Articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

Download the PDF version of this article

This article is reprinted from the catalogue, Art of the Himalayas: The Collection of Roshan Sabavala, Pundole's Auctions, Mumbai, December 16 2014, with kind permission of Pundole's. Please note that as per Indian law, all lots in this auction are Non Exportable and are registered with the Archaeological Survey of India. By clicking on the articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal link above, the reader will be able to view an index of all the articles published to date on Asianart.com by Dr. Pal.

December 09, 2014

text and photos © asianart.com and the author except as where otherwise noted

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

1.

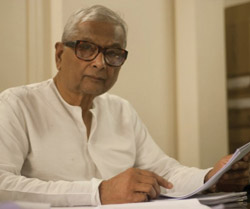

Roshan Sabavala, 1918–92 The name Sabavala has been a familiar one in the cultural domain of India, and particularly Bombay/Mumbai, over the second half of the 20th century. It belonged to two brothers, both now deceased: Sharokh (1918–2012) and Jehangir (1922–2011). The latter was an internationally famous artist; the former was a journalist, a veteran of World War II, a distinguished director of the Tata Group (and a close associate of J.R.D. Tata), a philanthropist and a civic leader to whose initiative Mumbai’s citizens owe much for the beautification of stretches of the city. Sharokh’s ornament was Roshan (1918–92) who was also a well-known figure in the cultural realm of Bombay (she did not witness the city’s rechristening) and a collector of art (figure 1).

Fig. 1: Wedding portrait of Roshan and

Shahrokh Sabavala, 1947Roshan’s father Jehangir (a popular name among the Parsi community) Batliwalla was a physician who decided in his early 40s to give up his practice and with his wife Maneck roam the world. The two young girls, Roshan and her sister Kaity, were deposited at a school in Monte Carlo, France, under the care of a local Parsi family. They grew up as accomplished young ladies and learned to speak French as fluently as English. Roshan and the Oxford-educated Sharokh were married in February 1947 and lived the first few years of their life together at the Taj Mahal Hotel. On Independence Day 1947 they were witness to the hotel being thrown open to the public who were out celebrating on the streets.

I don’t quite remember when I first met Roshan and Sharokh Sabavala but it must have been soon after she became General Advisor to Marg in 1976: it was Marg that brought us together. I recall with much pleasure the dinner parties she hosted whenever I visited Bombay, not in the charming villa on Worli Sea Face, which bears the name “Beau Rivage”, but in a private dining room at the Taj Mahal Hotel where she was certainly la dame formidable, as was evident from the exceptional attentiveness of the staff who were continuously on their toes until the parties ended. In the beginning I used to think she must own the place!

Roshan and Sharokh were so unlike one another, but they made a complementary couple: he with his quiet elegance, keen intellect and interest in politics and social issues, vast experience in the worlds of business and the media and his endless store of stories about all the interesting people he had met; she with her French schooling, aristocratic bearing, slightly imperious but natural grace, her deep interest in culture, compassion for the unfortunate and, of course, her passion for art, which is what attracted her to Marg from its foundation in 1946. She nurtured the institution during a difficult period in its existence, from a few years before the departure of its founding editor Mulk Raj Anand (1905–2004) until her untimely death in 1992. Sharokh went on to be a nonagenarian and I enjoyed his congenial companionship for years. He was unquestionably one of the most wonderful men I have had the pleasure and privilege of knowing.

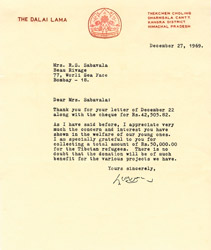

Fig. 2: A letter from His Holiness

Tenzin Gyatso, XIV Dalai LamaA European education generally instils in a student an interest in art and music and Roshan was no exception. Moreover, she was a Parsi and I am yet to meet an affluent Parsi who is not keen on the visual arts or classical Western music, or both. In any event, by the 1960s Roshan had not only become associated with the founders of Marg but also had come under the influence of Mrs. Madhuri Desai (1910–74) who was a lover of Indian art. Initially interested in Indian and Nepali art, Roshan was soon drawn to the Tibetan refugees in the city with their bundles of artefacts and jewelleries. In December 1967, together with her sister Kaity (Nariman) she organized an exhibition of Tibetan material culture at the Jehangir Art Gallery, which was graced by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Thereafter the two sisters opened a small shop in Mumbai to sell Tibetan artefacts to help the refugees, which elicited commendations from and correspondence with His Holiness (figure 2).

In 1970 the couple and their twin daughters moved to Delhi soon after Sharokh joined the Tata Group. They lived there four or five years, and it was in the capital that Roshan found new opportunity to develop her interest in Himalayan art. In a personal communication one of the twins – Radhika – recalls how a long line of Tibetan refugees used to ‘assemble daily’ outside their Prithviraj Road residence gate ‘with their wares tied in small cloth bundles’, waiting to meet Roshan.

I too remember, in my days as an undergraduate at St Stephen’s College, Delhi between 1952 and 1956, how the Tibetan refugees would lay out a remarkable array of artefacts that included bronzes and ritual objects by the hundreds on cloths spread on the wide footpath in front of the Imperial Hotel in Janpath, the long iron railing behind them being festooned with thankas and carpets. I had little interest in art of any kind then, but on a later visit in 1961 for the centenary celebrations of the Archeological Survey of India, with my eyes opened as a post-graduate student, I too rummaged around and picked up a small South Indian figure of dancing Krishna and a bronze Buddha from Nepal as gifts for my mother. Promptly my first acquisitions were placed in her domestic shrine and worshipped for the rest of her life.

Fig. 3: IndraConsidering the lively scene for collecting Indian art among the wealthy members of Bombay’s Parsi community, that Roshan too would be tempted to dip into this rich resource is not surprising. After her wedding she would have become familiar with the formidable collection of Indian and Persian art of Sir Cowasji Jehangir (1879–1962) who was Sharokh’s maternal uncle. Even occasional social visits to Readymoney House (alas no longer extant) would have been an aesthetic adventure for the young lady.[1] Moreover, she was also familiar with the vast collection of the Tata brothers – Sir Dorab (1859–1932) and Sir Ratan (1871–1918) – that had become the treasures of the local museum then known as the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India and now renamed Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS). While Sir Cowasji was not immersed in Himalayan art, the Tata Collection includes a substantial amount of art from both Nepal and Tibet.[2] A unique piece in the collection is a tiny gilded Indra, a form invented by the Newar artists of Nepal, but unusually nestled in a hunk of turquoise, a semi-precious stone much admired by Tibetans (figure 3). Roshan must have visited the museum and seen such objects displayed in its Himalayan gallery.

No less important was the Sabavalas’ close circle of friends in Bombay, that included the celebrated scientist Homi Bhabha who collected contemporary art, Pupul Jayakar who preferred Indian antiquities, Madhuri Desai, whose collection of sculptures is now in the Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum in Ahmedabad, and Douglas Barrett of the British Museum who was a frequent visitor to Bombay.[3] At Marg, Roshan met, besides Mulk Raj Anand, Anil and Minnette de Silva and, of course, Karl Khandalavala (1904–95), a pre-eminent art historian and one of the last great Parsi collectors of the Raj with an eclectic taste. A prominent lawyer at the Bombay High Court with a flourishing practice, Khandalavala still made time for his passionate study of Indian art. He was a polymath in his art-historical interest; he appreciated all areas of the subcontinent’s art including the Himalayan cultures.

Fig. 4: A Mother Goddess (Matrika)Khandalavala not only acquired a number of fine bronzes from Nepal but wrote several important articles in the early issues of Marg, a magazine he, along with Roshan, supported throughout his life.[4] One of his splendid acquisitions, a 14th-century Mother Goddess, is illustrated here (figure 4).[5] More interesting is that he kept records of some of his sources. Thus we learn that one of the Himalayan bronzes in his collection was a gift to his wife from Sir Cowasji who had bought it from the dealer Gazdar who in turn had acquired it from Nasli Heeramaneck.[6] Heeramaneck was also the source of another splendid gilt bronze Nepali Vasudhara of c. 1400, which Khandalavala bought for Rs. 1,600, while a Bodhisattva of c. 1500 was acquired from a Mrs. Khan for Rs. 750.[7] Yet another bronze depicting Akshobhya Buddha dated 1641 was bought for Rs. 300 from a dealer named Popley who worked from Amritsar.[8] Both Mrs. Khan and Mr. Popley had acquired the pieces from British military officers, likely during World War II. Those were the days!

Apart from such close associations that whetted her appetite for Himalayan art, it should be emphasised that Roshan was also moved by the plight of the Tibetan refugees who poured into the country in the 1960s. They had fled Tibet with their few precious possessions following the Chinese invasion in 1949 and the subsequent flight of the Dalai Lama to India. Partly therefore she began buying from these hapless refugees out of compassion, and so her interest in Tibetan art was motivated as much by humanitarian reasons as by aesthetic impulse.

Acquiring Tibetan and Nepali art was not limited to collectors in Bombay. As early as the turn of the 20th century, Calcutta (now Kolkata) was also an active centre of collecting arts from those countries. Being then the capital of India, not only did it attract Tibetans, but it was from Calcutta that diplomatic, political and even military (as for instance, the Younghusband expedition of 1904) missions to Tibet originated. Sikkim, Kalimpong, and Darjeeling in the Himalayan foothills had large Tibetan communities and monasteries and the Nathula Pass in north Sikkim offered a popular route for both traders and pilgrims between Tibet and India. Apart from the itinerant lamas who regularly visited Calcutta to sell Tibetan wares, mentioned by the artist Abanindranath Tagore (1871–1951) in his autobiography, we learn from other sources, particularly the art historian and collector O.C. Gangoly (1881–1974) about dealers in Calcutta with works from both Nepal and Tibet.[9]

Fig. 5: Indra/Lokeshavara with GuardiansAmong the earliest collectors of Himalayan art in Calcutta were Sir John Woodroffe (1865–1936) and Percy Brown (1872–1955). A judge of the Calcutta High Court and a pioneering Western practitioner and scholar of Tantra, Woodroffe was an enthusiastic and devout collector as well as an enthusiastic member of the Acquisition Committee of the Gallery of Calcutta’s Art School, which is now integrated with the Indian Museum. Unfortunately Woodroffe’s collection was looted during World War I in Europe where it was taken after his retirement, but the collection in the museum includes a number of Himalayan objects acquired during his committee membership (figure 5).

Brown came to Calcutta from Lahore in 1909 as the Principal of the Art School. He had begun collecting in Lahore and continued to do so in Calcutta. Not only was he one of the first artists/art historians to collect Himalayan art but he wrote about it extensively – including one of the earliest books on the arts of Nepal titled Picturesque Nepal, published in 1912. Unfortunately, the ultimate fate of his collection is not known, but in the 1950s Robert Skelton became familiar with the objects, especially the thankas, which were stored at the Victoria and Albert Museum soon after Robert joined the institution in 1950.[10] Unlike Woodroffe who collected Himalayan Tantric art with the zeal of a practitioner, Brown’s interest was purely historical.

Fig. 6: A floor lamp from NepalAmong the earliest Indian collectors of Himalayan art other than Abanindranath were the Ghose brothers – Anu and Ajit. Their exact dates are uncertain, but they began collecting in the 1890s. Ajit Ghose is well known as a pre-eminent connoisseur of Indian painting, who first recognised the distinctive early Basohli school, but he also appreciated Himalayan art and possessed illustrated manuscripts from Nepal and thankas.[11] It is not possible today to easily trace the fate of the extensive collection, but Ajit’s interest in Tibetan art can be gauged from his articles in such journals as Rupam, published in the 1920s and edited by O.C. Gangoly.

Gangoly too was not only an avid collector of Himalayan art both from Nepal and Tibet but also wrote about them in Rupam. He had a diverse collection of lamps from all over the subcontinent but always considered those from Nepal to be the best. Indeed, before Roshan Sabavala, O.C. Gangoly was probably the first connoisseur to admire the charm of Tibetan ritual objects. I illustrate here an impressive Nepali floor lamp now in the possession of one of his grandsons (figure 6).

Fig. 7: Amitayus BuddhaLike Calcutta, both Patna and Banaras were good sources for acquiring Himalayan art. In Patna Diwan Bahadur Radha Krishna Jalan (1882–1954), an eclectic and insatiable collector, as well as Gopi Krishna Kanoria (1917–1987), known primarily as a great connoisseur of Rajput paintings, acquired objects from Kashmir and Tibet. One of the largest and earliest Tibetan thankas outside of Tibet was obtained in the early 1960s from the Jalan Collection by Nasli Heeramaneck and is now in the eponymous collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (figure 7). Patna also houses another private collection of Tibetan art formed in Tibet by the explorer/scholar Rahul Sankrityayan (1893–1963).[12]

Fig. 8: Vairochana BuddhaAnother early admirer of Himalayan art was Rai Krishnadas (1892–1980) of Banaras, which is why the Bharat Kala Bhavan today has a fine but little-known collection of objects from both Nepal and Tibet. I had the pleasure of studying these while I was employed for a year in Banaras in 1966–67 and subsequently contributed an essay on the bronzes of Nepal for the commemoration volume in honour of Rai Saheb.[13] Here I illustrate one early and outstanding thanka from the collection (figure 8). It is a 13th century painting in a now familiar style – as encountered in the ex-Jalan thanka – which was first brought to our notice by the great Tibetologist Giuseppe Tucci in 1949.[14] I do not know whether Patna’s Diwan Bahadur or the Rai Saheb of Banaras was familiar with Tucci’s book when they bought their thankas or intuitively recognised their importance when offered the works. As far as I know the Bharat Kala Bhavan example is the only one of its kind on the subcontinent.

An important collection of Himalayan art has been formed in the second half of the 20th century by Suresh K. Neotia of Calcutta, which can be seen and studied at the Jnana-Pravaha museum in Banaras. It includes objects of historical significance from both Nepal and Tibet, some of which are well known to Himalayan art scholars. Fortunately the collection has been catalogued and published, unlike most other museum collections in the country.[15]

Roshan Sabavala not only inherited the impulse to collect Himalayan art from worthy predecessors, she was the last of the Parsi collectors though not the least in her obsession. Primarily her interest was in works from Tibet and she voraciously acquired metal statues, thankas and ritual objects. Serendipity also brought her one charming stone sculpture from Kashmir, a couple of attractive metal images from Northeast India (that had probably travelled to Tibet in the 12th century, to return home centuries later) and a few objects from Nepal. With 300+ objects in the collection, she had certainly outdone the Tata brothers numerically.

Of course, it should be emphasized straightaway that the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley were a constant presence in Tibet as traders, bankers, patrons of Tibetan monasteries and above all as artists. In fact, the Newari aesthetic impulse is so overwhelming in Tibetan art that, having now devoted half a century to the study of Himalayan arts, I still hesitate to distinguish between what was made in Nepal and what was created in Tibet by a Newar artist for a Tibetan patron. With this caveat I will now discuss a small selection of objects from the collection as a tribute to my friendship with Roshan.

Lot 1The earliest piece in the collection is neither from Nepal or Tibet but from Kashmir (lot 1). It is a small but elegant tableau representing the Hindu Holy Family of Shiva and his spouse Parvati and their sons Kumara and Ganesha, with Shiva’s bull mount. Created for a Hindu patron for domestic worship around 1000 CE, to my knowledge this composition represents perhaps the earliest formal family portrait, divine or mortal, in art in any ancient culture. It is also a rare tableau, for in most surviving examples from Kashmir the couple is shown standing rather than seated so intimately on the bull, which turns his head towards the divine riders in admiration while the two sons stand sentinel-like at either edge of the pedestal.

Lot 8 Among the sculptures from the Pala period of about the 12th century is a fine tantric couple in a vigorous sexual embrace (lot 8). The cosmic Vajrayana deity Hevajra with his female spouse shares some iconographic traits with the Hindu Shiva in his Bhairava or angry form, in the arrangement of the ascetic hairdo (jatamukuta), his third eye, the skull ornaments etc.; but the composition of the passionate couple is typically an invention of Buddhist mystics. In fact the pair trample Bhairava and Kalaratri who symbolize obstacles, in an obvious display of sectarianism. Overall the coupling figures express a dynamic energy that is unlike anything encountered in Hindu iconography.

Lot 40By contrast, a gilded bronze Buddha among a number of Buddha figures in the collection is a study in tranquility by a Newari artist (lot 40). Seated on a lotus in the classic posture of meditation, the Buddha stretches out his right arm with the hand forming the typically Buddhist gesture known as bhumisparshamudra – as when he called upon the earth to witness his repulsion of Mara’s temptation at Bodhgaya at the end of his meditation under the bodhi tree to signify his enlightenment. He is clad in the robes of a monk but his head is adorned with a tiara indicating that this image is of a transcendental Buddha (Sambhogakaya or Body of Bliss or Enjoyment) rather than that of the historical teacher. This is a typical example of a sculpture whose exact origin is difficult to determine. As I noted earlier, it could have been cast in a workshop in Nepal or in Tibet by the Newar artist.

Lot 72 In another similar Buddha image cast about the same time, and also crowned, two iconographic differences are noteworthy (lot 72). Here a thunderbolt is placed on the top of the lotus base, which makes it possible to more precisely identify the figure as the transcendental Buddha Akshobhya; and a turquoise is added to the forehead as the urna or the tuft of hair, one of the 32 marks of a superhero (mahapurusha). The use of such inlay of semiprecious stone is an indicator of its manufacture for a Tibetan patron. Notable further is the difference between the shapes and modelling of the bodies of the two Buddha figures, clearly reflecting divergence in their proportions and in the individual preferences of artists. All Buddhas are therefore not alike, and such variations are evident among the several other Buddha figures in the collection as well, attesting to the keen and discerning eye of the collector.

Lot 42A unique bronze of imposing size, undoubtedly from Tibet of the 15th or 16th century, portrays the complex and cosmic form of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (lot 42). The embodiment of compassion, he is one of the most popular of the Mahayana/ Vajrayana Buddhist pantheon whose cosmic form was first conceived with eleven heads and eight arms, an iconography that was famous by the Tang period (618–907) in Central Asia and China and is first encountered in a cave shrine (c. 6th–7th century) in Kanheri near Mumbai. Later, the number of arms was increased to 1,000 to make the image even more potent. With his tall, slender and columnar figure, the Bodhisattva stands like a cosmic pillar that connects the earth and the sky, while his radiating arms form a circle or mandala embracing the cosmos. This image is clearly a tour de force of compositional harmony and technological finesse.

Lot 41 No less interesting is a painted version of the theme, though later by several centuries and from Nepal rather than Tibet (lot 41). Despite the style of his attire with a long red skirt flaring at the bottom, the swirling ends of the long scarf and the overlay of the green apron imitating Tibetan mode derived from Chinese fashion, it is clear from the portrayal of the donors at the bottom that the painting was commissioned by a Newar. Although not very large, it too is a rare depiction of the deity’s cosmic form reflecting the partiality of the Newar patron – probably a trader with Tibet – for Tibetan Buddhism. Indeed, many paintings of the 18th and 19th centuries bear inscriptions that clearly state that they were painted in Tibet, specifically in the Tashilhunpo monastery, for Newar patrons.[16]

Perhaps the most distinguished contribution – and the most popular among connoisseurs today – are the thankas, religious paintings made on cotton most often imported from India, and elaborately mounted on Chinese silks and brocades, especially those rendered from the 16th century onward; a type that especially appealed to Roshan Sabavala. Until the late 1990s, collectors of Tibetan art in the West generally preferred earlier thankas, which fetch high prices and hold little appeal for the Chinese. Interest among the nouveau riche Chinese since the turn of the millennium has grown exponentially with their wealth and so has the desire for acquiring Tibetan art, which once was shunned. As a result, thankas of the more recent centuries, particularly those showing influence of Chinese style with strong landscape elements, are now particularly sought after in art markets from Beijing to New York. Roshan Sabavala’s fondness for these thankas is self-evident in the catalogue.

It is not possible to discuss individually the many thankas she collected and I will confine myself to a few comments on a small group. Most of the thankas belong to the Gelukpa order – founded by the great reformer and charismatic teacher Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) – which instituted the unique religio-political system of the Dalai Lama. An attractive group of thankas depicts the vision of Tsongkhapa, who always wears the yellow hat and holds a sword and book – attributes of Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom (lot 71). They are among the finest examples of a style of landscape painting that is both indigenous and aesthetically attractive. With clarity of composition and audacious juxtaposition of natural and supernatural elements bathed in uniformly serene light, they are appropriate visual expressions of visionary landscapes of the mind.

Quite different is the style of landscape representation in two other thankas in the collection. The natural elements, the setting and the compositional mode with dense vegetation and psychedelic rock formations clearly derive from earlier Ming (1368–1644) Chinese religious painting (lots 61 and 67). The two examples are probably contemporaneous and were executed c. 1700. One represents the great Mahasiddha of India, Virupa whose teachings had a profound effect in Tibet (lot 67). The other likely originated locally and is the Sage of Long Life who may be identified by the six iconographic elements of longevity enumerated in the catalogue entry (lot 61).

The last thanka discussed here is a small mandala of Heruka (lot 82). Mandalas comprise yet another theme of the Tibetan painting tradition, unsurpassed in any other Buddhist culture both for its religious significance and visual diversity. Although the mandala as a ritual instrument of meditational praxis was introduced from India, for the sheer variety of their forms and brilliant technical virtuosity the Newar and Tibetan artists are outstanding in their creative impulse. The Heruka mandala in the collection, though relatively late and of modest proportions, is a proficient example of the genre.

Lot 19It remains for me to discuss one or two examples of the large numbers of Tibetan ritual objects in metal of which Roshan was particularly fond. Among the earliest is a group of chortens or stupas known generally as “Kadampa” chortens, as they were made mostly for the use of devotees of the Kadampa order, following the teachings of the great Indian spiritual master Atisha Dipankara (985–1054) who journeyed to Tibet in 1040 and died there. Distinctive in their appearance and remarkably consistent in their forms, these small chortens are now difficult to find and should be welcomed by all those seriously interested in Tibetan art (lot 19).

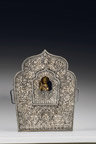

Lot 109Another distinctive religious object of Tibetan Buddhist culture is the portable shrine known in the language as a ga’u. Made frequently of silver, the ga’u in any form is rarely found in other Buddhist cultures. While similarly shaped portable shrines are first encountered in the art of Gandhara, no Indian specimen has survived. In the Tibetan religious realm, however, they were extremely popular and rarely would a trader or pilgrim travel without one. In one example in the Sabavala Collection not only do we encounter fine craftsmanship, but also the gilded figure of the primordial Buddha of Vajradhara within the shrine is intact, therefore making it a two-for-the-price-of-one object (lot 109).

Lot 105Apart from these travelling shrines – even more necessary for all of us who travel in these volatile and hazardous times – another ritual object typical of Tibetan culture is the butter lamp (lot 105). Everyone who has visited a temple or a private home in the Tibetan cultural zone (which was much larger than the country itself) must have been impressed with the numerous butter lamps that flicker constantly to create a mesmeric and mysterious ambience enhanced with the smell of the melting yak’s-milk butter. Gifting lamps to a shrine is one of the most precious expressions of piety among Buddhists as well as Hindus.

The lamp is also symbolic of the ancient rite of fire of Zoroastrianism, the religion older than the Buddha which now survives among the Parsis, the community to which Roshan Sabavala belonged. The Buddha had exhorted each of his followers to be a lamp unto the world, and appropriately the name Roshan (or roshni) literally means light or effulgence. Rarely was an infant so aptly named at birth. May the lamps collected so avidly by this “lady of light”, and now changing ownership, enlighten generations of new devotees of Tibetan art.[17]

Los Angeles, Divali 2014

Notes

1. A selection from the collection was exhibited in 1965. See Karl Khandalavala and Moti Chandra, Miniatures and Sculptures from the Collection of the late Sir Cowasjee Jehangir, Bart., Bombay, 1965. Sir Cowasji, however, did have some Nepali bronzes and presented a fine example to Mrs Meherbai Khandalavala, as mentioned below.

2. Pratapaditya Pal in association with Sabyasachi Mukherjee and Rashmi Poddar (ed.), East Meets West: A Selection of Asian and European Art from the Tata Collection in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2010.

3. Ratan Parimoo, Treasures from the Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum, Ahmedabad, 2012. Douglas was an authority in Chola art but also keenly interested in the arts of Nepal. He and Madhuri joined me on a trip to Nepal in the autumn of 1966.

4. Not only did Khandalavala publish articles in Marg on other fellow collectors of Bombay, such as R.S. Sethna and S.K. Bhedwar, he also wrote on other aspects of Himalayan art. See the bibliography in the Khandalavala catalogue cited in note 5.

5. Kalpana Desai and Pratapaditya Pal, A Centennial Bouquet: The Khandalavala Collection of Indian Art in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2004, cat. 19. A companion piece depicting the goddess Vaishnavi is in the CSMVS (see Kalpana Desai, Jewels on the Crescent: Masterpieces of the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2002, cat. 219). Possibly the two bronzes were offered together to the museum, which could afford only one, and so Khandalavala bought the other. The two are now reunited.

6. Kalpana Desai and Pratapaditya Pal, A Centennial Bouquet: The Khandalavala Collection of Indian Art in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2004, cat. 25.

7. Kalpana Desai and Pratapaditya Pal, A Centennial Bouquet: The Khandalavala Collection of Indian Art in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2004, cat. 20 and 21.

8. Kalpana Desai and Pratapaditya Pal, A Centennial Bouquet: The Khandalavala Collection of Indian Art in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2004, cat. 22. I have so far been unable to identify Mrs. Khan. A second bronze from Rana, who must have been a Nepali dealer, was purchased for Rs. 600 (ibid., cat. 23), while an impressive image of Tara with an elaborate base and torana was acquired from an unknown source sometime in 1937–40 for the princely sum of Rs. 105 (ibid., cat. 24).

9. This brief account of collecting Himalayan art in India between 1900 and 1950 is based on my current research for a book on collectors of pre-modern art in the twilight of the Raj, to be published in 2015 by the Marg Foundation.

10. I am grateful to Robert Skelton for this information.

11. Some of the Himalayan artworks bought by A.K. Coomaraswamy for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts were likely from the Ajit Ghose Collection.

12. I believe the Sankrityayan Collection now is in the K.P. Jaiswal Institute in Patna.

13. Pratapaditya Pal, “Some Nepali Bronzes in Bharat Kala Bhavan”, Chhavi, Vol. 1 edited by Anand Krishna, Banaras, 1971.

14. Guiseppe Tucci, Tibetan Painted Scrolls, 3 vols., Rome, 1949.

15. R.C. Sharma, Kamal Giri and Anjan Chakraverty, Indian Art Treasures: Suresh Neotia Collection, New Delhi, 2006.

16. See discussion in Pratapaditya Pal, The Arts of Nepal, II: Painting, Leiden, 1978, pp. 149, 153–54, and figs. 214–18, of which the dated painting of 1695 representing the cosmic form of Avalokiteshvara (lots 41 and 42) belongs to the Bharat Kala Bhavan.

17. I am grateful to Radhika Sabavala for providing the biographical information about her parents, to Anujit Gangoly for the image in Figure 6, to Jeff Walt of the Rubin Museum of Art, New York for the identification of the thanka in lot 67, Rivka Israel for style editing, to my assistant Nancy Rivera for her diligence in preparing the manuscript for this Introduction in record time, to Robin and Sonali Dean for the catalogue details, and to Edward Wilkinson for references.

1. A selection from the collection was exhibited in 1965. See Karl Khandalavala and Moti Chandra, Miniatures and Sculptures from the Collection of the late Sir Cowasjee Jehangir, Bart., Bombay, 1965. Sir Cowasji, however, did have some Nepali bronzes and presented a fine example to Mrs Meherbai Khandalavala, as mentioned below.

2. Pratapaditya Pal in association with Sabyasachi Mukherjee and Rashmi Poddar (ed.), East Meets West: A Selection of Asian and European Art from the Tata Collection in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2010.

3. Ratan Parimoo, Treasures from the Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum, Ahmedabad, 2012. Douglas was an authority in Chola art but also keenly interested in the arts of Nepal. He and Madhuri joined me on a trip to Nepal in the autumn of 1966.

4. Not only did Khandalavala publish articles in Marg on other fellow collectors of Bombay, such as R.S. Sethna and S.K. Bhedwar, he also wrote on other aspects of Himalayan art. See the bibliography in the Khandalavala catalogue cited in note 5.

5. Kalpana Desai and Pratapaditya Pal, A Centennial Bouquet: The Khandalavala Collection of Indian Art in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2004, cat. 19. A companion piece depicting the goddess Vaishnavi is in the CSMVS (see Kalpana Desai, Jewels on the Crescent: Masterpieces of the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2002, cat. 219). Possibly the two bronzes were offered together to the museum, which could afford only one, and so Khandalavala bought the other. The two are now reunited.

6. Kalpana Desai and Pratapaditya Pal, A Centennial Bouquet: The Khandalavala Collection of Indian Art in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2004, cat. 25.

7. Kalpana Desai and Pratapaditya Pal, A Centennial Bouquet: The Khandalavala Collection of Indian Art in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2004, cat. 20 and 21.

8. Kalpana Desai and Pratapaditya Pal, A Centennial Bouquet: The Khandalavala Collection of Indian Art in the CSMVS, Mumbai, 2004, cat. 22. I have so far been unable to identify Mrs. Khan. A second bronze from Rana, who must have been a Nepali dealer, was purchased for Rs. 600 (ibid., cat. 23), while an impressive image of Tara with an elaborate base and torana was acquired from an unknown source sometime in 1937–40 for the princely sum of Rs. 105 (ibid., cat. 24).

9. This brief account of collecting Himalayan art in India between 1900 and 1950 is based on my current research for a book on collectors of pre-modern art in the twilight of the Raj, to be published in 2015 by the Marg Foundation.

10. I am grateful to Robert Skelton for this information.

11. Some of the Himalayan artworks bought by A.K. Coomaraswamy for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts were likely from the Ajit Ghose Collection.

12. I believe the Sankrityayan Collection now is in the K.P. Jaiswal Institute in Patna.

13. Pratapaditya Pal, “Some Nepali Bronzes in Bharat Kala Bhavan”, Chhavi, Vol. 1 edited by Anand Krishna, Banaras, 1971.

14. Guiseppe Tucci, Tibetan Painted Scrolls, 3 vols., Rome, 1949.

15. R.C. Sharma, Kamal Giri and Anjan Chakraverty, Indian Art Treasures: Suresh Neotia Collection, New Delhi, 2006.

16. See discussion in Pratapaditya Pal, The Arts of Nepal, II: Painting, Leiden, 1978, pp. 149, 153–54, and figs. 214–18, of which the dated painting of 1695 representing the cosmic form of Avalokiteshvara (lots 41 and 42) belongs to the Bharat Kala Bhavan.

17. I am grateful to Radhika Sabavala for providing the biographical information about her parents, to Anujit Gangoly for the image in Figure 6, to Jeff Walt of the Rubin Museum of Art, New York for the identification of the thanka in lot 67, Rivka Israel for style editing, to my assistant Nancy Rivera for her diligence in preparing the manuscript for this Introduction in record time, to Robin and Sonali Dean for the catalogue details, and to Edward Wilkinson for references.

Dr. Pratapaditya Pal Dr. Pratapaditya Pal is a world-renowned Asian art scholar. He was born in Bangladesh and grew up in Kolkata. He was educated at the universities of Calcutta and Cambridge (U.K.). In 1967, Dr. Pal moved to the U.S. and took a curatorial position as the 'Keeper of the Indian Collection' at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He has lived in the United States ever since. In 1970, he joined the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and worked there as the Senior Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art until retirement in 1995. He has also been Visiting Curator of Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art at the Art Institute of Chicago (1995–2003) and Fellow for Research at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena (1995–2005). Dr. Pal was General Editor of Marg from 1993 to 2012. He has written over 70 books on Asian art, whose titles include, Art of the Himalayas: Treasures from Nepal and Tibet (1992), The Peaceful Liberators: Jain Art from India (1994) and The Arts of Kashmir (2008). A regular contributor to Asianart.com among other journals at the age of 85+, Dr. Pal has just published a biography of Coomaraswamy titled: Quest for Coomaraswamy: A Life in the Arts (2020).

Download the PDF version of this article

Articles by Dr. Pratapaditya Pal

asianart.com | articles