Ghosts, Demons and Spirits in Japanese Lore

by Norman A. Rubin

June 26, 2000

(click on the small image for full screen image with caption)

Belief in ghosts, demons and spirits has been deep-rooted in Japanese folklore throughout history. It is entwined with mythology and superstition derived from Japanese Shinto, as well as Buddhism and Taoism brought to Japan from China and India. Stories and legends, combined with mythology, have been collected over the years by various cultures of the world, both past and present. Folklore has evolved in order to explain or rationalize various natural events. Inexplicable phenomena arouse a fear in humankind, because there is no way for us to anticipate them or to understand their origins.

Fig. 1 The mystery of death is a phenomena that does not offer a rational explanation to

various cultures. Death is an intruder. Death is the change from one state to another, the

reunion of body with earth, of soul with spirit. Humans, throughout the ages, have seldom

been able to believe or to understand the finality of death. For this reason fables and

legends have evolved around the spirits of the dead.

The Japanese believe that they are surrounded by spirits all the time. According to the Japanese Shinto faith, after death a human being becomes a spirit, sometimes a deity. It is believed that eight million deities inhabit the heavens and the earth - the mountains, the forests, the seas, and the very air that is breathed. Traditions tell us that these deities have two souls: one gentle (nigi-mi-tama), and the other violent (ara-mi-tama).

Buddhism, which was introduced into Japan in the sixth century CE, added a new dimension to the belief in spirits and other supernatural forces. The Buddhist belief in the world of the living, the world of the dead, and the ‘Pure Land of Buddha’ (Jodo)1 achieved a new meaning. The way a man behaved during his lifetime determined whether he would go to the world of the dead or the ‘Pure Land’. Those driven to the nether-world found it to be a hell in all its vileness.

The Japanese believe that after death a spirit is angry and impure. Many rituals are performed for seven years to purify and pacify the soul. In this way the person becomes a spirit. According to belief, a spirit wanders between the land of the living and the world of shadows. For this reason, prayers are offered to insure passage to the Land of the Dead.

Ghosts (Yurei)

If the soul of the dead is not purified, it can return to the land of the living in the guise of a ghost. Also, if a dead person is not delivered, through prayer, from personal emotions such as jealousy, envy or anger, the spirit can return in a ghostly guise. The ghost haunts the place where it lived and persecutes those responsible for his or her bitter fate. The ghost will remain until released from its suffering through the good offices of a living person who prays that the soul of the dead may ascend.

During the Heian era (794-1185) it was believed that ghostly spirits floated above the living causing disease, plague and hunger. In the Kamakura era (1185-1333) a belief was reinforced that spirits turned into small animals, such as raccoons and foxes, that led people astray. Household objects, when a hundred years old, could become deities in the Muromachi period (1336-1573). These venerable objects were thought to possess special powers and were treated with care and respect. And in the Momoyama (1573-1600) and the Edo periods (1603-1868) there was a belief that if a man died of disease or in an epidemic, he turned into a monstrous demon.

The despotic feudal regime which prevailed during the Edo period, combined with natural disasters that occurred at that time, added to the lore of evil and vengeful spirits and ghosts. At the close of the Edo era, edicts were passed forbidding the display of theatrical performances with the theme of frightening ghostly spirits, for fear of undermining the government.

Most creatures in stories of unfortunate spirits were women. They were vengeful ghosts, and the greater the misery endured by the woman during her lifetime, the more threatening her ghostly spirits would be after her death. Cruelty to women is a recurring theme in Japanese lore and legend.

Ghost stories were dramatized for puppet theaters in the early1700’s. Ghost stories then began to be enacted in various theaters including Sumizu theater of Osaka and Nakamura-za theater in Edo.

Fig. 2Vengeful spirits became the central theme in the Kabuki theater at the end of the

18th century. Murder was presented on the stage in all its gory details, and

female ghosts were distinctly portrayed. The scenes of crime and bloodshed presented were

shocking and intended to arouse suspense and fear. Surprisingly, these plays were quite

popular, and print artists reproduced many scenes of these Kabuki productions. An example

of this theme is in one of the plays enacted at the Kabuki theater called the ‘The

Rock That Weeps at Night.”

“At Tokaido, on the road between Tokyo and Kyoto, there is a famous rock known as ‘The Rocks that Weeps at Night’. Lore tells of a pregnant woman travelling along this road at night to meet her husband. Bandits accosted her and she was barbarously murdered. Her blood spilled onto the rock, which became the habitation of her ghost. Legend has it that the rock weeps at night.” 2

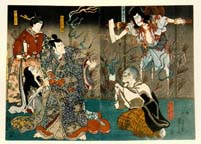

Fig. 3Demons in Japanese lore wander between the living and the dead. Sometimes demons do

good deeds in the world, and sometimes they wreck havoc. Demons have supernatural powers;

but they also have the magical ability to affect natural phenomena. According to Japanese

belief, some demons are the root of all disasters, both natural and man-made.

Japanese demons are not altogether evil but are also tricksters and enjoy playing practical jokes. In the Edo period they began to depict the demons with humour, especially in Netsuke figures 3. This was a way in which the people equated the demons with the upper classes; also this was a way to mock the heavy-handed feudal rule.

Ceremonies, known as the ‘Oni-Yari’ or ‘Tsuina’, are performed to exorcise demons. These rites are usually conducted at the last night of the year in the Emperor’s Palace: The ritual is comprised of people throwing roasted soy beans in the four directions and calling out, “Enter, good fortune, demons depart!” The fear of pain causes the demons to run away.

The Oni

In folklore there are also tales of supernatural creatures called the ‘Oni’. Artists depict the ‘Oni’ with horns and wearing tiger skins. They have no neck, but a crest of hair and a big mouth; their fingers are clawed, and their arms elevated to the shoulders. These artistic renditions of demons not only represent the supernatural, but also embodiments of the evil facets of human nature. The earth ‘Oni’, according to Buddhist belief, are responsible for disease and epidemics (they are dressed in red). The ‘Oni’ of hell (red or green bodies) hunt for sinners and taking them by chariot to Emma-Hoo, the god of hell. There are invisible demons among the ‘Oni’ whose presence can be detected because they sing or whistle. The ‘Oni’ who are women are those transformed into demons after death by jealousy or violent grief. The Buddhist ‘Oni’ demons did not always represent the forces of evil.In Buddhist lore there are tales of monks who after death became ‘Oni’ in order to protect temples from potential disasters. The belief in the ‘Oni’, reached its zenith in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Tengu - The Mountain Demon

Another prominent demon in Japanese folklore is the ‘Tengu’, a mythological being living in mountain forests. Artistic depictions of the ‘Tengu’ range from stumpy, bearded creatures to beings with great lumpy noses. According to lore, anyone entering the territory of the ‘Tengu’ unwittingly can fall into strange and unpleasant situations. The ‘Tengu’ can, in a flash, transform themselves into ugly little men, women and children; then they maliciously tease people with all sorts of nasty tricks. As quickly as they appear, just as quickly they vanish. Some ancient beliefs depicted the ‘Tengu’ as creatures of war and conflict. Sometimes their actions in legends are hypocritical. Artists depicted them with a bird’s head on a human body with spreading wings and clawed feet. Until the 14th century, evil legends were told about the ‘Tengu’; but gradually they evolved into both good and bad beings. Many tales were told of the ‘Tengu’ overcoming evil. In the Buddhist belief they became guides for monks in understanding the Dharma tenets and sacred rites, and also protected Buddhist shrines.In the 18th and 19th centuries they were revered as mountain deities- tributes were offered to them. The woodcutters and huntsmen offered tributes to the ‘Tengu’ deities in order to receive success in their work.

Those that were less respectful found themselves in all sorts of trouble. The belief in the ‘Tengu’ continued until the beginning of the 20th century. Today ceremonial festivals are held in their honour. Tales are still being told of them in modern Japan. In some areas, woodsmen still offer rice cakes to the ‘Tengu’ before starting their work.

ANIMALS WITH SUPERNATURAL POWERS

According to legend certain animals are created with supernatural powers. They can transform themselves into anything they desire, and can even acquire other magical abilities. The Japanese raccoon (tanuki) and the fox (kitsune) are the most popular animals attributed with magical powers. They have similar roles in folklore. They are pictured as mischievous rogues who often get themselves into trouble. They can, at times, be frightening creatures, and at other moments be capable of making a negative situation positive. Sometimes they are treated as godly figures and become cultural heroes. The ‘tanuki’ is sometimes seen as a witch, a cannibal monk, or a one-eyed demon who murders his victims with thunder, lightning or earthquakes.

The ‘tanuki’ is a small hairy animal, and it is believed that he can transform into a frightening creature. Sometimes he is depicted humourously, having a gigantic scrotum which he drags behind him or wears it as a kimono. In some Netsuke figures the ‘tanuki’ appears as a Buddhist monk dressed in robes and banging on his scrotum as if it were a temple drum. “There is a fable that tells of an incident by the abbot of the Morinji Temple. He bought a tea-kettle and instructed one of the monks to clean it. Suddenly a voice spoke from the kettle, ‘Ow that hurts, please be more gentle.’ When the abbot wanted to boil some water, out popped the tail, legs and arms of a ‘tanuki’ and the vessel started to run about the room. It dumbfounded the poor abbot and he tried to catch the kettle, but it eluded him.”

The fox (kitsune) is frequently a subject in Netsuke figurines. Many strange and uncanny qualities are attributed to the fox. The‘kitsune’ have the ability to change their shape, but their faces remain fox-like. In folklore, foxes pretend to be humans in order to lead men astray.

A black fox is good luck, a white fox calamity; three foxes together portend disaster. Buddhist legend tells of 'kitsune’ who disguise themselves as nuns, and wear traditional robes (depicted in Netsuke figurines). Fables tell how the fox likes to appear as women. Stories tell that while the ‘kitsune’ is in such a guise, he goes about tricking and misleading men into seduction. When the seduced come to the realisation of the true identity of their supposed love, the fox disappears. Legends tell of how ‘Kitsune’ can hypnotize people and lead them into perilous situations. To do this, according to the tales, they illuminate the path leading to such disasters, and this illumination is known as a ‘foxflare’ (kitsune bi).

Dragons and Snakes

In Japanese legend there are tales that depict snakes and dragons with supernatural powers. In ancient Japan the people believed in the snake-god ‘Orochi’, who lived on the very top of mountains. The Buddhist religion told of the dragon-god ‘Ryu’ who ruled the clouds, the rain, and the water. There was the dragon ‘Yasha’, one of the demon-gods who protected Buddhism. All these deities have wide mouths, sharp fangs, pointed horns, and all-seeing eyes.

Fig. 4In Japanese folklore there are tales told of people who turned into snakes after

death because of their evil ways and their miserly habits. A male becomes a serpent

because his desires are not satisfied in life. A female snake appears as an attractive

woman who marries a human: if rejected by her lover, her jealously will cause disaster.

Women are often associated with snakes because of tales told of them being fierce and

possessive towards their lovers. Children born of the union of a snake with a human may

either appear as a serpent or as a human with snake-like qualities. They appear in the

dreams of their family and friends, asking them to pray for the release of their souls

from their snake-like bodies. The relative either reads a Buddhist sutra or recites

special prayers. Then the soul is saved and the snake-body is shed. Some people are reborn

in the guise of snakes after death when they wish to avenge wrongful deeds. The

avenger’s ghost in Japanese lore is usually considered heroic. Snakes were not always

thought of as symbols of evil, but also of love with no bounds. “Long ago in Keicho

era, there lived a beautiful girl in Senju in the province of Musashi. A bachelor called

Yaichiro fell in love with her and sent her many missives of love to her; but she did not

respond. Yaichiro died of sorrow, and the girl married someone else. On the morning after

the wedding, the couple didn’t emerge from their room. When the bride’s mother

entered, she found the bridegroom dead, and a snake crawling out of one of the

bride’s eyes. The villagers believed that the snake was none other than the

heartbroken Yaichiro.”

Serpents and dragons are also associated with nature. Natural disasters, especially floods, are linked to them. It is believed that after storms they are washed out of their dens and come into the open. This is why they are believed to be producers of storms and surrounders of waters- both water-controlling and water-granting. There are four types of dragons in Japanese mythology: the heavenly dragons who guard the palace of the gods, the spiritual dragons who bring the blessed rain, the earth dragons who determine the course of rivers, and the dragons who are the guardians of all earthly treasures. In many paintings, artists depict the dragon as the ruler of the waters, the ocean and the rain.

Immortals and Heroes

The notion of immortality told in Japanese folklore is derived from Chinese Taoism based on the ideas of the philosopher Lao-Tsu in the fourth century BC. Even though Taoism never became an official religion in Japan, the Taoist creed appears in their literature and art. Those who achieved immortality could fly, walk on clouds, and pass through water unharmed. They were considered guardians of Taoism and protectors of humankind. The peach4 is the symbol of immortality and many netsuke figurines are depicted with this fruit. Immortals are also depicted carrying a three-legged frog, or pictured riding on a giant carp5 or a horse. The most famous of the immortals are the ‘Sennin’, the eight Taoist immortals. They are seen in art and netsuke figures breathing out their souls via their breath, wearing the robes of Taoist sages, or carrying gourds.6

Fig. 5Subjugating a demon is a favourite theme in the famous tales of warrior heroes. The

legend of the ‘Four Samurai of Minamoto no Yorimitsu’ conquering monsters and

demons in their citadel is a well-loved theme. Another favourite is ‘The Warrior

Watanabe no Tsuna’ fighting the Demoness of Rashomon.Another prominent fighter of

demons is ‘Shoki’, the exorcist of devils and evil spirits. He was a giant of a

man with great strength. ‘Shoki’ is usually depicted in art striding from left

to right after a unseen demon. He is usually coloured red, because it is believed that

this colour has the power to ward off misfortune. In the Kansei era (1789-1800), long

banners (nobori) were hung outside houses inhabited by small children. These banners were

sometimes decorated with ‘Shoki’, the exorcist, to repel demons and evil

spirits. Today in Japan they have begun to connect ‘Shoki’ with the Boy’s

festival, held on May 5th. In the past periods, this was believed to be the day

on which demons appear, and evil spirits and ghosts bringing misfortune. In order to avert

troubles on that day, ceremonies were conducted to drive away these poisonous creatures.

Fables and legends sustained these beliefs through art- in the form of drawings, paintings, prints, sculpture, ornaments, and words. Plays with ghostly and spiritual themes are still being performed in theaters throughout Japan. Scenes recreate the lore and mysticism of the spirits of the dead. The authors of such dramas combine fact with fiction, violence and bloodshed, and the classic tension between the tormented and the tormentor. These productions create a sense of fear and suspense among the audience, much to their delight. Even today, tales of ghosts, demons and spirits are presented on television and in cinema.