A Wondrous Great Accomplishment: a Painting of an Event *Preliminary findings and research for this paper were first presented at the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center Seminar in March 2010. My sincere gratitude goes to late Gene Smith and other scholars at TBRC who expressed great interest in the topic, enthusiastically offered their insights, comments, and provided additional Tibetan references and historical sources. A version of this paper was presented at the 12th International Association of Tibetan Studies Conference in Vancouver in August 2010.

by Elena Pakhoutova, Rubin Museum of Art

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions)

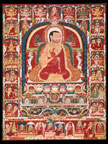

Fig. 1This article discusses a unique double-sided thang ka painting that depicts a series of fortunate events that took place during the construction and consecration of a stūpa at Gendüngang (dge ‘dun sgang) monastery in Central Tibet. One side of the painting shows a detailed process of the stūpa’s creation (fig. 1), the other side depicts the final structure completed and an elaborate ceremony of this stūpa’s consecration (fig. 2). The painting, in addition to the dual visual narratives on each painted side of the canvas, also employs another narrative mode, a literary or textual narrative. The side of the painting that depicts the building of the stūpa contains a large inscription rendered as a horizontal text panel.

Fig. 2This presentation briefly analyzes this painting's composition, its visual and textual contents within the broader cultural context but alongside specific historical, religious, and artistic comparisons and evaluations. This discussion will address general questions regarding relationships between text and image; the consecration ritual, the biographical genre and lineages in visual representations; as well as their interpretation with regard to this particular painting.

Fig. 3When we look at a painting depicting a stūpa we usually have various associations and think of different contexts within which the painting can be discussed and understood. The most immediate connotation for the stūpa is its relationship with the relics housed within, but what are the implications for the painted image of the stūpa (fig. 3). The symbolic meaning of a representation continues that of an actual subject, a physical object, or structure but it also adds a lot more and serves as a medium for further related associations and meanings that are conveyed and received.

One example of the complex relationship of the meanings inherent, intended, or constructed, as well as perceived in the paintings of stūpas is the well-known eight types of stūpas that symbolize and commemorate the eight great events from the life of the Buddha.[1For two early images of such representations from Khara-Khoto please see:

http://www.hermitagemuseum.org

For a later Tibetan example please see: http://imageserver.himalayanart.org

Please see footnote 1 at the bottom of this article for links to these images.] The Praises to the Eight Great Stūpas of the Buddha, the texts found in Tibetan and Chinese translations that identify these events, specifically focus on the events and their commemoration.[2Versions of the Praises can be found in all editions of the Tibetan canon, for example two texts in the Derge edition: 'Phag-pa-klu-sgrub/[Nāgārjuna], "Gnas chen po brgyad kyi mchod rten la bstod pa (Aṣṭamahāsthānacaityastotra) - Praise to the Eight Great Stūpas of the Eight Great Places [of the Buddha's Life]," in Bstan 'gyur bstod tshogs (Tibetan Tripitaka, Collection of Praises) (Derge edition), Ka, ff. 81v-83v] This is an important aspect of stūpa representations that is particularly relevant to the painting discussed here. The Praises to the Eight Great Stūpas of the Buddha also actively promoted making of the stūpas and images of the eight stūpas as means to accumulate a tremendous amount of merit and insure a good rebirth.[3For some English translations and initial interpretations of the praises please see: P.C. Bagchi, "The Eight Great Caityas and Their Cult," Indian Historical Quarterly 17 (1941); Hajime Nakamura, "The Aṣṭamahāsthānacaityastotra and the Chinese and Tibetan Versions of a Text Similar to It" (paper presented at the Indianisme et Buddhisme Mélanges offerts à Mgr. Ètienne Lamotte, Louvain-la Neuve, 1980).] This is another facet of the composite meanings of these visual representations of stūpas.

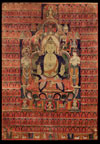

A stūpa is also often depicted as an inherent feature of representations of the deity Uṣṇīṣavijaya, or Tsuktor Namgyalma in Tibetan (gtsug tor rnam rgyal ma) (fig. 4a). In this context the traditional symbolism of the stūpa is integrated into the consecratory, purificatory, and the long life aspects of the complex ritual meanings of Uṣṇīṣavijaya’s iconography. Direct references to this will be evident in the discussion of the painting in question.

Fig. 4a |

Fig. 4b |

Fig. 5a |

Fig. 5b |

Another example of such continuation and expansion of the meanings, especially in the context of paintings and stūpas is that of stūpa images on the reverse of the paintings. In these instances they literally represent the Dharmakāya and serve as a consecration symbol, containing within its outline either the Verse on Interdependent Origination, dhāraṇī, mantras (fig. 4b; fig. 5a, b), and short passages from sūtras, such as the Verses on Patience, found for instance in the Sūtras on Individual Liberation (Prātimokṣa) (fig. 6a, b); (fig. 7a, b);[4"So sor thar pa'i mdo (Pratimokṣa Sūtra; Sūtra on Individual Liberation)," in Tibetan Tripitaka: Kangyur, 5 (Derge edition), 20a4. Such inscriptions are also discussed in Dan Martin, "Painters, Patrons and Paintings of Patrons in Early Tibetan Art," in Embodying Wisdom: Art, Text and Interpretation in the History of Esoteric Buddhism, ed. Rob Linrothe and Henrick Sørensen (Copenhagen: The Seminar for Buddhist Studies, 2001), 139-184.] as well as verses of praise/evocation and biographical passages related to the main subject of the painting.[5A few interesting examples of such inscriptions were presented by Andrew Quintman, "Biographical Relics in the Consecration of Tibetan Portraiture," in Conference of the Association for Asian Studies, Panel on Himalayan and Central Asian Art and Culture (Chicago: 2009). A version of this paper is due to appear as "Life-Writing as Literary Relic: Image, Inscription, and Consecration in Tibetan Biography," Material Religion (2012). ] Even when the text is minimal and reduced to the three syllables “Oṃ Ah Huṃ,” or absent all together, the image of the stūpa drawn in thin line continues to serve as a consecration symbol for the subject painted on the front of the thangka (fig. 8a, b).

Fig. 6a |

Fig. 6b |

Fig. 7a |

Fig. 7b |

Fig. 8a |

Fig. 8b |

In yet another cultural context, images of famous stūpas at pilgrimage and sacred sites invoke stories of their construction or their miraculous origination. Visual narratives of communal festivals at the sites emphasize the sacredness of the site and serve as a record of the event, assuring at the same time further accumulation of great merit by the patron of the event, commissioner of the painting and all involved, including those viewing the painting as well. One of the examples of these practices is the painting currently in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts depicting the re-consecration of the great stūpa of Svayambhu in Kathmandu that was performed in 1565.[6For the image of the painting, please see figure 1 in the recent publication on the latest Svayambhu renovations: Dina Bangdel, "Visual Histories of Svayambhu Mahacaitya," in Light of the Valley: Renewing the Sacred Art and Traditions of Svayambhu, ed. Tsering Palmo Gellek and Padma Dorje Maitland (Cazadero, CA: Dharma Publishing, 2011).] It is important to note that the Nepalese painting commemorates the event and shows not only the stūpa, but also numerous people who were involved in this communal enterprise. This aspect of visual documentation of the event is also relevant to the discussion of the double-sided thangka.

Examining the Painting and the Inscription

Let's examine the painting at hand alongside the inscription and contemplate on the content of the whole, bearing in mind the contextual framework outlined above.

Fig. 9A logical start is the process of the stūpa’s construction, so we start with the de-facto “verso” of the painting. The construction really begins with laying down the foundation for the structure. Before the digging, the ground consecration is performed, the actual foundation is built and so on. The painting shows various groups of very animated people evidently looking at a wondrous rainbow-colored sphere connected to the ground consecration maṇḍala by the “ribbons” of lights that wrap around the central axis of the stūpa (fig. 1). We also see particular tasks performed by teams of people - some are digging the ground (fig. 9: detail of fig. 1), others are making clay bricks (fig. 10: detail of fig. 1), others are then carrying them up the stūpa’s structure (fig. 11: detail of fig. 1). There are people performing rituals, some of them have implements in their hands while others have them displayed in front on tables (fig. 10: detail of fig. 1). Groups of lay people are shown as most amazed by the miraculous display (fig. 12: detail of fig. 1).

Fig. 10 |

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 12 |

The text gives the same account, but in a less vivid manner and without the details found in the visual rendering of the occurrences. It says:

At the glorious monastery of Gendüngang, in the year of the male metal rat (1360), from the fifth day of the third month [was] performed the ground ritual; from the eighth day the foundation’s sanctum (or chamber, rman ting) was made; and all the monks, as a great gathering performed the vast mantra accumulation as well.

The inscription actually starts with homage to the teacher (bla ma), the lord of the Dharma and all knowing, and is preceded by the traditional “Oṃ Swasti.” Then the text continues:

At the arrival to Tibet of the Kashmiri Śakya ṣrībhadra, who is the great pure monk uncontested in India and Tibet, a community of monks who observed the discipline of eating only once a day was established.[7The History of Vinaya by Tsechogling Yondzin (Tshe mchog glin Yons ‘dzin Ye shes rgyal mtshan, 1713 - 1793) gives an account of the four main establishments founded by Śakyaṣrī’s two main students and corroborates the fact that these communities were indeed observing taking food once a day. For example: “198.4: tshul bzhin du slob pa'i dge 'dun gyi sdegang 'phel byas te sten gcig gi bstul zhugs 'dzin pa'i dge slong gi sde mang du 'phel te rim gyis thsogs sde bzhir grags pa jobo stan gcig pa zhes snyan pa'i grags pas phyogs.” Translation: Monastic communities who observed the discipline of eating only once a day expanded. Gradually these known as "the Four Monastic Communities of Elders [who] eat once," became renown and spread all over. See Tshe-mchog-glin-Yons-‘dzin-Ye-shes-rgyal-mtshan, "Rgyal ba’i bstan pa’i nang mdzod dam pa’i chos ‘dul ba’i byung tshul brjod pa rgyal bstan rin po che’i gsal byed nyin mor byed pa’i snang ba," in Collected Works, (gsung 'bum) (New Delhi: Tibet House, 1975), 6, 198.4.] The student of Śakyaṣrī’s direct disciple Changchub Pal and the nephew of Khenchen Tsangpa (mkhan chen gtsang pa dbang phyug grags (13th-14thc.) was an arhat (dgra bcom pa) Zhonnu Changchub (gzhon nu byang chub, (1279-1358?).

This master is a known abbot of Gengüngang monastery, one of the four main monastic establishments founded by Śakya ṣrībhadra’s direct disciples that were also the sources of monastic ordination lineages in Tibet. Zhonnu Changchub is named as the Third abbot in the abbatial succession in the Blue Annals[8Gos-lo-tsa-ba-Gzhon-nu-dpal and George Roerich, The Blue Annals, 2d ed. (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1976), 1072-1073.] and as the Second abbot in the Yarlung Jowo’s History of the Teachings (Yar lung jo bo’i chos ‘byung, composed by Shākya Rin chen sde, 14th century). The latter text lists the abbots of Gengungang and says that after Tsangpa (gtsang pa, dbyang byub dpal’s student) was his nephew Zhon Jyang (gzhon byang, or gzhon nu byang chub) who is the main subject of the painting’s inscription. After him his nephew Dültsepa ('dul tshad pa byang chub bzang po) was the next abbot. Next was Yonten Gyaltsen (mkhan po yon tan rgyal mtshan, active in 14th century), the master who presided over the ceremonies described in this inscription and shown on the thangka.[9Shakya-rin-chen-sde, Yar Lung Jo Bo'i Chos 'Byung (Lhasa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skun khang, 1988), 172. This list misses one of the abbots mentioned in the Blue Annals, Jamyang Dondrub Pal ('jam dbyangs don grub dpal) and goes straight to Yonten Gyaltsen (yon tan rgyal mtshan), who is listed as abbot number six in the Blue Annals. This history, written in the late 14th century (?) ends the abbatial succession on the seventh abbot, Pal Drubpa (dpal grub pa) naming him as the present abbot. It also states that monastic communities of Cholung and Gendüngang, both have the ordination lineage coming from the abbot Changchub Pal (byang chub dpal), the direct disciple of Śakyaṣrī.]

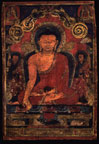

The upper section of the other side of the painting shows Śākyamuni and teachers of the Gendüngang’s ordination lineage beginning with Śakya ṣrī; Zhonnu Changchub, his teacher Changchub Pal (byang chub dpal) and other three masters (fig. 13, below: detail of fig. 2).[10The images are not inscribed. Notable that one monk figure among the four shown around the central figure of Zhonnu Changchub on the lotus above the stūpa does not have a halo (top right).] Besides the buddhas of the past, present and future (seven in total, three on each side of Śākyamuni) there are also portraits of the great Indian philosophers, Buddhist masters known as “the six ornaments of Jambudvipa,” who are shown on separate clouds, three on each side in the upper corners of the painting.[11They are Vasubandhu, Asanga, Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Dignaga, and Dharmakirti.]

The text panel goes on to briefly outline the life of Zhonnu Changchub:

{2} He was born in the year of the female water hare[12The year 1243, female water hare, doesn’t work as the year of his birth when counted according to the inscriptions’ date of his death. He was probably born in the year of the earth hare, 1279, which fits with the rest of the dates mentioned in the inscription.] and gradually became the lamp of the Dharma; learned the Tripitaka; achieved the end results of the Three Instructions, perfected the Three Vows| With the three [aspects of] knowledge, [teaching, and meditation (?)] [he] brought about inconceivable benefits to others and himself; held the seat of the monastery for [fifty] four years, acted as [ordination] abbot and teacher [to] Lama Tishri Kunga Lodro (bla ma tishri kun dga’ blo gro, 13th - 14th c.), Dharma Lord Ranjung [Dorje] (chos rje rang byung rdo rje, 1284-1339)[13The biography of the Third Karmapa Ranjung Dorje (1284-1339) mentions that he was ordained at the age of nineteen at Sangphu, a Kadampa monastery by the abbot Śakya Zhonnu. This seems to contradict this inscription but it is possible that Śakya Zhonnu is the same person as Chang chub Zhonnu of the inscription who may have been the abbot of Sangpu and later became the abbot of Gendüngang. It is also possible that these two abbots Śakya Zhonnu and Changchub Zhonnu are two individuals who held the same ordination lineage that stemmed from Śakya Śrī and his direct disciples.] and others;

{3} and all the great [masters] of Ü Tsang [region]. In short this [master], who became a pure crown ornament of all the doctrine holders, showed [the appearance of] passing away at the age of eighty in the year of the fire female bird (1358). In consideration of his kindness Khenchen Yonten Gyaltsen (yon tan rgyal mtshan, 14th c., the Sixth abbot of Gendüngang) expressed an intention to erect his stūpa|

Fig. 13Then the text refers to the other side of the painting and the beginning of the construction and goes on to give a brief discourse related to the original creation of the Uṣnīshavijaya stūpa telling the story of a god called Nirmala who asked the Buddha how to remedy his impending unfortunate low rebirth. Nirmala took refuge and the Buddha gave a discourse on building the stūpa of immaculate Uṣnīṣa. The god’s negativities were purified and his life prolonged.

The text then references the rituals that were performed during this stūpa’s construction and describes the miraculous events that accompanied them:

{5} ... When talking about the benefits of [this] story, rituals, similarly as to how Lhenkye Rölpa (lhan skye rol pa, Padmasambhava) and pandita

{6} Śantarakṣita made dhāraṇī and tsa tsa of the stūpa of immaculate Uṣníṣa, [and] according to the ritual practice of Tulku Butön,[14This refers to Büton Rinpoche (Bu ston, 1299-1364), the famous scholar and compiler of the Tibetan canon, who was also known to hold the ordination lineage that originated at Gendüngang monastery. Khongtrul in his Shes Bya Kun Khyab says that the ordination lineages from Gendüngang have been received by all knowing (thams cad mkhyen pa) Karmapa Ranjung Dorje (1284-1339), Ngor chen (1382-1456) and that these are the so-called kar lugs and sa lugs that were known at his time. They were further spread through the Great Fifth. See Kong-sprul-Blo-gros-mtha-yas, in Theg pa'i sgo kun las btus pa gsung rab rin po che'i mdzod bslab pa gsum legs par ston pa'i bstan bcos shes bya kun khyab, ed. Rdo-rje-rgyal-po, et al. (Peking: Mi rigs dpe skun khang, 2002), 1, 222.] on the thirteenth of the fourth month, the lama’s remains (body), ordinary supports, tsa tsa were excellently established. To the west of the foundational bowl a rainbow appeared [but] all the outsiders did not see it |

{7} and; also at the time when Gungtangpa Lopön Lobsang was tending to ashes, in the center of the urn emerged innumerable relics, and when they were gathered [there] appeared many special visions; at dawn of the twenty eighth when the Khenchen Yon[ten] Gyal[tsen] have taken [the lama’s] own statue (?), facial hair, and other extraordinary objects of veneration to place [them] in a dome of the stūpa

Fig. 14{8} at the beginning something like a ribbon attached to the tip of a crystal vajra came from the sky and dissolved into the stūpa’s dome | from the maṇḍala of Immaculate [Uṣnīṣa] flew [out] a ball of light and dissolved into the dome. [This] was seen by one fully ordained monk of Drongbu (‘brong bu, place) ; then all saw five-colored light coming out from the central axis [of the stūpa], from it rainbow clouds and light filled up the sky (fig. 14);

{9} great rain of flowers fell | some experienced seeing a precious jewel, crossed Source of Reality (two crossed triangles) and so forth appearing from Oṃ, many various visions and appearances happened, all [at the time of] supplication(?) [there was] ... sound of laughter, and many also generated the state of meditative contemplation (samadhi) and the Mind of Enlightenment (bodhicitta) ; in short it turned into wondrous great delight [experienced by all] in some measure ||

It is notable that the text refers to both pictorial narratives alternating between the two sides of the painting. To grasp the whole story we have to read the textual narrative and to follow the visual narratives on both side of the canvas. All the masters involved in the consecration rituals mentioned in the text are depicted on the side of the painting that shows the stūpa complete. The text, however, being on the other side of the painting concludes, saying:

{10} on the sixth of the fifth month, on the east Khenchen Yon[ten] Gyal[tsen] [established] Vajradhatu, on the south lama Lhung Lhepa (lhung lhas pa) [made] its fire offering ritual and at North Lama Zhonnu Dar ([mthar rtsa’i] bla ma gzhon nu dar) performed the Vajrabhairava [maṇḍala ritual] ; Master Jetsüngpa (rje btsun pa, Gungtangpa Lopën Lobsang mentioned above) perfectly performed the consecration ritual of Vairochana (? unclear). On the eleventh day at dawn, the fire [of the fire ritual] was dispelled; up to that point rainbows were appearing without interruption [Thus ends this] partially completed [account].

Fig. 15 |

Fig. 16 |

Fig. 17 |

Fig. 18 |

The front of the painting shows the stūpa completed and surrounded by the four mandalas of the performed rituals. At the bottom left is East, SarvadurgatipariŚodana, the rituals and maṇḍala consecration performed by Yonten Gyaltsen (fig. 15: details of fig. 2). At the top left is South, where the Fire ritual was performed by Lama Lhung Lhepa (fig. 16: detail of fig. 2). At the lower right is North, where the Bhairava (Yamantaka) was performed by Lama Zhonnu Dar and at the top right is West (not mentioned as the direction in the text), where the Vairochana (?) maṇḍala was created (fig. 17: detail of fig. 2). Right below the stūpa is the maṇḍala of the ground consecration (fig. 18: detail of fig. 2), the same as shown on the other side of the painting when the stūpa is under construction.

Fig. 19This concludes the narratives of the event, the construction and consecration of the stūpa in honor of the abbot Zhonnu Changchub, but the story of the painting is not complete. A portrait of the Tibetan monk donor in the lower left corner of the painting (fig. 19: detail of fig. 2), not identified by inscription raises questions related to the purpose of this painting’s creation and dating. Additional comparative stūpa images suggest that the painting could have been created shortly after the consecration of the stūpa, or in late 14th century. Butön’s manual on stūpa construction and his study of the typology of the stūpas was completed somewhere around the mid-14th century.[15Bu-ston-rin-chen-grub, "Byang chub chen po'i mchod rten gyi tsad: Measurements for the Stūpa of Great Enlightenment," in The Collected Works of Bu-Ston (New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture, 1965), vol.14, 551-558.] Murals at Zhalu monastery even at present provide the testimony of the uniformity of the Tibetan stūpa types, which are based on the Uṣnīṣavijaya stūpa specifications (fig. 20).

Fig. 20There are evident similarities between these two painted images of stūpas and it is possible to suggest that they could have been painted not very far apart in time. It would also make sense that the main patron of the event, the Sixth Abbot of Gengüngang monastery Yonten Gyaltsen (active in the 14th to early 15th century) was also the patron of the painting that documented the event.[16This suggestion was strongly encouraged and favored by Gene Smith at the time of the initial presentations of this research.] When considering the five teachers’ figures around the image of Zhonnu Changchub in the upper central section of the painting under the figure of the Buddha (fig. 13), Yonten Gyaltsen’s sixth’ place in the abbatial succession makes it another plausible supportive argument to this supposition. He would indeed be the donor depicted in the lower left corner of the painting (fig. 19) whereas his predecessors, the five abbots and Śākya Śrī bhadra occupy the honorable position in the upper part of the painting where lineage masters are usually depicted. This assumption is also indirectly corroborated by the fact that in the 16th-century visual documentation of the re-consecration of Svayambhu stūpa the donor of the painting and the patron of the event shown in the painting are the same and the painting was produced at the same time the event took place.

Another alternative possibility could be that the stūpa at Gendüngang was renewed sometime later and the painting was created at the time of this later renovation. In this scenario, it may be possible that the donor shown in the painting is a student of Yonten Gyaltsen, the main patron of the stūpa’s construction. However, in my view this then would require some additional textual reference, which is absent in the text panel. The text gives only a brief overview of Zhonnu Changchub’s life, states the main patron’s (Yonten Gyaltsen’s) intentions, and describes the events as presented above. There is no colophon identifying the scribe or the author of the text, nor there is any reference to the place where the painting and the text were produced. The nature of the textual narrative overall is not biographical but rather directly illustrative of the pictorial narratives shown on both sides of the canvas.

Concluding remarks

It is evident that this painting is quite distinct from known lineage paintings, depictions of stūpas, consecrational images, even historical and narrative paintings, which were mentioned in the contexts of painted images of stūpas earlier. This painting, as it was shown, does not portray the live of Zhonnu Changchub but shows what happened on this particular occasion that was apparently important to the monastic community at Gendüngang monastery and to the person who commissioned the painting. The visual as well as written details of this painting notably reflect the actuality that building of the stūpa is an enormous undertaking that requires a collective effort. During this time period (14th-15th centuries) especially, great many stūpas were built in Ü and Tsang. Almost most of these structures ultimately promoted specific lineages. Miracles and their expectations were another integral part of such communal and public enterprises.[17For examples and implications of various miraculous occurrences, please see Dan Martin, "Crystals and Images from Bodies, Hearts and Tongues from Fire: Points of Relic Controversy from Tibetan History," in Tibetan Studies: Proceesings of the 5th Sminar of the International Assiation for Tibetan Studies, ed. Ihara Shören, et al. (Narita: Narita Shinshoji, 1992), 1, 183-191.] There are numerous accounts of miraculous occurrences during the stūpas’ consecrations recorded in teachers’ biographies, historical writings and monastic registries. This painting provides a unique perspective, if you will, for the extensive stūpa construction activities that took place in central Tibet from the late 14th century onwards.

This exceptional thang ka presents a special opportunity to study a rare confluence of cultural practices that involve creative expressions of commemoration centered on important occurrences within monastic lineages, adding to the known methods of visual and historical documentation.

Considering that Gendüngang monastery, founded in 1225 as one of the four monastic centers established by the great Kashmiri pandita Śākya Śrī bhadra (1127-1225), is still one of the less documented in both historical accounts and art, this painting is a rare example of its recorded communal history. Expressed in the two complementary modes of visual and literary narratives centered around the commemorative stūpa of the Third abbot Zhonnu Changchub the painting possibly reflects a deliberate later recollection, on the part of its donor, of the monastery’s one glorious moment.