asianart.com

| articles

REFERENCES

by Kabir Mansingh Heimsath

December 16, 2005

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

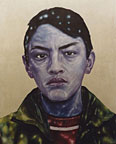

Tsewang Tashi, untitled no. 1 |

Not Artefact

In the western art world, the word ‘Tibetan’ has come to be directly associated with Buddhist scroll paintings – thangka – and statues, or else with antique furniture and carpets. These religious and traditional items have already made inroads into the lucrative Asian antiques market as well as the public museum culture of the US and Europe. [4The most recent exhibition perhaps being an antique furniture exhibition at the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, California, and it's accompanying catalogue (Kamansky 2004). The Rubin Museum, New York, devotes it's entire space to a permanent collection of Tibetan art, none of it produced since the 1950s.] In either case, Buddhist images or antique furniture, it is clear that the international aesthetic perception and monetary value of these objects is based on the same criteria – its authenticity as a cultural artefact. An ‘artefact’ contrasts with ‘art’ in the way that it is treated as the reflection of a particular set of cultural and religious values rather than the intentional expression of an individual. [5The exhibit 'ART/artefact' (Vogel 1988) prompted the question in my approach to Tibetan art. Although the exhibition and catalogue articles focus on African art and the aesthetics of dislocation and fragmentation, the false-dichotomy seems applicable to the Tibetan context. Nicholas Thomas (1997) connects the Durkheimian idea of social reflection to the treatment of artefact. I am taking my extremely broad characterization of 'art' from personal acquaintance and the discussion of theory by Victor Burgin (1986) especially.] Artefacts are typically relegated to primitive societies that are treated as social units in themselves (i.e. the pygmies do this, the Tibetans believe that) whereas art is produced in developed countries where people think and act for themselves (i.e. an Italian painted this, an American bought that). Since cubists and surrealists borrowed African masks for their own inquiries into aesthetics and beauty the dichotomy between artefact and art has become increasingly blurred in the art world, and indeed in most academic and cultural circles as well. But the idea of ‘Tibet’ has remained ensconced in some place far away from discussions that take place in the rest of contemporary cultural discourse, and any book or presentation of Tibetan art will automatically speak of tradition, religion and antiquity. [6See Harris (1999: chapter 1) and Moran (2004: chapter 6) on the importance of Buddhism in the cultural construction of 'Tibet'. The recent exhibition, 'Wooden Wonders' at the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, takes pains to point out when radio-carbon dating can prove that a piece of furniture is over 400 years old. Despite the title of the third edition of their beautiful book on Tibetan art (Rhie et al 1999), Robert Thurman again defies any suggestion that transformation may have continued after 1950 with quotes such as 'During its three modern centuries, from ca. 1650 to 1950, Tibetan civilization evolved to an unprecedented point where the enlightenment tradition's transformative orientation permeated the culture' (1999: 28). His implication of 'modern' and 'civilization' simply disregards any achievement that may have occurred in Tibet since then.] Without arguing the centrality of Buddhism in Tibetan culture, to assign authenticity and value based solely on historical validity is to relegate all so-called ‘Tibetan art’ to artefact, and to ignore its status as self-intentioned creations by individuals who think of themselves as artists. The insistence on a discourse which privileges the past, tradition, Buddhism, and cultural purity when looking at ‘Tibetan art’ relegates any discussion of such art to questions of authenticity based on cultural history rather than individual intention. [7James Clifford (1988: 217-235) explores the value of objects in relation to their historical relevance and cultural ethnographic authenticity. In two seminal essays, 'The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology' and 'Vogel's Net: Traps as Artworks and Artworks as Traps', Alfred Gell (1999) investigates the way in which the 'artefact' and 'art' dichotomy can and should breakdown with any serious and unbiased study of other cultures.]

Tempa Rabten, Palden Lhamo Tanka |

I suspect that the equation many foreigners make between Buddhism and Tibet leads us to seek evidence of traditional thangka elsewhere in contemporary painting, even if the painting itself has nothing to do with religious themes. However, as any tourist knows, thangka are widely available all over Lhasa and vary in quality from horrible manifestations of carelessness to incredibly fine works that would be hanging in a museum if they had the good fortune to be over fifty years old. Since the 1980s there has been a steady increase of indigenous demand for thangka, and a complementary increase in local production. Contrary to the supposedly informed view that all the thangka in Lhasa come from Nepal, the finest traditional paintings in Lhasa are either produced on order in Lhasa itself or come from the north eastern Tibetan area of Rebgong in Amdo.

Xiao Fei, a major retailer and wholesaler of thangka in Lhasa, is quick

to admit that much of his stock comes from Nepal, but they are the highest

volume and lowest quality pieces. He supplies thangka paintings to over

forty shops in Lhasa, catering to the upper stratum of the eighty or so

retail outlets city-wide ranging from street merchants to private dealers.

For comparison, on a short stroll down a popular tourist block and around

the main Barkor market place in September 2004 you could see the following

art retailers: about twenty-two souvenir shops selling ‘traditional’

items such as rugs, masks and prayer wheels; about nineteen shops selling

Buddhist thangka; about seven small retailers selling high-end antiques

(most of which are kept privately elsewhere), and exactly four stores

that sell modern paintings. Xiao Fei estimates about 60% of his retail

clients are Chinese and 40% are foreign, and it would be safe to use this

as a rough estimate of the general Lhasa market. Another group of his

local clients operate on lower-priced and pre-order basis, while most

of the local market for Tibetan thangkas goes directly to the supply studios

in Lhasa itself.

On the other side of the world, a walk around a couple small blocks in New York’s Greenwich Village reveals a similar scene with six shops advertising ‘Tibetan’ curios, thangka and antiques; almost all of the objects here are from Nepal and India and none of them displays contemporary-style paintings from Lhasa. This booming international trade in Tibetan artefacts deserves an extensive discussion in itself, but here it only needs to be noted that traditional Buddhist paintings dominate the market in Lhasa and New York. Contemporary painting is not the last vestige of a supposedly lost tradition, but rather a distinct new mode of art rising adjacent to a thriving world of religious paintings. [8Arjun Appadurai and Brian Spooner (1986) investigate the influence of international markets on local communities of production. As demand changes, so also do the patterns of production even in small, relatively isolated communities. George Marcus and Fred Myers (1995) continue these ideas with an emphasis on art, and the successful marketing of Aboriginal acrylic painting bears close comparison with the Tibetan situation, especially Steiner's article (1995) on the role of 'cultural brokers' in assigning value to indigenous art. Moran (2004: chapter 3) deals with the exotification and commodification of Buddhist identity in Kathmandu. My discussion with Xiao Fei indicates that he is well aware of what style thangka sells, for how much, to whom, and his orders translate directly to the producers.]

The projection of an artefactual mentality onto all things Tibetan helps the prosperity of objectified tradition; however, it also disregards the individual expression of contemporary artists.

Not Past

The history of contemporary Tibetan painting, it is generally agreed, begins with the iconoclast monk, scholar and itinerant intellectual Gedun Choephel (1903-51). The brilliance and restlessness of this poet-scholar has become almost iconic to young Tibetans everywhere; and for many intellectuals in Tibet his life serves as a real example of integrity and resistance. [9Luc Schaedler is working on a documentary film on the life and current legend of Gedun Choephel (www.angrymonk.ch). Tsering Shakya (2004: 66) discusses the way in which Gedun Choephel has been iconized amongst contemporary Tibetan writers although there does not seem to be a continuity between his writing and that of the later 'new literature' movement of post-Mao times. It is likely that his influence on art of the same period is even more tenuous, but his name is often extolled by contemporary artists.] Not many of Gedun Choephel’s paintings survive but from the few that do, and from random sketches and oral accounts, it is clear that he proposed not just a realist style but also an experimental one. Amdo Jampa (1916-2002) followed the progressive lead of Gedun Choephel and developed a photo-realist style for his overtly religious paintings. They were both interested in photography and the presentation of a personality rather than the idealization of certain qualities and formalized content that dominates traditional thangka painting. [10Harris (1999: 50-55) discusses the reception of photo-realist painting styles in exile and the use of photography as iconic portraiture (2003), Tsewang Tashi (lecture and discussion November 2005).] This shift towards portraiture rather than iconography is indicative of a more general modernist movement that was already taking place in Lhasa from the 1920s onwards. [11Harris and Shakya (2004) show the way in which Lhasa was transforming during the 1930-40s, in particular through interaction with the British consul and photography.]

Ling Gesar from Khandze school |

During the 1950s several established Tibetan artists went to inland China for study in art institutes that were based on western and soviet models. During the 1960s art-education turned into a complete training of new artists in the doctrine and aesthetics of socialism. As explained by the artist-teacher Tsewang Tashi, this mode encouraged the use of ‘red, bright, and light’ for important Party figures as well as the ‘three prominences’ formulated for the operas of Madame Mao: 1) the portrayals of positive characters, 2) the prominence of the heroic, and 3) the prominence of one hero in particular. [12Tsewang Tashi presented '20th Century Tibetan Painting' at the 2003 International Association for Tibetan Studies Conference in Oxford. Thanks to Paola Vanzo for providing a draft copy.] Discussions of realism in Tibetan art have rightly emphasised the imposition of social-realist style on Tibetan painters. [13Jamyang Norbu (1993), in one of his more subtle essays, comments on the cultural impact of communist art in Tibet, and Per Kvaerne (1994) echoes his sentiment of cultural degredation. Harris (1999: 151-162) provides an in-depth discussion of realism, socialist-realism, and thangka styles.] But both the colouring and formal attributes of socialist-realism are not far from those of Buddhist thangka painting and, ironic though it might be, there is no great aesthetic leap required to appropriate the religious iconographic mode for socialist propaganda (later paintings from Khandze illustrate religious themes in a dramatic style borrowed from socialist-realism). The painting of portraiture and landscapes, however, calls for individual analysis and close investigation rather than an idealized representation of form. The training of new artists during the 1960s involved a somewhat conflicting curriculum of graphic skills and philosophical indoctrination. So it is misleading to associate realism in contemporary Tibetan painting solely with the propagandist imperative of the Cultural Revolution period. Political, or religious, iconography does not encourage the same types of questions that the current generation of Tibetan painters are addressing in their work.

By the late 1970s Tibetan students were receiving art classes from middle school onwards, and more talented ones went to inland Chinese art institutes where they studied traditional Chinese watercolour as well as different Western styles of painting. The Tibet Artist’s Association was established in 1981; and, at its founding in 1985, Tibet University initiated a Fine Arts Department combining Western, Chinese and Tibetan styles of painting as well as international art history. A variety of artistic styles from Chinese ink-brush and Tibetan thangka to impressionism and abstract expressionism became validated and institutionalized during the 1980s. There continues to be a generously state-sponsored class of professional artists employed in the schools, university, and performing arts institutes of Tibet.

In Mainland China during the 1980s heady debates over liberal philosophical, political, and aesthetic ideas exploded into what one author has called ‘high culture fever’. [14Wang Jing's (1996) study is a brilliant critique of the myriad literary and artistic outbursts during the 1980s and early 1990s.] Perhaps riding this wave of progressive experimentation, several Chinese artists came to Tibet seeking a spirituality and authenticity they felt was missing from the rapidly transmorphing cities of eastern China. One such artist, Han Shuli, spent several years in Tibet and developed a kind of signature style blending dreamy semi-abstract forms with early Buddhist images. He exerted a tremendous influence on up and coming Tibetan artists during the 1980s and in many ways his approach has become associated with all contemporary Tibetan art; a recent Beijing exhibition of ‘Tibetan’ art featured him as the front-runner in their catalogue. [15Li (2004)] It does not seem coincidental that Han Shuli found his inspiration amongst the desolate ruins of Guge in western Tibet. This once powerful kingdom was mysteriously abandoned in the 14th century and epitomizes the Chinese and international fascination for a Tibet lost in the past. The fantastical architecture and frescoes of Guge were deserted and left to disintegrate through forces of wind and sand in a kind of naturalized form of historical determinism. Han Shuli and later Tibetan and Chinese artists have continued to be successful in selling this image of a wind-swept, pure, and fading Tibet on the international art market.

Penba Wangdu, Five Sins, no. 5 |

During the 1990s a group of artists, some self-taught and some trained

through the Chinese fine-art system of mixed traditional and modern media

were discouraged with what they saw as the growing institutionalization

and commercialization of contemporary art in Lhasa. Several unemployed

freelance artists were forced to produce facile copies of nomads, yaks,

and mountains in order to make a living selling works to tourists in search

of an ‘authentic’ Tibetan painting. If the form was not Buddhist

then tourists certainly wanted the content to be blatantly Tibetan. During

the late 1990s a few serious contemporary paintings were hung amongst

thangka and amateur tourist art in some of the newly opened art shops,

but interest was minimal and there was a clear dissonance between the

creativity of these artists and the expectations of the buyers. While

thangka were selling faster than supply, a single semi-abstract painting

would circulate from one store to another, show up in restaurants and

internet cafes, but refuse to be sold. At the same time, formally trained

students and teachers were frustrated with the propagation of historic

styles such as impressionism (or even thangka) that they felt were unrelated

to the questions and vitality of their current lives in Tibet.

Zhang Yung in front of New Life, Lhasa 2004. |

Image from Guge |

Gade, Lhasa 2004. |

Many of the contemporary painters in Lhasa wrestle with questions of tradition and change, but they do so with an agency that is entirely creative and innovative. It is telling that several artists in Lhasa adamantly oppose the priority of ethnicity in ‘Tibetan’ painting. One of the more successful painters, Gade, put it clearly during a recent conversation, "There was no question of Chinese or Tibetan [when forming the gallery cooperative]; it’s only afterwards that outsiders ask us about ethnicity. Chinese artists were included in Gedun Choephel from the beginning because they were part of the same group of friends and had the same ideas about art. " [20This and the following statements, unless otherwise referenced, are taken from extended interviews with the artists in September 2004. More general views are culled from personal conversations with different artists, gallery owners, and Lhasa residents during the past eight years. I am translating freely from Tibetan to English; 'gya-rig' in Tibetan translates literally as 'Chinese' but refers in particular to Han people and should not be confused with 'trong-guo', the Tibetan phonetic rendering of 'zhong-guo', China.]

At a recent talk given at the Sweet Tea House gallery in London, the French scholar Natalie Gyatso made the crucial point that, in contrast to discussions happening in exile, Tibetan artists in Tibet are not insecure about their identity. [21Natalie Gyatso (2004) spoke at Gongkar Gyatso's London gallery, The Sweet Tea House (www.sweetteahouse.co.uk)] Amongst most Tibetans I know in Lhasa there is an easy pride in their personal identity that does not seek overt legitimization through political ideology, oppression, or other external significations of ethnicity. This sentiment was voiced by several artists and is something that distinguishes the current atmosphere in Lhasa from the earlier ‘Sweet Tea House’ movement in the 1980s. Gade points out that the 1980s group discussed problems of politics and ethnicity, included a number of non-artists, and had only three exhibitions in local teashops. The Gedun Choephel group, on the other hand, was founded specifically to generate an interest in art for its own sake, includes only artists regardless of ethnicity, and keeps a full time gallery with rotating exhibitions.

Tserang Dhondrup, Lhasa 2004. |

Zhungde, Lhasa 2004. |

Wanggya, Li Zhibao and Lhaba Cering, Red Sun Over the Snow Mountain-Compassionate, Motivation, Expectation. |

A recent exhibition of ‘Contemporary Tibetan Painting’ in Beijing makes the point of featuring a number of Mainland Chinese artists alongside Tibetans from Lhasa and Shigatse. There is a large foldout reproduction of a realist thangka-style depiction of Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao painted by a cooperation of Han and Tibetan artists. Each chapter of the catalogue includes excellent reproductions and is introduced by a photo and brief biography that explicitly mentions the ethnicity of the featured painter. The inclusion of various ethnicities working together in creative arts speaks to a conscious effort to promote the plurality of a new China and is replicated through various publications and performing arts programs. When I asked Tsering Nyandak, an artist who has an affinity for especially dark colours and grotesquely smiling faces, about the Beijing catalogue, he said that he ‘didn’t really like it.’ In response to my hope that he might finally betray a latent ethnic priority he confessed that the catalogue designated a particular type of ‘rich colour painting on canvas’ as the ‘Tibetan Style’ and he did not want artists working in Lhasa to be confined to any particular mode of expression (incidentally one to which he clearly does not conform). Indeed, the characterization given in that catalogue should sound familiar to a western reader:

Therefore, contemporary Tibetan rich colour painting on canvas rises like rosy clouds over holy mountains and sacred lakes. It is the crystallization of the soul of Tibetan painters, featuring naturalness, freshness, and mysteriousness, which are unique to Tibet. [23Li (2004), introduction by Yu Jia written in Chinese, translator unknown.]

Nyandak is not opposed to Chinese paintings of Tibet, but reacts against any attempt to reduce the question of art in Tibet either to romantic spiritualism or ethnic identity. His painting ‘Bicycle’ is an almost demented portrayal of a man and woman playing while riding a bicycle. It has none of the cute naivety often projected on Tibetans by outsiders and explicitly subverts the image of happy nomads frolicking in the pasture. The exotification of minority cultures within the Chinese mainstream works as a double edged sword, at once promoting diversity within China while also confirming the rational, modern dominance of the Han Chinese. [24Dru Gladney (2004) is has been most insightful among several scholars to deal with this tendency in arts and literature especially. Various articles in Steven Harrell (1995) and his own monograph (2001) confirm the kind of ambivalent exotification at a more micro-level with ethnographic studies of different groups in Yunnan.]

Homi Bhabha is one of the most outspoken of post-colonial cultural critics to notice that, ‘An important feature of colonial discourse is its dependence on the concept of ‘fixity’ in the ideological construction of otherness’ (1994: 66). James Clifford borrows a similar concept that Arjun Appadurai calls ‘metonymic freezing’, and criticises ‘a process in which one part of aspect of peoples’ lives come to epitomized them as a whole, constituting their theoretical niche in an anthropological taxonomy’ (1997: 24). An earlier official publication from Beijing, Contemporary Tibetan Paintings (2001), reproduces several paintings from twelve different Tibetan artists (including prominent signatures in Tibetan script) and all the reproductions portray blatantly ‘Tibetan’ themes of monks, yaks, mountains and nomads even if other work by the same artist does not. There is an explicit recognition and resistance this type of ‘fixity’ in terms of both ethnicity and ‘traditional culture’ amongst artists in Lhasa today. The deployment as well as resistance to such epitomization is readily evident through many paintings emanating from Lhasa. The ever-prolific artist and teacher, Gade, overlays encrusted images of the Buddha (similar to Han Shuli’s) with somewhat comic characters from history, movies, or his active imagination (none of these comical contemporary images are included in his selections for the Contemporary Tibetan Paintings publication). Tsering Namgyal paints scenes that are overtly Buddhist, but does so with semi-abstracted structure and distorted figures taken from the world around him. His painting, ‘Memory’ contains oversized lotus flowers, monstrous sheep and a crooked monk lurching through a landscape packed with vibrant Van Gogh colours. Dedron says that she paints just ‘ordinary life in Tibet’, but it is with a diminutive exuberance inspired by Moghul miniatures from India. Jhamsang is one of the few trained thangka artists that has taken up contemporary styles; he combines exquisite technique with a picassoesque deconstruction of his own training. Likewise, the senior artist Tsering Dorje paints the Potala and monks, but with a heavy expressionist influence that warps the static and spiritual perspective in which these icons of Tibet are usually represented. [25The characterization of Tsering Dorje here is based on Natalie Gyatso's (2004) presentation.] All of these works illustrate a conscious manipulation of the ‘naturalness, freshness, and mysteriousness’ that are said to characterise Tibetan painters.

Jhamsang, in front of Wrong Positions, Lhasa 2004. |

Dedron |

Tsering Namgyal |

Zhang Dali, Chinese Offspring, (installation) Beijing 2004. (from Contemporary 72: 33) |

Indeed, several friends from Beijing have said that the new Tibetan art is too simple, or too traditional, to really be considered avant-garde or even original. [30Interviews with an art teacher, interested collector, and art dealer from Beijing currently working in Lhasa (September 2004).] The ‘Memory’ artist Tsering Namgyal, who had just returned from an exhibition in Beijing, laughed when asked about this and promptly moved his ashtray, cigarette and tea-cup into a mildly aesthetic arrangement and stated – ‘There, I say this has meaning and so it is installation art!’ He finds artists in Mainland China too self-absorbed with their own image and too enthralled by whatever proves fashionable at international exhibits. Several other Lhasa artists spoke disparagingly about a tendency to mimic anything that is hot in New York galleries and explicitly wanted to distance themselves from such trends. One afternoon Tserang Dhondrup was speaking of returning from time as artist-in-residence in New York and his attempt to utilize new styles, only to find them artificial. ‘It is not my life! It does not relate to this place, nor to most people.’ Gade agrees, ‘You can’t just go out and make an installation or video without some kind of background.’ Meanwhile Tsering Nyandak bemoans that, ‘There is no edge in Tibetan art,’ and that it is confined by traditionalist expectations. He has participated in some installation-performance projects and sees potential for the expression of ideas that may not translate as well to canvas. [31There was an environmental art performance, 'Living Water', which took place in Lhasa during 1996 but while the Beijing artist Song Dong's piece 'Printing on Water' has been exhibited internationally over a span of several years (Asia Society, New York), the Tibetan artists that took part have not been publicized (Tsering Nyandak and Tsewang Tashi, personal communication). Gongkar Gyatso, now in London (www.sweetteahouse.co.uk), has successfully incorporated conceptual and installation pieces into his impressive body of work and has recently been increasing connections with artists still in Lhasa.] But Gade insists that ‘concepts’ can be illustrated through painting as well as they can through installations or videos. Tserang Dhondrup reminds us that cultivating the kind of atmosphere that allows for change and creativity is exactly what they are trying to do. Gade laughs and says, ‘Yes, we want to change, but foreigners wants us to stay still!’ Again, all these artists explicitly counter the cultural ‘freezing’ that Appadurai, Bhabha, or Clifford critique in colonial discourse; a discourse that still haunts international as well as Chinese representations of Tibet and its art.

Conclusions

Dedron, (not yet titled) |

One evening, as foreigners are wont to do, I was pushing my own interest in Tibetan ‘space’ and advocated experimentation with installations when one artist sarcastically pointed out that they were almost done building a massive piece with two iron rails right across the northern landscape of Tibet. ‘Perhaps I could use that as my “installation”?’ He was referring to the new Qinghai-Lhasa railway due to be completed in 2006 and projected to bring in enough people and money to double the current size of Lhasa. It is clear that these artists are living in a dynamic space peculiar to Tibet and they grapple with it every day and in every painting. It is also clear that these artists are not naïve in their diffidence towards the latest fashions. They are self-conscious and actively engaged with their current Tibetan-ness, not faded remnants of a culture lost in the past. Although we, the foreign audience, play no small role in success or failure of Tibetan art as critics and clients, it is ultimately the artists themselves who will present Tibet as they see fit.

The tensions between traditional and contemporary, between Tibet and

the rest of the world, between individual and society, or the artist’s

vision and the audience’s expectation pervade the discussion of

art in Lhasa. But these are dynamics that are important for any artist,

anywhere. I have tried to show that ‘tradition’ in the current

Tibetan artistic context is not a deterministic force but something that

is self-consciously addressed by each artist. I also contend that contemporary

art in Tibet has to do with a much wider field than thangka painting and

it should be considered independently of that specific tradition. There

is an overt effort on the part of artists in Lhasa to break down the norms

and expectations both of the western art world as well as the western

Tibetophile world that ignores their paintings. I am convinced that certain

artists in Lhasa are conceptually far ahead of any scholarly representations

of Tibet published thus far, and that we students of Tibetan culture have

much to learn from those who spend their life thinking about how to present

themselves on canvas. Our own responsibility is only to look, and hopefully

in some small way, to see.

| © Kabir Mansingh Heimsath |

Notes: 1. A recent exhibition at Tibet House in New York, ‘Old Soul New Art: A Premier Exhibition of Contemporary Tibetan Artists’ (25 February – 17 June 2005) was a landmark exhibition of three Tibetan artists living in England, Australia, and the USA. ‘Visions from Tibet: a Brief Survey of Contemporary Painting’, organized by Rossi and Rossi and The Sweet Tea House galleries in London and Peaceful Wind gallery, Santa Fe in October-November 2005 was the first international exhibition and catalogue of artists from Tibet itself. 2. Dodin and Rather (2001) include several articles on the perceptions and mis-perceptions of Tibet and its people by outsiders. Clare Harris’ pioneering book on Tibetan painting (1999) is one of a few, but growing number, of exceptions to this over-general but largely still-applicable characterization. Her treatment of post-1950s Tibetan art is reflexive and concerned with the contested ‘authenticity’ of things Tibetan. Peter Moran’s (2004) close study of the interaction between Tibetans and Westerners in Kathmandu also investigates questions of mediated authenticity and has been central to the formulation of my own brief investigation. 3. The growing discussion on the parallel interests of art and anthropology (Scheider 1996, Marcus and Myers 1995, Clifford 1997) has also influenced my perspective in this article. Johannes Fabian’s discussion of allochronic discourse and the objectification of the ‘other’ is especially relevant to my arguments. 4. The most recent exhibition perhaps being an antique furniture exhibition at the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, California, and it’s accompanying catalogue (Kamansky 2004). The Rubin Museum, New York, devotes it’s entire space to a permanent collection of Tibetan art, none of it produced since the 1950s. 5. The exhibit ‘ART/artefact’ (Vogel 1988) prompted the question in my approach to Tibetan art. Although the exhibition and catalogue articles focus on African art and the aesthetics of dislocation and fragmentation, the false-dichotomy seems applicable to the Tibetan context. Nicholas Thomas (1997) connects the Durkheimian idea of social reflection to the treatment of artefact. I am taking my extremely broad characterization of ‘art’ from personal acquaintance and the discussion of theory by Victor Burgin (1986) especially. 6. See Harris (1999: chapter 1) and Moran (2004: chapter 6) on the importance of Buddhism in the cultural construction of ‘Tibet’. The recent exhibition, ‘Wooden Wonders’ at the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, takes pains to point out when radio-carbon dating can prove that a piece of furniture is over 400 years old. Despite the title of the third edition of their beautiful book on Tibetan art (Rhie et al 1999), Robert Thurman again defies any suggestion that transformation may have continued after 1950 with quotes such as ‘During its three modern centuries, from ca. 1650 to 1950, Tibetan civilization evolved to an unprecedented point where the enlightenment tradition’s transformative orientation permeated the culture’ (1999: 28). His implication of ‘modern’ and ‘civilization’ simply disregards any achievement that may have occurred in Tibet since then. 7. James Clifford (1988: 217-235) explores the value of objects in relation to their historical relevance and cultural ethnographic authenticity. In two seminal essays, ‘The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology’ and ‘Vogel’s Net: Traps as Artworks and Artworks as Traps’, Alfred Gell (1999) investigates the way in which the ‘artefact’ and ‘art’ dichotomy can and should breakdown with any serious and unbiased study of other cultures. 8. Arjun Appadurai and Brian Spooner (1986) investigate the influence of international markets on local communities of production. As demand changes, so also do the patterns of production even in small, relatively isolated communities. George Marcus and Fred Myers (1995) continue these ideas with an emphasis on art, and the successful marketing of Aboriginal acrylic painting bears close comparison with the Tibetan situation, especially Steiner’s article (1995) on the role of ‘cultural brokers’ in assigning value to indigenous art. Moran (2004: chapter 3) deals with the exotification and commodification of Buddhist identity in Kathmandu. My discussion with Xiao Fei indicates that he is well aware of what style thangka sells, for how much, to whom, and his orders translate directly to the producers. 9. Luc Schaedler is working on a documentary film on the life and current legend of Gedun Choephel <www.angrymonk.ch>. Tsering Shakya (2004: 66) discusses the way in which Gedun Choephel has been iconized amongst contemporary Tibetan writers although there does not seem to be a continuity between his writing and that of the later ‘new literature’ movement of post-Mao times. It is likely that his influence on art of the same period is even more tenuous, but his name is often extolled by contemporary artists. 10. Harris (1999: 50-55) discusses the reception of photo-realist painting styles in exile and the use of photography as iconic portraiture (2003), Tsewang Tashi (lecture and discussion November 2005). 11. Harris and Shakya (2004) show the way in which Lhasa was transforming during the 1930-40s, in particular through interaction with the British consul and photography. 12. Tsewang Tashi presented ‘20th Century Tibetan Painting’ at the 2003 International Association for Tibetan Studies Conference in Oxford. Thanks to Paola Vanzo for providing a draft copy. 13. Jamyang Norbu (1993), in one of his more subtle essays, comments on the cultural impact of communist art in Tibet, and Per Kvaerne (1994) echoes his sentiment of cultural degredation. Harris (1999: 151-162) provides an in-depth discussion of realism, socialist-realism, and thangka styles. 14. Wang Jing’s (1996) study is a brilliant critique of the myriad literary and artistic outbursts during the 1980s and early 1990s. 15. Li (2004) 16. Penba Wangdu (lectures, Tibet University September-October 2005) follows a series of articles by the master thangka painter, Tenba Rabten, that rigorously define the history and style of Tibetan thangka painting. Tenba Rabten’s studio/school sets the current standard for quality thangkas in Lhasa, with several other master painters operating similar style thangka studio schools. 17. Bentor (1993) offers a look at the thangka sellers in Kathmandu, but a fuller investigation of thangka shops in diverse areas such as Xining, Lhasa, and Kathmandu would be interesting. Kathmandu displays a growing variety of semi-psychedelic and flower-power type tangkas (perhaps borrowing from Karma Phuntsog’s examples), Lhasa tends to be much more conservative (although an over-percentage of wrathful deities and mandalas seems to on offer), I have no knowledge of Xining or Repgong which are said to have some of the best tangka artists. 18. See Harris’ (1999: 181-191) discussion of Gongkar Gyatso and the tea house meetings. 19. The Gedun Choephel Gallery has achieved considerable publicity through support from the Trace Foundation, New York, inclusion on the authoritative website <www.asianart.com>, a recent article by Craig Simons in the New York Times (2004), and the joint exhibition ‘Visions from Tibet’ in London, 2005. 20. This and the following statements, unless otherwise referenced, are taken from extended interviews with the artists in September 2004. More general views are culled from personal conversations with different artists, gallery owners, and Lhasa residents during the past eight years. I am translating freely from Tibetan to English; ‘gya-rig’ in Tibetan translates literally as ‘Chinese’ but refers in particular to Han people and should not be confused with ‘trong-guo’, the Tibetan phonetic rendering of ‘zhong-guo’, China. 21. Natalie Gyatso (2004) spoke at Gongkar Gyatso’s London gallery, The Sweet Tea House <www.sweetteahouse.co.uk> 22. Tsering Shakya (2001, 2004) makes it clear that to an emerging group of Tibetan writers in the late-1970s the questions of ethnicity and language were inextricable. Harris discusses the ‘staged authenticity’ problem of Tibetan ethnicity and artists, especially in exile (1999: 191-201). 23. Li (2004), introduction by Yu Jia written in Chinese, translator unknown. 24. Dru Gladney (2004) is has been most insightful among several scholars to deal with this tendency in arts and literature especially. Various articles in Steven Harrell (1995) and his own monograph (2001) confirm the kind of ambivalent exotification at a more micro-level with ethnographic studies of different groups in Yunnan. 25. The characterization of Tsering Dorje here is based on Natalie Gyatso’s (2004) presentation. 26. His sentiments echo those expressed by the now-successful Avinash Chandra, who, after a thoroughly modern upbringing and arts education was asked if he could paint ‘lions and tigers’ since he was Indian (Araeen 1990: 27). 27. Statements from: Tibet University lectures (November 2005), Jill Sudbury’s extensive videos filmed in July 2003 and made personally available; Natalie Gyatso (London, November 2004); and personal communication thanks to Eveline Yang in Lhasa (March 2005). 28. Gao Minglu (1999) discusses the importance of what he calls ‘political pop’ (others have called it ‘cynical realism’) and later ‘apartment art’ in the 1990s mainland Chinese art scene. An emphasis on performance, video, and interactive work continues in China today, as pointed out by Hou Hanru (2005) and other articles in the current issue of Flash Art (March – April 2005) and Contemporary (issue 72, 2005). 29. Geremie Barmé speaks of a cultural marketing craze in China generally, and the art scene in particular during the 1990s. 30. Interviews with an art teacher, interested collector, and art dealer from Beijing currently working in Lhasa (September 2004). 31. There was an environmental

art performance, ‘Living Water’, which took place in Lhasa

during 1996 but while the Beijing artist Song Dong’s piece ‘Printing

on Water’ has been exhibited internationally over a span of several

years (Asia Society, New York), the Tibetan artists that took part have

not been publicized (Tsering Nyandak and Tsewang Tashi, personal communication).

Gongkar Gyatso, now in London (www.sweetteahouse.co.uk),

has successfully incorporated conceptual and installation pieces into

his impressive body of work and has recently been increasing connections

with artists still in Lhasa. |