BUNMU GONGSIN, THE LAST MERITORIOUS OFFICIALS OF THE JOSEON DYNASTY

KYUNGKU LEEORIGINS OF MERITORIOUS TITLES

In Joseon, meritorious official (gongsin) was an honorable title given to those who made a distinguished contribution to the dynasty. Thereafter, the owners of this title were usually men who suppressed political upheaval, primarily concerning royal succession. This honor was conferred twenty-five times throughout the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910). The highest honor was paid to those who had contributed to the founding of the dynasty (Gaeguk gongsin).

The title, meritorious official (gongsin), was conferred most frequently in the fifteenth century, the first one hundred years or so after the establishment of the Joseon dynasty. The frequent ”Game of Thrones” scenarios in this period reveal the precariousness of the dynastic system. The conferment itself became rare, and the number of recipients also decreased from the sixteenth century onward, revealing that the successional process to the throne eventually stabilized.[1]

Three occasions of the meritorious title since the sixteenth century are worthy of notice: meritorious officials who assisted King Injo’s coup in 1623 (Jeongsa gongsin); those who suppressed Yi Gwal’s rebellion in 1624 (Jinmu gongsin); and those who quelled Yi Injwa’s revolt in 1728 (Bunmu gongsin). The last case is highly interesting as it was the only large-scale designation over almost a century and, furthermore, it was the last one that occurred in the Joseon dynasty. The portrait images in this exhibition, Likeness and Legacy in Korean Portraiture at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, directly relate to the 1728 revolt and its aftermath.

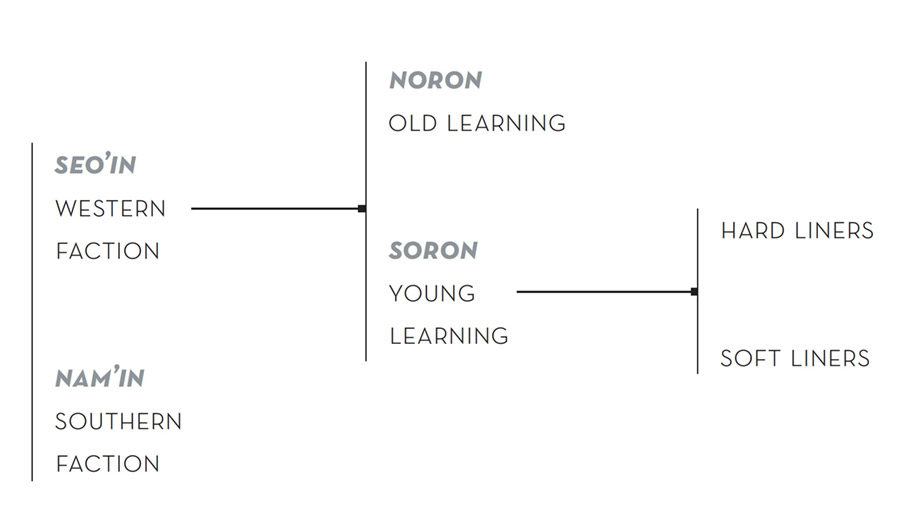

Fig. 1 Chart of political factions during the Joseon dynasty. |

Why did political upheaval happen to occur after almost a century gap? And why did it not occur again? After the King Injo coup, the royalty maintained legitimacy relatively well, but several political factions diverged on political ideas and policies. The Western and Southern factions (Seo’in and Nam’in) came into conflict, and the Southern faction was, in turn, divided into Old Learning and Young Learning (Noron and Soron). Various small factions ensued. The seventeenth century was the heyday of the so-called political factions (bungdang) (fig. 1). At first, they simply disagreed on governmental policies. Beginning with the reign of King Sukjong (1661–1720; reigned 1674–1720), the conflict escalated into questions of loyalty and treason as a central issue became succession to the throne. Fearing stigmatization as traitors, some factionalists plotted a coup.

A rebellion did occur early in the reign of King Yeongjo (1694–1776; reigned 1724–1776). Once it was suppressed, the king decided to put an end to the factional conflict once and for all. He organized a new coalition government consisting of officials from various groups, described as politics based on impartial public appointment (Tangpyeongchaek). King Jeongjo (1752–1800; reigned 1776– 1800), his successor, also adhered to this policy. The political and social system was finally stabilized during the two kings’ reigns of seventy-six years, and the Joseon dynasty enjoyed a cultural revival as well. This era saw no rebellion, therefore, no meritorious officials.

MIGHTY KING SUKJONG AND AN ILL-FATED RELATIONSHIP

Seeds of rebellion had been planted by King Sukjong, the father of King Yeongjo. As his grandfather King Hyojong (1619–1659; reigned 1649–1659) and his father King Hyeonjong (1641–1674; reigned 1659–1674) did, King Sukjong succeeded to the throne as a legitimate son. It had been exceptionally rare for a legitimate heir to come to the throne. Without a legitimate son, a son of a royal concubine or another royal relative would become a king. Coups were common. Three legitimate generations of both succession and regal continuity from King Hyojong through King Hyeonjong to King Sukjong were the only such cases in the Joseon dynasty.[2]

Fig. 2

Movie poster of Lady Jang, 1961. “Mighty King Sukjong” was politically savvy and was daring in his exercise of power. Coming of age, the king brought about several political upheavals (hwanguk) every five or ten years. Adding to the complexities and drama of this period were his love affairs and marriages, the selection of the royal successor, and issues regarding political power and governmental formation. King Sukjong’s first queen died, leaving two girls behind, and the second queen, Queen Inhyeon (1667–1701), had no child. And in the meantime, the king became enamored with a well-known and charming concubine, Lady Jang (also known as Hibin Jang; 1659–1701), who gave birth to a boy who later became King Gyeongjong (1688–1724; reigned 1720–1724). King Sukjong designated this son as his heir and her as a new queen. Queen Inhyeon was expelled as a commoner, and then retainers of the Western faction (Seo’in) who supported her were also deported, some of them even killed. This narrative might recall that of Henry VIII of England; in fact, he is often mentioned as a notable comparison to King Sukjong. Contrasts between them are pronounced, however. King Sukjong did not continue to seek a new spouse, as did Henry VIII. As time went on, King Sukjong turned his mind back to his former queen. Five years later, he brought her back as queen and simultaneously demoted Lady Jang to a concubine. Officials from the Eastern faction (Nam’in) who supported Lady Jang were immediately deported.

The whole saga finally ended in tragedy several years after their reunion. The queen died from an illness seven years after she returned. Rumor had it that her death was caused by Lady Jang’s curse, and some evidence existed to support the claim. Lady Jang’s servants were put to torture for evidence, and she was finally executed. The love-hate relationship among King Sukjong, Queen Inhyeon, and Lady Jang and the political dynamics involved provided people with an ample store of gossip and speculation. Even a satirical novel about it, titled Sassi namjeonggi (The record of Lady Sa’s southward journey), was written at the time. The melodrama has also inspired more than ten historical movies and TV a (fig. 2).

King Sukjong ruled twenty years more after the two women died. The group in power now was the Western faction that had supported Queen Inhyeon, but it soon split into two factions. The more uncompromising and severe group, committed to neo-Confucianism, was called Old Learning (Noron) and was extremely hostile toward their adversary, the Southern faction. They had been opposed to Lady Jang’s appointment and approved of her execution. Conflict with the crown prince, who later became King Gyeongjong, was inevitable. The more moderate group was called Young Learning (Soron). They adopted a more measured stance towards the opposing faction and were sympathetic to Lady Jang and her son, the crown prince.

King Sukjong initially favored Young Learning, but over time he increasingly supported Old Learning. In his later years, King Sukjong’s dissatisfaction with the crown prince grew so much that he finally formed a government mainly consisting of the members of Old Learning. It became highly likely that once enthroned the prospective king would be merely a puppet.

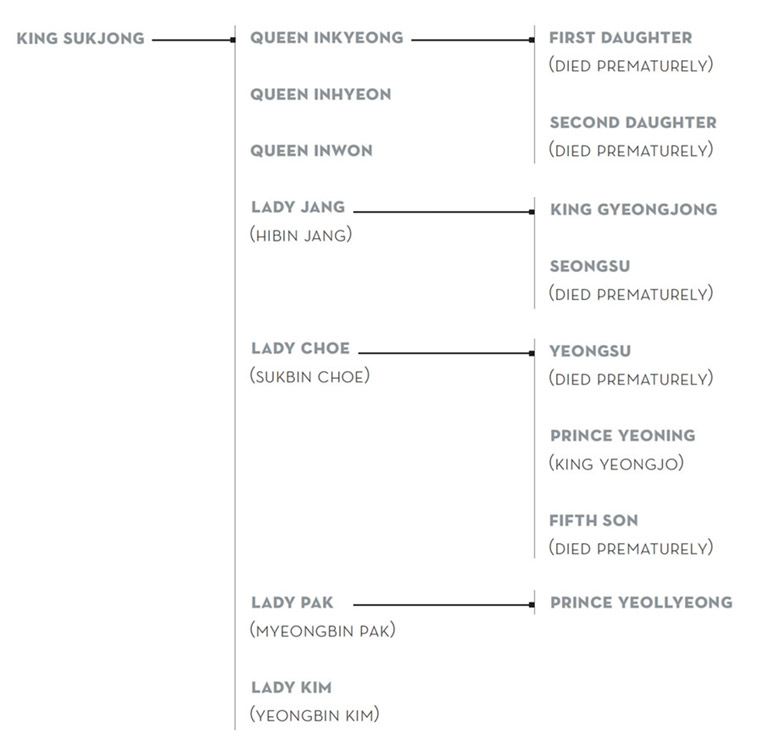

Fig. 3 Family tree of King Sukjong, King Gyeongjong, and King Yeongjo. |

In 1720, King Gyeongjong ascended the throne after King Sukjong died. Surrounded by the members of Old Learning, he did not emerge as a strong leader. The king was in poor health and had no child. The Old Learning faction aggressively lobbied to make the king’s half-brother Prince Yeoning, who was born to King Sukjong and another concubine, Lady Choe (Sukbin Choe), as the Royal Prince Successor Brother, a title given to a king’s brother who would be prospective heir to the throne. They finally succeeded and Prince Yeoning became King Yeongjo (fig. 3).

The opposing factions fought viciously in support of King Gyeongjong on the one side, and of the Royal Brother on the other. The infighting and violence took an unexpected turn with the sudden mysterious death of King Gyeongjong. Ironically enough, King Gyeongjong defended to the last his only brother, who would succeed him. In a surprise turnaround, subject to accusations about their loyalty, Old Learning was violently cast out of political power. The ascendant Young Learning further factionalized.

KING YEONGJO'S ACCESSION TO THE THRONE AND YI INJWA'S REVOLT

King Gyeongjong’s reign lasted only four years. In his mid-thirties, his death came unexpectedly. King Yeongjo came to the throne.

Long-standing factional conflicts again emerged. The Young Learning faction was uneasy because Old Learning contributed most to King Yeongjo’s accession. Young Learning hard-liners could not accept the new circumstances and spread rumors that King Yeongjo had poisoned the king. Many of the Southern faction (Nam’in) believed the rumor.

King Yeongjo executed a rigorous purge of the hard- liners early in his reign. The punishment was limited to several leading figures. Nevertheless, many continued to believe that the former king was poisoned. For them, rebellion was the only option.

In the spring of 1728, four years after the accession, a large-scale revolt took place. The government at the time consisted mainly of soft-liner officials from the Young Learning. To prove their loyalty, soft-liner officials tried to quell the hard-liners harshly. In the end, King Yeongjo organized punitive forces with Oh Myeonghang, the Minister of War, as commander and Pak Munsu as aide-de-camp.

Rebel leaders planned to rise in revolt in the southern provinces (including Chungcheong, Jeolla, and Gyeongsang provinces), and the forces from the north would enter the capital, Hanyang (today’s Seoul), under the pretense of escorting the king. Their main force was the Chuncheong province army that Yi Injwa (1695–1728) was leading. The force easily captured Cheongju Castle, the central city of Chungcheong province, and headed for Hanyang in two directions. The government forces, however, knew the rebels’ strategy and spread false information to confuse them. With a surprise attack on the rebels in Anseong and Juksan, Gyeonggi province, they won a major victory, resulting from both superior intelligence and weapons.

The rebels’ main force was destroyed, and their strategy disabled. The intended revolt in Jeolla province misfired; in Gyeongsang province, its scale was very small and put down immediately. Even in the north, leaked information led to the quick arrest of the leaders involved. The entire revolt was quelled in a month, and hundreds of people including its leader, Yi Injwa, were executed.

BUNMU GONGSIN

King Yeongjo later bestowed the title of the meritorious official (gongsin) upon those who had contributed substantially to the suppression of the revolt. The official title reads “Meritorious Officials Who Rendered Faithful Service and Showed Talent, Force, and a Feat of Arms,” usually abbreviated to Bunmu gongsin. The portraits of nine of the officials, which are displayed at the Likeness and Legacy in Korean Portraiture exhibition at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, give a glimpse into history.

The total number of meritorious officials was fifteen. The first-rank recipient was Oh Myeonghang, the commander, and the second-rank recipients included Pak Chansin, Pak Munsu, Lee Sam, Cho Munmyeong, Pak Pilgeon, Kim Jungman, and Yi Manyu. The third rank was bestowed upon Yi Suryang, Yi Ikpil, Kim Hyeop, Cho Hyeonmyeong, Yi Bohyeok, Gwon Hihak, and Pak Donghyeong. Honorable rank and position and substantial material reward were given to all of them. The entire process of deliberation and award-granting was recorded in detail in a book, Bunmu nokhundogam uigwe (Royal protocol of appointing Bunmu meritorious officials).

Substantial information about these meritorious officials survives, allowing us to understand them more fully as historical figures and human beings. Oh Myeonghang, the first-rank recipient, did not live with his honor for a long period of time. He won public confidence through the generous and swift handling of military affairs that he had demonstrated during Yi Injwa’s revolt. An anecdote reveals his good judgment. When Oh Myeonghang handled soldiers gently who committed minor errors, his aide-de- camp in contrast demanded a strict response. Oh replied magnanimously, “It is quite natural that their military discipline is relaxed now because there has been no major war like this for almost a hundred years.”[3] Although he was promoted to the second vice-premier, he died six months later. We can observe yellow eyes and a dark complexion in his portrait painted in his later years (fig. 4). These symptoms suggest that he may have died of liver cirrhosis.

Fig. 4 Detail of portrait of Oh Myeonghang. Cat. 3, fig. 1. |

Fig. 5 Portrait of Pak Munsu, 1728–1800. Ink and colors on silk. |

It is Pak Munsu who handed his name down to posterity enduringly (fig. 5). Daring and honest, he gave King Yeongjo advice and behaved irreverently without hesitation. Accordingly, he frequently faced criticism from those who were strict about observing proprieties. On one occasion, when, while red in the face with anger, he argued with King Yeongjo, the second vice-premier requested punishment for his ill-mannered behavior. Pak Munsu replied, “Ministers knelt down, but premiers just held hands and bent down in the royal symposium. Nowadays, courtiers always throw themselves flat on the ground. The relation of the sovereign and subject should be identical to that of father and child, why should not the son look the father in the face?”[5]

In most cases, King Yeongjo tolerated Pak’s unorthodox words and deeds, saying, “Though unrefined, his words are like invaluable medicine.” When he died, King Yeongjo expressed his heartfelt sorrow: “Alas, he has always been faithful to me over the last thirty-three years since I was the crown prince. We were in perfect harmony as we truly understood each other.”

Common people remembered Pak Munsu in a rather different way. While young, he had carried out his duty as a special inspector (Amhaeng’eosa) over a year. He was renowned for his impressive performance as an inspector and the uprightness, simplicity, and passionate interest in people’s welfare that he showed in his later life. The figure of “Secret Inspector (Eosa)” Pak Munsu evolved over time, with his exploits widely recounted in numerous tales. For example, he was said to solve a mysterious case with innocent people unfairly charged and to mercilessly punish the criminal and powerful in the end. “Secret Inspector” Pak Munsu has become synonymous with an investigator on the side of the people and frequently appears in contemporary dramas and animations, especially for children.

The Cho brothers—Cho Munmyeong and Cho Hyeonmyeong—wielded strong political influence. Cho Munmyeong was representative of the moderate side of the Young Learning faction. He was a teacher of King Yeongjo when he was the crown prince and became related to the king in 1727, the third year of King Yeongjo’s reign, by marriage between King Yeongjo’s son (Crown Prince Hyojang, died at 10) and Cho’s daughter. His exploits at Yi Injwa’s revolt saw him promoted through Minister of War to second vice- premier. He helped King Yeongjo push ahead with impartial political appointments (Tangpyeongchaek) to stabilize the political situation with multiple factions. He died in his early fifties in 1732 and later was consecrated in King Yeongjo’s shrine. Thus, he was honored as a meritorious official (gongsin) once again.

Cho Hyeonmyeong took over his elder brother’s position after he died. He was also a teacher of the crown prince. Cho went through various important posts with his brother. He was appointed as the second vice-premier in 1740 and later as prime minister in 1750. He was one of the officials who contributed greatly to reforming the new tax system, called Gyunyeokbeop, that King Yeongjo proclaimed. Most of the other Bunmu meritorious officials were military officials. They made a significant contribution to battles and filled important military and provincial posts after the 1728 revolt.

LEGITIMACY AND DISCONTENT

Most of the meritorious officials flourished, enjoying political power. Their legacy remains relatively intact, honoring the title of the last meritorious officials. Their portraits, which were collectively made to honor their merit, show this well.

But not all of these political and personal narratives ended well. In 1755, the thirty-first year of King Yeongjo’s reign and twenty-seven years after the 1728 revolt, members of the Young Learning faction plotted a rebellion yet again. They insisted that King Yeongjo must have poisoned the former king. King Yeongjo was shocked and ordered a strict criminal investigation. Resultingly, nearly five hundred people were killed or punished. Meritorious officials were no exception. Even Pak Munsu, King Yeongjo’s favorite, had to submit an examination report, as he was accused of being aligned with the rebellious group. He died the year following this investigation. Pak Chansin, who had once served as commander of the central army after Yi Injwa’s revolt, was beheaded and deprived of his honor due to his acquaintance with the leader of the rebellion. Accordingly, his portraits were destroyed.

All of these officials in King Yeongjo’s administration became meritorious officials (gongsin). While each had a different background, story, and characteristics, together they were grouped as one meritorious official group, as discussed in the historical analysis and this essay. The realistic portraits of the meritorious officials indeed pay homage to their individuality. While the artworks might not directly acknowledge their specific contributions, they clearly illustrate that each figure was unique, not just one of a group. Their legacies endure in the historical record, in family patrimony, in the collective imagination, in popular culture, and in powerful imagery.

Footnotes:

1. A single exception is the case of the meritorious officials designated after the Imjin War, \the Japanese invasions of Korea in 1592.

2. The early similar case was that of King Sejong, King Munjong, and King Danjong, also three succeeding legitimate generations. However, King Danjong was dethroned by a coup.

3. Yeongjo sillok [Annals of King Yeongjo], vol. 16, entry for the twenty-fourth day of the third month in 1728.

4. Lee Seongnak, Chosanghwa, geuryeojin seonbi jeongsin: pibugwa uisa, sunbi-ui eolgul-eul jindanhada [Portraits, painted spirit of scholars: Dermatologist, diagnosing scholars’ faces] (Seoul: Nulwa, 2018), 74–79.

5. Yeongjo sillok [Annals of King Yeongjo], vol. 33, entry for the twenty-fifth day of the first month in 1733.

The catalogue of the exhibition can be ordered at https://amzn.to/3lPlNdB

Sketching Legacy: Korean Portraiture at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco by Hyonjeong Kim Han

Official Portraits and Their Political Functions by Soomi Lee

Beyond Portraiture: New Approaches to Identity in Contemporary Korean and American Art by Robyn Asleson

Back to main exhibition | Installation images | Introduction

asianart.com | exhibitions