SKETCHING LEGACY: Korean Portraiture

at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

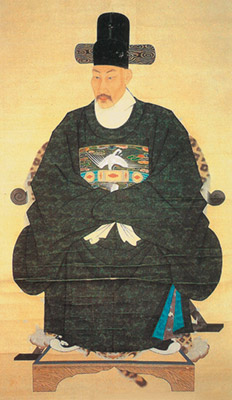

HYONJEONG KIM HAN“If one hair of a sitter is not rendered correctly, it is not the portrait of the sitter.” This Korean saying reveals that the most important requirement of great portraiture is the realistic portrayal of a sitter. During the Joseon dynasty (1392– 1910), painters went even further to convey the sitters’ spirits, beliefs, and sensibilities in the portraits. Portrait painters strove to follow the golden principle of “transmitting spirit through a depiction of outer appearance” established by a Chinese painter, Gu Kaizhi (approx. 344–406). Embedding essential characteristics and virtues of the subjects of portraiture was as crucial as realistically depicting their physical appearances.

The rise of Confucianism motivated portrait painters of the Joseon dynasty to capture their sitters’ inner spirits and personalities. In contrast with the previous dynasty, Goryeo (918–1392), which observed Buddhism as the state religion, Joseon adopted neo-Confucianism as its state ideology. Among the many values of Confucianism, people prioritized worshipping ancestors, maintaining family lineages, and performing numerous proper rituals. Portraiture was essential to carrying out these values. Various kinds of portraits in the Joseon dynasty included images of kings, royal families, officials, scholars, and religious figures. (Women were rarely portrayed in the period, and it was only in the nineteenth century that women, especially “beauties,” idealized young women of various backgrounds, began to be painted in portrait formats.) Portraits of members of royal families, meritorious officials, and scholars were kept in the appropriate portrait halls when not being displayed for royal or family ceremonies.

Loyalty is one of the most important virtues in Confucian society. Recognizing and awarding loyal meritorious officials began with the founding of the Joseon dynasty. Joseon kings appointed twenty-eight groups of meritorious subjects. Those appointed were considered courageous and intelligent officials who strengthened their kings’ power and the nation’s stability, especially in times of crisis. For example, dynastic founder King Taejo (1335–1408; reigned 1392–1398) appointed fifty-five officials who contributed to establishing the new dynasty as Gaeguk (establishing a nation) meritorious officials. Such officials were awarded portraits of themselves painted by court painters that were preserved at the court and handed down in their families. Because two devastating wars against the Japanese from 1592 to 1598 destroyed numerous original portraits, most extant portraits date to the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. Many remaining portraits of meritorious subjects in full-length hanging scrolls have the subjects in official attire sit on chairs and turn slightly right, according to custom. Half-length portraits in album formats were created as well. These formats and styles beginning in the seventeenth century became the basis for other portraits of scholars and officials in the following years of the Joseon dynasty.

PORTRAITS OF BUNMU MERITORIOUS OFFICIALS

The draft portraits in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco have an intriguing history, pinpointing a specific historical event. In 1728, the fourth year of his reign, King Yeongjo (1694– 1776; reigned 1724–1776) faced what was likely to be the most serious challenge of his tenure. In a widespread campaign, rebel troops were approaching the capital, Hanyang (today’s Seoul). In the third month of 1728, rebels led by Yi Injwa (1695–1728) finally conquered the city fortress of Cheongju, less than seventy miles from the capital.[1] The rebellion was instigated by the mysterious death of King Gyeongjong (1688–1724; reigned 1720–1724), King Yeongjo’s subsequent ascension to the throne, and the execution of officials who supported the previous king or who publicly questioned the circumstances of his death.

King Yeongjo set out to destroy the uprising and ordered Oh Myeonghang (1673–1728) to lead the campaign. Through shrewd strategies, Oh was able to capture Yi Injwa and defeat the enemies. King Yeongjo greeted Oh and other officials when they entered the capital city gate, as they held the severed heads of the principal rebels and delivered Yi Injwa in a carriage.

The successful suppression of the rebellion fortified and stabilized King Yeongjo’s regime, which lasted fifty-two years. For King Yeongjo, it was essential to acknowledge the officials who participated in defeating the rebellion. In the fourth month of 1728, after the uprising was subdued, King Yeongjo appointed fifteen of these men as meritorious officials, grouping them into three ranks based on their achievements and titles. The only first-rank official was Oh Myeonghang, the primary leader in suppressing the rebellion. Pak Munsu (1691–1756), Pak Chansin (1679–1755), Lee Sam (1677–1735),[2] Cho Munmyeong (1680–1732), Pak Pilgeon (1671–1738), Yi Manyu (1684–1750), and Kim Jungman (1676–1755) were appointed to the second rank. Third-rank officials were Yi Suryang (1673–1735), Yi Ikpil (1674–1751), Kim Hyeop (dates unknown), Cho Hyeonmyeong (1690–1752), Gwon Hihak (1672–1742), Yi Bohyeok (1684–1762), and Pak Donghyeong (1695–1739). For the group title, King Yeongjo determined a phrase with ten characters but shortened it to Bunmu (renowned military).[3] Upon the king’s order, the Bureau for Recording Meritorious Deeds and Awards (Nokhundogam) was created.

The Bureau recorded every detail of the preparation, process, and execution in appointing Bunmu meritorious officials along with all the king’s words and orders. This record book, Bunmu nokhundogam uigwe (Royal protocol of appointing Bunmu meritorious officials), documents the ceremonies and rewards as well as materials and resources used for both.[4] According to the royal protocol, rewards to the officials were numerous and varied by rank. For example, King Yeongjo awarded the first-rank official, Oh Myeonghang, ten personal guards, thirteen slaves, seven soldiers, one hundred fifty land units, fifty ryang of silver, one large roll of silk fabrics, and one horse. In addition, Oh’s social rank, along with those of his direct family members, was raised three ranks.[5] Other rewards were prepared for ceremonies for the appointed fifteen officials. After the blood oath of loyalty on the eighteenth day of the seventh month in 1728, King Yeongjo hosted a banquet where he bestowed royal decrees, his calligraphy, and individual portraits to each official. The royal protocol elaborately describes the preparations, including how many resources were used for the king’s gifts such as the portraits.

Nine painters were summoned to paint the portraits of fiften meritorious officials.[6] The leader of the painters’ group was Jin Jaehae (1691–1769), who painted the portrait of King Sukjong (1661–1720; reigned 1674–1720) and who also participated in oppressing the rebellion in 1728. The other eight painters were also named as court painters at that time, who painted several royal portraits and documented court events. Among them, Pak Dongjin, Heo Suk, and Jang Taeheung participated in the album project to celebrate King Sukjong’s entering the Bureau of Elderly Officials (Giroso) in 1719.[7] Ham Sehwi, Kim Sejung, and Yang Giseong painted King Yeongjo’s royal portrait in 1733. Jang Deukman (1684–1764) also painted several kings: King Sukjong in 1713, King Sejo (1417–1468; reigned 1455–1468) in 1735, and King Yeongjo in 1748. Kim Duryang (1696–1763), probably the youngest painter of the Bunmu portraits, was one of King Yeongjo’s favorite painters, evidenced by the fact that the king bestowed on him a pen name, Namli. The royal protocol also records the details of the process of painting screens depicting various events such as banquets and ceremonies for the meritorious officials, including the paintings’ dimensions, materials, and monetary and other resources.[8]

DRAFT PORTRAITS AT THE ASIAN ART MUSEUM OF SAN FRANCISCO

In 1992, the museum received the draft portraits of eight Bunmu meritorious officials (fig. 1) from Arthur J. McTaggart (1915–2003). McTaggart went to Korea in 1953 as a US government officer. In 1956, he was appointed as the director of the US Information Service Office in Daegu, Korea. Likely from that time on, he started to collect antiques and got to know contemporary artists, including Lee Jungseob (1916–1956), a well-known twentieth-century artist. In 1956, McTaggart donated three small but important paintings by Lee on the foil lining of cigarette packs to New York’s Museum of Modern Art.[9] After serving as the director of the US Cultural Center in Vietnam for nine years, McTaggart returned to Daegu in 1976 and spent twenty years there teaching English. He donated 486 objects, mostly ceramics, to the Daegu National Museum in 2000, and 36 objects to the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.[10] The majority of McTaggart’s donation to the Asian Art Museum consists of ceramics, but it includes other significant artworks, such as a calligraphy couplet by Kim Jeonghui (1786–1856) as well as draft portraits of Bunmu officials and of scholar Song Siyeol (1607–1689).[11]

Ink and colors on paper. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, Gift of Arthur J. McTaggart, 1992.203.a–h. |

Fig. 1A Yi Suryang (1673–1735) |

Fig. 1B Gwon Hihak (1672–1742) |

Fig. 1C Pak Pilgeon (1671–1738) |

Fig. 1D Lee Sam (1677–1735) |

Fig. 1E Yi Manyu (1684–1750) |

Fig. 1F Yi Ikpil (1674–1751) |

Fig. 1G Kim Jungman (1676–1755) |

Fig. 1H Kim Hyeop (dates unknown) |

The draft portraits of eight Bunmu meritorious officials—Yi Suryang, Gwon Hihak, Pak Pilgeon, Lee Sam, Yi Manyu, Yi Ikpil, Kim Jungman, and Kim Hyeop—were compiled in a single album, and it was not in displayable condition; the paintings were very contaminated and fragile. In 2012, with the support of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage in Korea, the album was sent to Korea for conservation treatment, and each portrait was returned to its original format as individual sheets.[12] The officials’ faces are delicately and realistically depicted, clearly conveying the sitters’ personal characteristics. For example, the realistic depictions of Yi Manyu’s stern facial expression, flaring eyes, and abundant beard suggest the personality of a strong military man (fig. 1e). The drafts even include reverse coloring (baechae), meaning portrait painters applied colors on the backs of paintings, creating portraits with greater depth and rendering. Reverse coloring, traditionally applied to important Buddhist paintings, portraits, and sometimes figure paintings in East Asia, is rarely discovered in draft paintings. Its inclusion suggests that the painters had to put extreme care even into the drafts, especially draft portraits of Bunmu officials that the king commissioned.[13]

Draft portraits of meritorious officials were created as preparation for official portraits yet are themselves works of art. In Joseon, draft portraits were mostly done on oiled paper. Due to its semitransparency, an oiled paper was efficient for testing and checking reverse coloring. Head of fine arts division and curator of Korean painting at the National Museum of Korea, Dr. Soomi Lee, categorizes the extant draft portraits into four types: drafts with only charcoal, with only ink, with ink and light coloring, and with numerous brush strokes. [14] The draft portraits of Bunmu officials at the Asian Art Museum belong to the third type, which is probably very close to the finished official portraits. Today, there are extant finished portraits of Gwon Hihak, Yi Ikpil, Lee Sam, Yi Manyu, Pak Pilgeon, and Kim Jungman; the draft portraits of these six in the museum collection correspond to the finished ones in Korean collections. A draft portrait of Oh Myeonghang has also survived in Korea. After finished portraits were created, draft portraits were often discarded, as their primary function as drafts was completed. Therefore, these nine draft portraits of the fifteen officials are very rare and extremely significant in the study of Joseon-era portraiture of officials. Moreover, draft portraits are valuable for art historians, as they visually illustrate painters’ processes and experiments.

Along with written records, comparisons between draft and finished portraits help to date the museum’s draft portraits. In Korea, there are two extant finished portraits of Kim Jungman that depict him at different ages (figs. 2 and 3). [15] The portrait of Kim as a young man (fig. 2) is very similar in size and style to the finished portrait of Oh Myeonghang created in 1728 (fig. 4). The portrait of Kim as a young man was undoubtedly made when he was appointed as a Bunmu meritorious official. However, Kim Jungman in the finished portrait (fig. 2) looks very different than he does in the draft portrait at the Asian Art Museum (fig. 1g); in the latter Kim has a rounder, more wrinkled face and a beard. The finished portrait of Kim Jungman as an older man (fig. 3), also preserved in Korea, has the same face as seen in the draft portrait. Thus the draft portrait in the museum was probably painted later than 1728. We can therefore observe that during the Joseon dynasty, when portraits were copied, painters started by creating new draft portraits, as earlier drafts were generally destroyed.

Fig. 2 Finished portrait of Kim Jungman in his late forties. |

Fig. 3 Finished portrait of Kim Jungman in his late sixties or early seventies. |

Fig. 4 Finished portrait of Oh Myeonghang created in 1728. |

Based on written records and comparisons of draft and finished portraits, the draft portraits at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco can be dated to 1751. Lee Sam’s draft portrait in the museum (fig. 1d) is evidently similar to the finished half-length portrait in the Hampyeong Lee family collection in Korea (cat. 1, fig. 1). The sizes of the two works are comparable too. Interestingly, the album with Lee Sam’s finished portrait has calligraphy by Cho Hyeonmyeong, another Bunmu meritorious official. The same text is also found in two compilations, Baekilheon yujip (The literary collection of Baekilheon [Lee Sam]) and Gwirokjip (The literary collection of Gwirok [Cho Hyeonmyeong]). In the text, Cho clearly stated that in 1751, twenty-three years after the appointment of Bunmu meritorious officials, the portraits of fifteen officials were re-created in album formats to be kept in the Bureau for the Distribution of Meritorious Officials (Chunghunbu) as well as with each family. He wrote that, among the fifteen people, only seven were alive at the time, and the portraits of five officials were newly painted, reflecting their aged appearances. (Cho’s writing also reconfirms that the draft and half-length finished portrait of Kim Jungman were created in 1751, showing his later age.) Subjects of these five portraits were Pak Munsu, Yi Bohyeok, Kim Jungman, Pak Chansin, and the author himself, Cho Hyeonmyeong. The rest of the portraits were copied from the earlier versions kept by the families.

KOREAN PORTRAITURE IN EXHIBITIONS AND BEYOND

Portraiture was highly valued in traditional Korean society. It exhibits complex ideas about people and societal values in the Joseon dynasty. The three parties—commissioners, sitters, and painters—carefully planned and executed portrait- making projects and delicately incorporated visions and beliefs of subject and patrons. Through copy and display in various rituals, ancestors’ portraits have been handed down until today. An essential element of portraiture in general, and certainly in the Joseon era, is the perpetuity of the sitter’s characteristics and his or her legacy. The processes of portrait-making can provide insights into the past, but also can be meaningful today in relation to perception and identity. For example, in the Likeness and Legacy in Korean Portraiture exhibition, Do Ho Suh (b. 1962) deals with group identity versus individuality by assembling portraits of schoolboys and girls (cat. 9). For a person without a face in the work of Young June Lew (b. 1947), a body gesture and clothing reveal the sitter’s characteristics (fig. 3 on page 42).

The study of traditional Korean portraits has a short history. With the exception of Cho Sun-mie, a pioneering scholar in the history of Korean portraiture since the 1980s, scholars and curators have paid attention to traditional portraits only in the last two decades. Recently, families have donated or lent their ancestors’ portraits to cultural institutions in Korea, contributing to more vibrant publication and exhibition projects on portraiture.[16]

Fig. 5 Exhibition installation photo of Portrait Sketches of the Joseon period, Chobon, National Museum of Korea, 2007. |

Exhibitions on Joseon-dynasty draft portraits have been rare, the first being held at the National Museum of Korea in 2007. Entitled Portrait Sketches of the Joseon Period, Chobon, the exhibition displayed thirty-five draft and finished portraits (fig. 5). Organized by the Asian Art Museum, this 2020 exhibition, Likeness and Legacy in Korean Portraiture, is the first US exhibition on Korean portraiture. Focusing on the museum’s draft portraits of Bunmu meritorious officials, the exhibition discusses four important aspects related to Joseon portraits: the process of making portraits ranging from draft portraits to finished works as well as mountings; the philosophy and social norms associated with portrait-making, including ancestor worship, Confucianism, and identities of portrait sitters; the historical significance of Bunmu officials in 1728, explaining who they are, why they are grouped together, and how King Yeongjo bestowed portraits to the officials; continuous and innovative practices of portrait-making in contemporary portrait artworks.

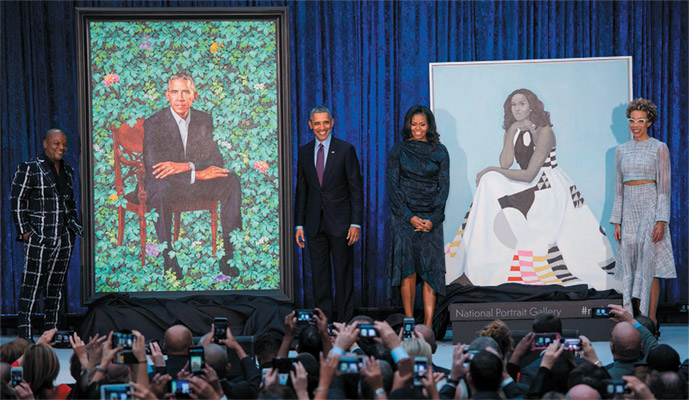

Fig. 6 Artist Kehinde Wiley, former president Barack Obama, former first lady Michelle Obama, and artist Amy Sherald at an unveiling of their portraits at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, February 12, 2018. |

Portraits transcend time and space. The impulse behind the production of portraits is universal, which is probably why, in this time of abundant selfies, portraits have been continuously produced, and people have preserved and appreciated them. During the ceremony unveiling the portraits of former President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama on February 12, 2018 (fig. 6), Kim Sajet, director of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, pointed out four primary types of people involved in making portraits: sitters, artists, patrons, and viewers.[17] This categorization is valid and applicable to the production of Joseon-dynasty portraiture almost three hundred years ago. Although in the case of the Korean portraits of Bunmu officials, both the sitters and artists had limited freedom of opinion, the characteristics and goals of portraiture that Kim Sajet addressed are still valid. The concepts of likeness, legacy, and perpetuity in portraiture can be found not only in the portraits of the former US president and first lady but also in the portraits of Bunmu officials. As the director emphasized in her remarks, viewers are the most essential to perpetuating portraits. Looking at the portraits from hundreds of years ago, we ponder whether the sitters and artists even imagined the works would be viewed by twenty-first-century audiences. At the same time, in appreciating traditional Korean portraiture, we can contemplate how we will be captured in numerous digital images of ourselves hundreds of years from now.

Footnotes:

2. Lee Sam can be romanized as Yi Sam. Upon the request of the Hampyeong Lee family representative, he is written as Lee Sam in this book.

3. In 1764, the name Bunmu was changed to Yangmu, because Bunmu was the posthumous title of Chinese Ming-dynasty emperor Yizong (1611–1644).

4. The officials in the bureau started the book project Bunmu nokhundogam uigwe [Royal protocol of appointing Bunmu meritorious officials] in 1728. This royal protocol in two volumes was made into three copies, one for the king’s own collection, and the other two to be kept in two different offices at the court. The version for the king was brought to and kept in France’s National Library in Paris until 2011 and now is in the collection of the National Museum of Korea. Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies at Seoul National University Library also owns the second volume of the royal protocol, which probably was originally in one of the two offices at the court. The king’s version is digitized.

5. Bunmu nokhundogam uigwe [Royal protocol of appointing Bunmu meritorious officials], 2.

6. Bunmu nokhundogam uigwe [Royal protocol of appointing Bunmu meritorious officials], 159.

7. Several copies of the album are extant. Three in Ewha Woman’s University Museum, the National Museum of Korea, and a private collection in Korea are registered national treasures. For the album, refer to Soomi Lee, “Official Portraits and Their Political Functions” in this book.

8. Bunmu nokhundogam uigwe [Royal protocol of appointing Bunmu meritorious officials], 437. The dimension written in the protocol is similar to the actual portrait, like that of Oh Myeonghang in the Gyeonggi Provincial Museum.

9. The images and information for the three paintings by Lee Jungseob can be found at the New York Museum of Modern Art website (www.moma.org). On the website, Lee’s name is listed as Joong Seob Lee.

10. For the information about his donation to Daegu National Museum, see Daegu National Museum, McTaggart baksa-ui Daegu sarang munhwajae sarang [The love of Daegu and Korean art by Dr. McTaggart] (Daegu, Korea: Daegu National Museum, 2001).

11. Although the donation was made in 1992, the eight draft portraits were in the museum’s study collection until 2010 and were not displayed in the Korean art galleries until 2012.

12. National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Revitalizing Korean Cultural Heritage around the World (Daejeon, Korea: National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, 2015), 66–71.

13. For an example of reverse coloring, see Cat. 1 in this book.

14. Lee Soomi, “Joseon hugi chosanghwa chobon-ui yuhyeong- gwa geu pyohyeongibeop” [Types and techniques of Joseon portrait drawings] Misulsahak [Art History] 24 (2010): 323–351.

15. Images of the two finished portraits are in Cultural Heritage Administration, Hanguk-ui chosanghwa: yeoksa sok-ui inmul-kwa jowuhada [Korean portrait painting: Encountering with people in history] (Seoul: Nulwa, 2007), 432–433. The book states that the two were in the Seoul History Museum, but they are now in the collection of the Gyeonggi Provincial Museum.

16. For instance, Gyeonggi Provincial Museum in Korea, which houses numerous important portraits, organized a special exhibition, Portraits, Painting the Eternity, in 2008. Exhibiting fifty objects, it was the first major exhibition of the subject matter. In 2011, a special exhibition at the National Museum of Korea, The Secret of the Joseon Portraits, dealt with further topics of Joseon portraiture, displaying about two hundred objects, including some twentieth-century portraits. After 2010, exhibitions focusing on specific subject matter related to Joseon portraiture became popular in Korea. For example, the King’s Portrait and Royal Portrait Hall of the Joseon Dynasty exhibition at the National Palace Museum of Korea in 2015 discussed the broader contexts of making royal portraits with about one hundred objects, including portraits, records, and materials used in the royal ceremonies. In 2018, the Kang Sehwang and Portraits of Five Generations of Kang Clan Originated in Jinju exhibition at the National Museum of Korea focused on six portraits of the same family. Most recently, in May 2019, the National Palace Museum of Korea showcased seven portraits of meritorious officials that were donated or entrusted to the museum.

17. “Obama Portrait Unveiling at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery,” February 12, 2018, YouTube video, 52:58, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uX8muQOfzqA.

The catalogue of the exhibition can be ordered at https://amzn.to/3lPlNdB

Official Portraits and Their Political Functions by Soomi Lee

Bunmu gongsin, the Last Meritorious Officials of the Joseon Dynasty by Kyungku Lee

Beyond Portraiture: New Approaches to Identity in Contemporary Korean and American Art by Robyn Asleson

Back to main exhibition | Installation images | Introduction

asianart.com | exhibitions