’s brother Mathew Denman (after whom our Ross was named)] were part of a large clan that included Ralph Waldo Emerson. It was the Waldo sisters who “sparked Ross’s interest in art.”

- Whitehill 1970, p. 137.

- Whitehill 1970, pp.138–139.

- As quoted in Whitehill 1970, pp. 139–140.

- Whitehill 1970, pp. 140–141.

- Hall (1974, p. 111) writes, “As Mr. J.P. Morgan did for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dr. Ross increased the Museum’s hold by leaps and bounds by adding entire collections brought together by some one else. He had acquired a collection of one hundred and fifty early Indian and Persian miniatures. He persuaded the museum to buy the famous collection of Victor Goloubew of one hundred and seventy-one Indian and Persian paintings which had been on loan at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris.” Undoubtedly, Coomaraswamy who knew Goloubew, was likely instrumental in encouraging that transaction, but I have been unable to trace the earlier collection of “one hundred and fifty early Indian and Persian miniatures” that Hall mentions. This is not the subsequent purchase of the AKC collection later in 1917.

- Frank 2011, p. 69 and especially pp. 68 for her discussion of the nexus among Ross, Tene Uosa, Dow and Albert H. Munsell in reforming art instruction in America.

- See Mitter 1994 and Pal 2015.

- Lipsey 1977, p. 126.

- Hall 1974, p. 111.

- Moore and Coomaraswamy 1988, pp. 326 and 327, for the following quote as well.

- Lipsey 1977, see index “nationalism.”

- For the Ghadar Party see www.lib.berkeley.edu. It may be mentioned that in 1916 Rabindranth Tagore too visited America via Japan and was a perceived target of the Ghadar Party in California for speaking out against unbridled “nationalism.” See Krishna Dutta and Andrew Robinson, Rabindranath Tagore The Myriad-Minded Man (New York: St. Martin’s Press), 1995, pp. 204–205. Interestingly on this trip, Tagore visited Boston and gave a number of lectures at Harvard but it is not known if Ross attended any of them and if they met at all. A search of Ross’s diaries may produce results.

- Hall 1974, p. 112.

- Singham 1974, p. 162.

- I was told by Dows Dunham how “Coomy” (as he was fondly called) would offer him and others in the private dining room stocks in mining companies in South America. Nasli Heeramaneck also told me of his purchases from AKC and I am sure a search in the registrar’s offices of many museums will yield interesting results. Currently an exhibition of painting and drawings acquired by the museum from Coomaraswamy are on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art, as I was recently informed by my friend Dr. Stan Czuma. Nevertheless, it should also be noted that he was a generous donor to the MFA and other museums. See Pal 2015.

- Indeed in the 1916 publication the painting is reproduced and credited to the author’s collection.

- Hall 1974, pp. 112 and 115.

- John Ellerton Lodge (1878–1942) was the Curator of the museum’s Asiatic department from 1915 until 1933. In 1921 he had concurrently been appointed the Director of the Freer Gallery at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC. Lodge, a son of the famous U.S. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, was thus a pucca “Boston Brahmin” and a close friend of both Ross and Coomaraswamy.

- The source of this information is Whitehill 1970, p. 362, repeated in Hall 1974. It would be a worthwhile project for an enterprising student to mine the Coomaraswamy catalogue and the museum’s archives and revisit the collection.

- As early as 1905 after his examination of the Asian collection Okakura had submitted a report to the trustees where he stressed that although the museum already had acquired an outstanding collection of Japanese art, it was now necessary to build up the Chinese and Indian collections and libraries. To that end he made a trip to India in 1912 to purchase art but due to health problems went back home to Japan and died the following year.

- Whitehill 1970, p. 368.

- Whitehill 1970, p. 442.

- Hall 1974, p.113. Unfortunately in her biography Frank (2011) says nothing of Ross’s personal faith.

- Whitehill 1970, p. 440.

- Whitehill 1970, p. 441.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fontein, Jan and Pratapaditya Pal. 1969. Museum of Fine Arts Boston Oriental Art, Tokyo: Kodansha.

Frank, Marie. 2011. Denman Ross and American Design Theory. Hanover & London: University Press of New England.

Hall, Ardelia Ripley. 1974. “The Keeper of the Indian Collection: An appreciation of Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy” in Singham 1974, pp. 106–124.

Lipsey, Roger. 1977. Coomarawamy: 3. His Life and Work, Bollinger Series LXXXIX. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mitter, Partha. 1994. Art and Nationalism in Colonial India 1850–1922. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moore, Alvin, Jr. and Rama Poonambalam Coomaraswamy. 1988. Selected Letters of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. Delhi: India Gandhi National Centre for the Arts and Oxford University Press.

Pal, Pratapaditya. 2015. In Pursuit of the Past: Collecting Old Art in Modern India circa 1875–1950. Mumbai: The Marg Foundation.

Reed, Christopher. 2017. Bachelor Japanists. New York, Columbia University Press.

Singam, Durai Raja. 1974. Ananda Coomaraswamy: Remembering and Remembering Again and Again. Kuala Lumpur: Privately Printed by the Author.

Sizer, Theeodore. 1946. “Denman Waldo Ross” in Dictionary of American Biography, edited by Allen Johnson, 21, Supplement 1, pp. 640–42. New York: Scribner.

Whitehill, Walter Muir. 1970. Museum of Fine Arts Boston: A Centennial History 2 vols. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

asianart.com | articles