Metal sculptures of the Tibetan Imperial period

by Yury Khokhlov

article © Yury Khokhlov and Asianart.com

Published: January 24, 2013

Edited: December 01, 2018

Edited: February 04, 2019

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Production of metal sculptures during the Tibetan Imperial Period (600-842 AD) has been extensively documented by Tibetan historical sources[1Ulrich, Von Schroeder. Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet (Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications Ltd, 2001): 736- 739.]. However, only a few Tibetan statues have been attributed to that time and stylistic features of Buddhist art at this stage remain debatable.

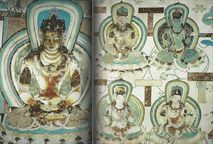

Fig. 1On the basis of two published sculptures attributed to the Tibetan Imperial period and two examples from my own collection, my research provides additional data and highlights key features of sculptural art during the Tibetan Imperial period. The study was inspired by a paper by Marylin Rhie Interrelationships between the Buddhist Art of China and the Art of India and Central Asia from 618-755 AD (1988) where she reveals connections between Buddhist art of Northern India, Afghanistan, Hindu-Kush, Swat, Kashmir, Central Asian Kingdoms and China at the time of the Tang dynasty [2Marylin M., Rhie. Interrelationships between the Buddhist Art of China and the Art of India and Central Asia from 618‐755 AD. (Supplemento n.54 agli ANNALI, vol.48, fasc.1). Napples: Instituto Universario Orientale,1988.]. Although these connections exist through the whole Tang period, she concentrated her research on the early and flourishing Tang when they are particularly intense. Probably due to an absence of published Tibetan material at the time of the research, Tibet was not included in her work. However, the Tibetan Empire was one of the key figures in the region and early Buddhist art in Tibet should have been in consonant with the discussed interrelations as well. In the light of the scarcity of securely datable artifacts from the Imperial period, comparative stylistic analysis of Tibetan objects in connection with datable contemporaneous examples from neighboring countries can be helpful for reconstructing major stylistic trends at the early stage of Buddhist art in Tibet.

Fig. 2A standing Bodhisattva (fig. 1) published by Rhie and Thurman in Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet was the first sculpture attributed to the Yarlung dynasty[3Marylin M., Rhie et al. Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet (New York; London: Harry N. Abrams, 1996):416.], though such an early date was called to question by some scholars in later publications [4Sotheby's catalog, 25 of March 1999, lot. 63 (a rare Tibetan copper figure of Bodhisattva 11/12 century).]. A figure of Bodhisattva from my own collection (fig.2) demonstrates a similar stylistic mode. In the following paragraphs, I am arguing that both pieces can be firmly attributed to the time of the Tibetan Empire.

The Bodhisattvas in fig. 1 and fig. 2 are portrayed in a stately manner with the right hip slightly outward and the left leg slightly bent which creates the impression that they are ready to step forward. Although the sculptures recall Nepalese examples, they display a mix of characteristics, which belong to various artistic traditions. They are hollow cast and have a rectangular opening in the upper part of the back sealed with a metal plaque (fig. 3).

Fig. 3 |

Fig. 4 |

The Bodhisattvas wear similar crowns (the upper part of the crown in fig. 1 is damaged) with a tall central section and two smaller side elements. The same motif can be found in the crown elements of niches of Licchavi caityas, where it represents lotus leaves and a lotus flower enclosed in scroll-work [5Niels, Gutschow. The Nepalese Caitya: 1500 Years of Buddhist Votive Architecture in the Kathmandu Valley. (Berlin: Axel Menges, 1997.) :124-126.] (fig. 4). A five-gemmed decoration in the center of the crowns depicts a lotus flower resting upon lotus leaves, which could symbolize Buddha Amitabha and thus both figures can be identified as Avalokitesvara[6See Gutschow : 33-34 for the recognition symbols of the Tathagatas in Licchavi art.]. Furthermore, the crowns are topped with a crest-jewel.

The Bodhisattva in fig.2 bears a close resemblance to early 8th century Padmapani and Vajrapani from Dhvaka Baha, Katmandu, Nepal (fig. 5)[7See the discussion on the date of the Dhvaka Baha caitya in Mary S., Slusser et al. The Antiquity of Nepalese Wood Sculpture: A Reassessment (Seattle and Washington, D.C.: University of Washington Press in association with the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2010.): 118.]. They share a slightly bent stance, massive shoulders, and relatively compact chest and thighs. With regards to facial features, the figure is very close to a wooden Bodhisattva (wood is radiocarbon tested to 550-680 AD) from Pritzker Collection (fig. 6) and the 8th century sculpture of Devi from the Cleveland Museum of Arts[8Ulrich, Von Schroeder. Indo-‐Tibetan Bronzes (Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications Ltd, 1981): 75G.].

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 7 |

Fig. 8 |

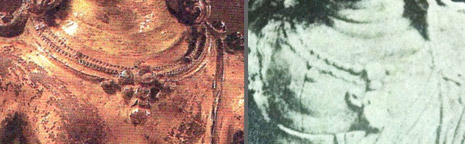

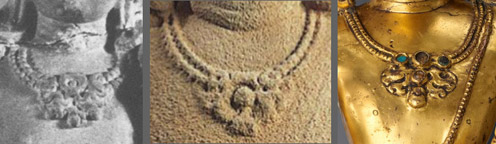

Fig. 9a

Fig. 9bBy contrast, the sculpture in fig. 1 is stiffer with shorter arms, a bigger head, lesser volume of the shoulders and a relatively bigger chest and thighs, which is closer to the 9th century Nepalese examples and particularly to Avalokitesvara from Gahiti, Patan, Nepal (fig. 7). At the same time, it possesses unusual qualities for a Nepalese sculpture with its powerful neck, which draws similarities to the mural in Yulin cave № 25 belonging to the period of the Tibetan occupation of the Hexi corridor in the late 8th and early 9th centuries and dated by scholars from the Dunhuang Academy to 821AD [9Jinshi, Fan. The Caves of Dunhuang. (Honk Kong: London Editions (HK) Ltd, 2010): 185.] (fig. 8). The figures in the mural reflect Tang dynasty aesthetics and resemble 8th century Chinese marble sculptures from Anguosi temple (figs. 9 A, B). The Bodhisattva (fig. 1) and Vairochana (fig. 8) share mighty torsos and long strong necks (note the lines on the necks go down to the level of the necklace). The facial features (lips, eyes and eyebrows) are very close as well. The arm bracelets resemble those worn by the Dunhuang Bodhisattvas (fig. 10), while the necklace is close to that in the Anguosi sculpture (fig. 11).

Fig. 10 |

Fig. 11 |

In comparison with the Dunhuang Vairochana (fig. 8), the Bodhisattva in fig. 2 is adorned with equally large arm bracelets and a necklace of a different type. An almost identical necklace with a single and large pendant can be found in post Gupta Indian sculptures: in the 7th century Sarnath figure of Manjushri from the National Museum, New Deli and the 8th/9th century Central Indian figure of Vishnu from the Norton Simon Foundation (figs. 12, 13).

Fig. 12 |

Fig. 13 |

In 1988 M. Rhie introduced the term "international Fondukistan style" which she applied to the group of materials dated to the 8th century from Tianlongshan (Shanxi province, China), Gilgit, Dandan-Uliq (Khotan) and Adzhina Tepe (Tadjikistan).[10Rhie, 1988: 33.] All of them reveal exaggerated gracefulness, soft movement and mannerisms that are manifested in the figures from Fondukistan. The Bodhisattva (fig. 2) could be considered as an example of this artistic trend as well (fig. 14). The figures share a wonderful sway of the torso, compact rib cage, contrasting juxtaposition of wide shoulders and a narrow waist and in Rhie's words 'plump and stiff arms lightly held away from the body'. Both are adorned with similar jewelry, namely a necklace with a single and large pendant and considerable arm bracelets with a somewhat similar decorative motif. Another comparable post-Gandharan example is the 7th century (?) Swat Bodhisattva from the Pakistan National museum, which is adorned with a comparable crown and a necklace with a single and large pendant (fig. 15).

Fig. 14 |

Fig. 15 |

Regarding Tibetan monuments, striking parallels can be found in the Tibetan stone carving in Drak Lhamo from Eastern Tibet attributed to the reign of Trisong Detsen (755-797) or slightly later (figs. 16, 17). The central figure has an equally impressive torso and a charming facial expression conveyed by curled corners of the lips. It was noted by Dr. A. Heller that outlines of the crown resemble those of the crown of the Bodhisattva in fig. 2 [11Amy Heller, personal communication, January 2011.] (fig. 18). The figures in the carving wear earrings with a flower motif similar to that in the Bodhisattva earrings. The Bodhisattvas in the carving show remarkable similarities with the Bodhisattva in fig.2. Their faces with distinctive jaw lines and small chins are particularly close. (fig. 19).

Fig. 16 |

Fig. 17 |

Fig. 18 |

Fig. 19 |

Fig. 20In addition, both sculptures have silver inlayed elements (eyes in fig. 1 and a band in the crown in fig. 2), that is a typical Indian practice and almost never seen in Nepalese art. The silver band on the base of the crown (close-up in fig. 4) is decorated in the same way as the Sogdian silver cup of the 8th century from the State Hermitage Museum (pl.20). Dr. A Heller noted similarities between Sogdian and Tibetan silverwork in her work in 1999.[12Amy, Heller. Tibetan art: tracing the development of spiritual ideals and art in Tibet, 600-2000 A.D. (Milan: Jaca Books, 1999): 9.]

Whilst the two sculptures under scrutiny resemble Nepalese examples, their Tibetan origin can be confirmed by similarities with the Eastern Tibetan rock carvings. Furthermore, they demonstrate a mix of non-Nepalese stylistic features that directly connect them with Central Asian and post-Gupta Indian examples. The Bodhisattva in fig. 2 can be dated to the 8th century while the figure in fig. 1 possesses stronger connections with relatively later material and thus most likely belongs the first part of the 9th century.

In the following section, I would like to discuss a particular style represented by another sculpture attributed to the Late Imperial period, which was published in Himalayas: An Aesthetic Adventure in 2003 (fig. 21)[13Pratapaditya, Pal. Himalayas: An Aesthetic Adventure (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003): 169.]. It shows the figure of Buddha Vairocana from a private collection dated by Dr. Pal to the ninth or 10th centuries. The format of the publication, however, did not allow the authors to carry out a deeper investigation into its distinctive features. A statue of Bodhisattva Maitreya from my own collection (fig.22) shows a similar style. I thus intend to define and discuss their characteristics and possible origins in the following paragraphs.

Fig. 21 |

Fig. 22 |

Fig. 23 |

Fig. 24 |

Fig. 25 |

Vairochana (fig. 21) and Maitreya (fig. 22) share elongated torsos and limbs without any muscular definition, wide shoulders, relatively thin necks and recall 7th century stucco figures from the Great stupa in Nalanda, India (fig. 23). The figures are adorned with a short necklace similar to that in Nalanda Manjusri (fig. 23); pleats on the shoulders are arranged in the same way as in the Nalanda figure as well. Foliage in the necklaces, arm bracelets and petals of the crowns recall those in Nepalese sculptures (see example in fig. 7). The tall five-pointed crowns are fastened with a ribbon with swirling ends and two flowers that are attached to the base. The crowns consist of a hooplike base topped with three bars in the form of moon crescents. In Maitreya's crown, the ends of the moon crescents are held by kirtimukhas spitting gems. Three tall triangular petals grow from the moon crescent bars, while two leaf-like petals fill the space between them; in Maitreya's crown they grow from kirtimukhas. Images of kitimukha with foliage are known at least from the Gupta period in India; for instance, this motif was widely used in decorations of the Ajanta caves (fig. 24). However, the type of the crowns is not Indian; similar examples can be found in pre-Tang Chinese sculptures from Northwest China (fig. 25).

Similarities with the Chinese sculptures are not surprising as one can assume that the Tibetans would have met such imagery in the 7th century during their initial contacts with Chinese Buddhism.

Connections with Nalanda imagery are expected as well. Interactions between Tibetans and Buddhist communities in the Bihar region of India during the Imperial period are well documented; Nalanda Mahavihara and surrounding monasteries became the leading Buddhist institutions in Northern India from the beginning of the 7th century and their popularity in Tibet is reflected in the first Tibetan monastery, Samye, which was built in 762-766AD on the model of the great monastic complex of Odantapuri. The main building consisted of three stories fashioned in Tibetan, Chinese and Indian styles by craftsmen of respective origins[14Von Schroeder, 2001: 723.]. One can envisage the probability that early sculptures in Tibet also displayed an admixture of those three styles.

Early Tibetan testimonials at Denma Drak and Beedo temple show comparable tall crowns and elongated bodies (fig. 27). Another comparison can be made with Bodhisattvas from a group of Dunhuang banners (fig. 28), which display similar elongated proportions; thin necks; and wide and rounded shoulders. Maitreya in fig. 22 and the Dunhuang Bodhisattvas wear similar low-hanging and flower-like earrings.

Fig. 27 |

Fig. 28 |

Fig. 29 |

An 11th century clay figure from rKyang bu monastery can be considered as a later development of the same style (fig. 29). Amoghasiddhi has a somewhat similar crown with three crescent moon elements and tall leaf-like petals connected by two kirtimukhas spitting jewels. The face has certain connections to that of Maitreya (fig. 22), but the torso is more muscular, arms are considerably shorter and the head is larger. The clay figure is similarly clad in a dhoti and a sash made of the same fabric and wears similar earrings.

Fig. 30Moreover, our images (fig. 21, 22) somehow recall gilt bronzes excavated in Nalanda and datable to the seventh and eighth centuries [15Von Schroeder, 1981: fig. 49F, 50E-50G, 51A, 51B, 52E.] (fig. 30). The sculpture of Maitreya has so called "stays" or struts, technical casting devices, which were not removed, but instead left to support the arms and are gilded; this technical device is one of the distinctive features of the early Nalanda bronzes as well [16Mathur, Asha Rani. The Great Traditions: Indian Bronze Masterpieces. (New Delhi: Festival of India, 1988): 119.]. Stylistic varieties found in Indian sculptures must have reflected in Tibet, as according to some textual sources, sculptures in Tibet during the reign of Ralpacan (815-838) were mostly made by Indian artists and were similar to sculptures of the Magadha region. [17Von Schroeder, 2001: 1086.] In view of what has been discussed, the two figures under examination were likely cast in Tibet, sometime in the 9th or early 10th century.

Fig. 31Another sculpture of this type can be found in the picture of Lima Lhakhang in Potala Palace taken by M. Henss in 1993 (fig. 31, second sculpture from the left)[18]. Striking similarities with the figure of Maitreya (fig.22) are obvious and the sculptures most probably belonged to the same set. There is an interesting detail: the presented sculptures and the Potala figure possess an unusual characteristic by wearing their wrist bracelets very high on the forearms. The author was not able to find any strong comparisons for this feature and its source requires further investigation.

To summarize, the first pair of sculptures represents the Nepalese artistic tradition, which has been established in Tibet since at least the 7th century. The Bodhisattva in fig. 1 reveals the influence of the high Tang style, which most likely became prominent in Tibetan art during the occupation of the Hexi corridor. The Bodhisattva in fig. 2 is directly connected with post- Gupta Indian examples and draws an interesting parallel with post-Gandharan art of Fondukistan and Swat.

The second pair shows an innovative Tibetan mode based on artistic styles from the Bihar region of India and Northwest China.

What is more, all four statues are recognizably Tibetan and they can be easily distinguished from their foreign counterparts.