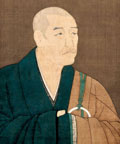

“As

I grow older, I have stopped having lush dreams,

Even one hibiscus tree by the pond is too much for me.”

—Su

Shi (Su Dongpo; 1037-1101)

Melancholic

crush of age, eloquently quantified in the words of Su Shi, Northern Song

dynasty poet, who distilled the siphon of tremulous beauty and grand aspiration

in two measured lines. With his Spartan denial of those chimerical yearnings

that ease the passage of time, the poet’s vital illusions fell away

with the rush of years. An unknown painter deftly captured Su Shi’s

metaphysical starkness, his reductive humanity and isolation in the face

of natural splendor, in Su Shi in a Straw Hat and Sandals (Japanese,

Muromachi period (1392-1573), before 1460), a scene from legend set late

in the scholar-official’s life when he was exiled for three harsh

years to an island off the coast of Guangdong Province—precipitating

his death. Ragged brush strokes speak of Su’s devastation, while

predatory ink conjures a bleak environment of palpable hostility, but

it is the painting’s deeply empathetic inscriptions by five Zen

monks that bring resonance to his tragedy.

Profound

dimensions of personal expression within the Zen pantheon are the cornerstone

of Awakenings: Zen Figure Painting in Medieval Japan, the wholly

sublime and ever fascinating exhibition at Japan Society in New York City,

fittingly mounted on the institution’s centennial anniversary. On

view from March 28-June 17, 2007, Awakenings is the first United States

museum exhibition in over thirty years to delve into the consequence and

genesis of figural painting in the implementation, operation, and continuation

of religious lineage in medieval Japanese (Zen) and Chinese (Chan) monastic

environments.

Fig.

2

Fig.

2 |

|

As a number

of pieces in the exhibition rarely travel or leave Japan, the gallery

space fairly radiates a rarified, hallowed aura, further heightened by

the presence of one Japanese National Treasure and eleven Important Cultural

Properties. The sheer sweep of history neutralizes any persistently anachronistic

thoughts of modern strife, and the metaphysical traveler is immersed.

Spanning the 13th through 16th centuries, forty-seven painted masterworks

impart flesh on legend, manifesting compelling representations of Bodhidharma,

(fig. 2) the Buddha Sakyamuni and assorted bodhisattvas, and the First

Patriarch of Chan/Zen within the microcosm of their immediate spheres,

as well as the macrocosm of communities without.

| |

Fig.

3

Fig.

3 |

In crafting

an innate understanding of the Zen world, and those who inhabited its

realms (fig. 3), the exhibition—co-organized by Japan Society and

the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan, and the Independent Administrative

Institution National Museum of Japan (Tokyo National Museum, Kyoto National

Museum, Nara National Museum and Kyushu National Museum)—excels

in conjuring an “ideal self”. Co-curators with great spiritual

sensitivity and a robust, vivid eye for the aesthetic eclecticism necessary

to successfully usher viewers of diverse backgrounds into this alien and

sacred space, Yukio Lippit, Assistant Professor, Department of the History

of Art & Architecture, Harvard University, and Gregory Levine, Associate

Professor, Department of History of Art, University of California, Berkeley,

have created rooms of profound contemplation. Dwelling in these constructed

monk’s cells, one not only senses an intense wave of connectivity

between the various works themselves, but also feels the vaporous trails

of myriad silent dialogues between visitors and individual paintings—the

encompassing vision and embodiment of the accrued knowledge of Yoshiaki

Shimizu, Professor of Japanese Art History, Princeton University, who

is Senior Advisor for Awakenings.

Fig.

4

Fig.

4 |

Fig.

5

Fig.

5 |

Fig.

6

Fig.

6 |

Fig.

7

Fig.

7 |

In presenting

those painted fusuma-e (sliding door panels) and wall scroll

paintings that best evoke Zen Buddhist monks in their spirit-infused states—sleeping,

dreaming, walking, and reaching awakening—the exhibition never fails

to elicit the unbridled individuality of both subject and artist. Animated

brushwork, inventive compositions, and resoundingly idiosyncratic visual

stylizations invoke a host of mythic personalities inhabiting striking

environs: the stark, graphic proportions and disarming intimacy of Muqi’s

Slumbering Budai (fig. 4); Kano Masanobu’s giddily rumpled

Hotei, hirsute icon and walking Mandlebrot Set, crafted from

a seemingly endless series of right angles (fig. 5); Kao’s The

Shrimp Eater (one of several equally enchanting crustacean devourers

on Japan Society’s gallery walls), reveling in its blasphemous delight

(fig. 6); the stunning transparency of Yue Hu’s White-Robed

Kannon, spun in calligraphic lines which pool liltingly before dissolving

into churning water (fig. 7).

Standing

alone in the third and final room of Awakenings, there is a place

where one can gaze out into the largest gallery space and see only blank

walls, a spot where not a single piece of art work is visible, and all

points converge on a moment of visual silence. A step in either direction

brings tantalizing vistas—serpentine folds on the garment of the

Fish-Basket Kannon (fig. 8), oceans that rear up with the ferocity

of dragons, the golden slippers of Shun’oku Myoha (fig.

9). But sometimes it is enough to step away from all that which is known,

to find a new face in the clouds. (fig. 10)

|