asianart.com | articles

Articles by Jean-Luc Estournel

Download the PDF version of this article

By Jean-Luc Estournel

© the author and Asianart.com

December 17, 2025

(click on the small image for full screen image with captions.)

Fig. 1

In 1970, thanks to Sherman Lee's legendary eye, the Cleveland Museum of Art was able to acquire an exceptional Tibetan painting depicting a green Tara (inv. 1970.156). (Fig.1)

Since then, this small thangka measuring 52.4 x 43.2 cm (20.5/8 x 17 in.) has continued to fascinate enthusiasts and specialists alike, as its perfection combined with atypical features resulting from a remarkable synthesis of different styles make it a unique piece within the corpus of ancient Tibetan paintings catalogued to date.

In 1977, Gilles Béguin chose it to feature in the exhibition “Dieux et démons de l'Himalaya” [1] held in Paris and Munich. The accompanying catalog was to mark a new starting point for future studies of Himalayan art. Emphasizing the synthesis of diverse elements and certain atypicalities, he exercised his legendary caution in the matter, choosing to propose a dating as an “ancient replica of a 14th century original ”. This then-new concept of “replica of an earlier original” has since been fully justified by numerous examples.

Returning to this Tara in 1981 during his annual course at the École du Louvre on “Nepalese painting and its influence”, after refining his 1977 opinion and making comparisons with miniatures from Pala manuscripts on palm leaves, he maintained his questioning while concluding that it was necessary to “recognize that we know too little about ancient paintings to make a decision”.

In 1984, Dr. Pratapaditya Pal reproduced this Tara on the cover of his book “Tibetan Paintings: A Study of Tibetan Thankas, Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries” [2]. The combination of Pala and Tibetan elements led him to consider this painting as marking the transition between what he then called the Kadampa style, referring to Pala Indian archetypes, and Sakyapa, essentially based on the Nepalese style. While raising the question of the precise geographical origin of this Tara, he came down in favor of a Tibetan and Sakyapa provenance rather than a Nepalese one, essentially because of the presence of the lion and elephant heads on the throne base, which do not exist on Newar paubhas but are frequently depicted on Tibetan paintings inspired by archetypes from northeast India.

The following years would see the emergence of numerous paintings that would refine our knowledge of the various ancient Himalayan pictorial styles.

In 1989, Susan L. and John C. Huntington published a long article in Orientations magazine in preparation for the catalog of the exhibition of the same name, “Leaves from the Bodhi Tree: The Art of Pala India (8th-12th Centuries) and its International Legacy” [3], held in Chicago in 1990.

The Cleveland Tara is reproduced on the cover and in fig. 17. She is identified as Aṣṭamahābhayatārā, “the one who protects devotees from the eight great dangers”. The two authors highlight the extraordinary rendering of miniature details that are difficult to see. After discussing the synthesis of Indian, Nepalese, and Tibetan elements, which was already widely accepted, they rely on the Tibetan consecration on the back to attribute it to the Land of Snows rather than Nepal, painted by a Newar artist or a Tibetan trained in the Nepalese tradition. Like Dr. Pal, they highlight the lion and elephant heads on the throne, adding the representation of a Tibetan monk depicted under the goddess's right hand. Again, like Dr. Pal, they attribute this thangka to the transitional "Shar mthun" tradition, referring to the style of northeastern India, dating it to the 13th century.

In 1991, Marylin M. Rhie and Robert Thurman reproduced this Tara once again in their book “Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet” [4], dating it to the late 12th or early 13th century and describing its style as "Indo-Nepalese."

In 1998, in the catalog for the exhibition "Sacred Visions: Early Paintings from Central Tibet" held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York [5], Steven M. Kossak, drawing on the strong Nepalese elements in this painting, comparisons with thangkas probably originating from Sakya, which we will discuss later, and certain murals from Shalu, concluded his essay by suggesting a possible attribution to the Newar artist Aniko, who worked on the construction of the Sakya monastery from 1260, then from 1263 at the court of the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan (1215-1294). There he held the position of "chief supervisor of all classes of craftsmen in the imperial workshop" from 1273 until his death in 1306.

In 2010, David P. Jackson, in his book "The Nepalese Legacy in Tibetan Painting" [6], once again places this Tara in the transition between the Pala and Beri styles and dates it to around 1260-1290.

Also in 2010, in his article "On recent attributions to Aniko" [7], David Weldon raised the fragility of this attribution, drawing on simple and logical elements and observations to conclude that, with its mixture of Indian and Nepalese elements, it is one of the most beautiful Tibetan paintings of the 13th century.

To date, the Cleveland Museum of Art has published a photograph of this Tara on its website with the following commentary: “Most scholars agree that this work was painted by the celebrated Nepalese artist known as Aniko”.

This attempt at attribution, typical of the Western art-historical approach, is based on three elements: the high quality of the painting, the fact that history tells us that Aniko would have been able to produce works in any known artistic style, and that stylistic elements of the Tara evoke the Shalu murals painted from 1306 onwards, i.e. after Aniko's death, by artists of Tibetan origin from the Yuan court.

Insofar as we know of no pictorial work clearly attested as being by Aniko, this attribution seems very risky. By way of comparison, if our knowledge of Italian Renaissance painting were as incomplete as our knowledge of Himalayan art, given all the masterpieces left by the great masters who would then be anonymous, wouldn't it be risky to attribute to Leonardo da Vinci a painting that was in fact by Botticelli, because although we couldn't identify the work of either of them, Leonardo would have left his name in history as a creator of genius in every speciality?

But that is pretty much the situation we find ourselves in with Cleveland's Tara, which will certainly continue to remain enigmatic for a long time to come.

The idea here is not to propose a definitive solution, but rather to try to approach it in a different way and perhaps open up new horizons for future investigations.

What most impresses any observer on first examination of this thangka is the extraordinary miniaturization of the details that cover it, in which the gaze tends to lose itself in a hypnotic way, making us forget that a painting should logically be looked at with a little distance.

When viewed as a whole, it is clear that, unlike the majority of Tibetan paintings on record, the goddess is not surrounded by secondary deities on either side of her, or in the upper corners.

An overall analysis of the composition reveals that the highly talented artist behind this work has superimposed three elements inspired by different sources. As a result, rather than a happy synthesis of Indian and Nepalese elements, it might be better to speak of a juxtaposition or interweaving of these elements, imposed by constraints linked to the commissioner's request or the particular conditions of its creation.

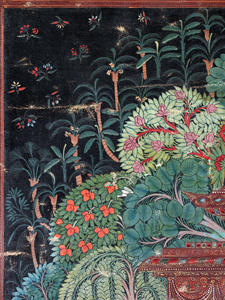

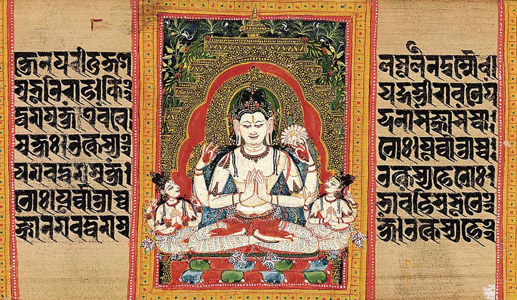

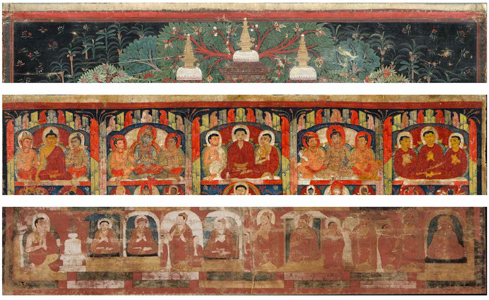

Fig. 2 The overall structure of the composition is occupied by the shrine and the vegetation against which it backs onto, which refer directly to Pala Indian palm-leaf manuscript paintings such as those illustrating a magnificent Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra preserved at the Metropolitan Museum, New-York (inv. 2001.445). (Fig.2). Even a cursory comparison makes it obvious that the artist sought to reproduce a miniature from such a manuscript by enlarging it 7 to 10 times, since the average height of vignettes painted on palm leaves oscillates between 5 and 8 centimeters.

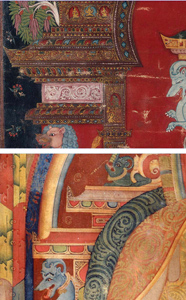

On this pictorial base, the artist has grafted a platform in the lower part, decorated with alternating heads of lions and elephants seen from the front. As this type of platform does not usually appear on miniatures of palm-leaf manuscripts, it must have been taken from a Tibetan thangka or mural known to the artist. This platform is supposed to support the lotus pedestal on which the goddess rests.

Fig. 3 It should be noted here that the lotus is not depicted supported by the platform but seems to be suspended above it. This floating perspective and the curved shape of the flower's heart undoubtedly contribute to the sense of three-dimensionality evoked by some observers.

The artist's main “tour de force” here undoubtedly lies in the extreme precision given to every detail of the sanctuary and the trees it backs onto.

The trees in the background here, depicted in greater detail than on the manuscripts miniatures due to the enlarged scale, have been described as Indian and consistent with those in the manuscripts by Susan and John Huntington [8], proof that the artist may have had access to a text listing and describing them with precision, or that he had a visual knowledge of them, which could confirm that he was indeed from the southern slopes of the Himalayas (Fig.3).

Whether the shrine is legendary or supposed to reproduce a vanished or unidentifiable monument in India, is of no importance in principle. The painter has chosen to magnify it beyond anything pictorially known to date in this typology. To achieve this, he has succeeded in synthesizing elements from the major styles found in Pala manuscript paintings.

Such a synthesis, combined with detailed and accurate representations of plants, suggests that the artist did not set out to reproduce a single miniature, but drew inspiration from several sources. This could imply that he worked in a sufficiently rich environment to have access to several manuscripts or patas of Indian origin. Another hypothesis could be that he traveled to the great Buddhist holy sites of northern India that were still active at the time and drew inspiration from what he observed there in the murals and portable paintings executed over time in the various successive Pala styles.

Fig. 4 |

Fig. 5 |

Fig. 6 |

Fig. 7 Another example of the adaptation of major Nepalese principles is that most of the building's cornices end in a curved line, unlike the classic Pala architectural style (Fig. 5). This characteristic curved line can already be seen in certain miniatures in Nepalese manuscripts dating back to at least the 11th century (Fig. 6).

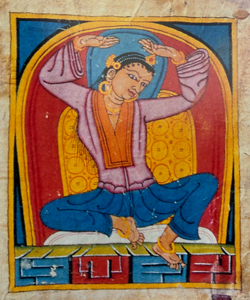

Another technical feat of miniaturization and iconographic organization, secondary deities such as the eight green Taras are reduced to a height of less than one centimeter and arranged in niches built into the walls of the sanctuary, as in the actual architecture. (Fig. 7) They do not invade the heavens and the entire background of the composition, as in most contemporary paintings. The choice of this very particular arrangement allowed the artist to follow all the iconographic precepts imposed on him while reserving the total majesty of his work for the goddess.

Both sides of the sanctuary are guarded by lions atop elephants, echoing the vyalas on elephants supporting the backrest of the goddess' throne, which evoke Indian architecture.

At the bottom of the throne composition, the platform on which the goddess's lotus pedestal is supposed to rest is just as richly decorated with plant scrolls, sometimes encircling animals, as the sanctuary itself. The classic alternation of lion and elephant heads, taken directly from the pictorial archetypes of northern India, is punctuated by caryatid columns featuring salabhanjika or yakshi, echoing those of the vedika pillars of the Shunga and Kushan periods and the struts of temples in the Kathmandu Valley. (Fig. 8) In his attempt to reproduce with virtuosity this decoration of lions and elephants, which is completely foreign to Newar art, the artist omitted to depict the drapery that usually falls in the center of the platform. (Fig. 9) Like many other details appearing in this work, the presence of this seventh animal head on the platform in place of the drapery seems unique among the corpus of ancient Tibetan paintings cataloged to date. On the other hand, it should be noted that this drapery is not always present on the steles of Pala India.

Fig. 8 |

Fig. 9 |

Fig. 10 |

Fig. 11 |

Fig. 12 |

Fig. 13 |

Fig. 14 |

Fig. 15 |

Fig. 16 |

Fig. 17 |

Fig. 18 |

Fig. 19 |

Two horizontal red bands are placed at the top and bottom of the composition, as appears on some Tibetan thangkas derived from the Pala style. (Fig. 20)

Fig. 20 |

Fig. 21 |

Even though these ancient texts may originally be associated with the Kadampa tradition, they nonetheless appear to be virtually universal and associated with all Tibetan Buddhist schools.

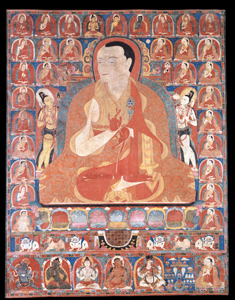

Thus, the verses of Pratimokṣa Sūtra discussing patience or forbearance as the highest austerity can be found in various ancient Kagyupa paintings, including a famous portrait of Jigten Sumgön (1143-1217) (HAR. # 19829) founder of the Drigung monastery most likely painted shortly after his death, studied by Amy Heller in her article “A Thang ka Portrait of ’Bri gung rin chen dpal, ’Jig rten gsum mgon (1143-1217)” in JIATS, no. 1 (October 2005)

The synthesis of all these details, highlighting a profound intertwining of elements evoking various sources of inspiration, leads us to reconsider the possible attribution to Aniko.

Aniko has gone down in history as a brilliant polymath who was part of a group of eighty Nepalese artists and craftsmen sent to Tibet in 1260 by King Jayabhimadeva to fulfill Phagspa's request to build a “golden roof” (gser thog) for a stupa or shrine in memory of Sakya Pandita, financed by Kublai Khan. Once the project was completed, Aniko, despite his desire to return to the Kathmandu Valley, was reportedly forced to accompany Phagspa to Kublai's court with twenty-four of his compatriots.

The attribution of the Cleveland Tara to Aniko as a Tibetan painting therefore implies that it was executed in Sakya during his stay there, in 1261-1262.

Fig. 22 Art at Sakya in ancient times is poorly documented due to successive destruction affecting the northern sanctuaries, which were the oldest in the great monastic city. However, we can safely assume that, as in all ancient Tibetan shrines that have survived to this day, the earliest phases of wall paintings and mobile sculptures must have followed, or at least been strongly inspired by, archetypes from northeastern India as in Shalu.

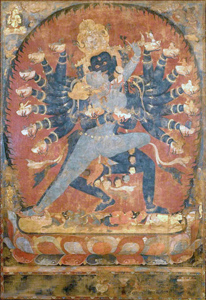

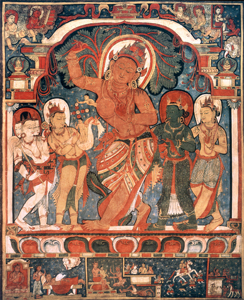

A Panjarnata Mahakala is most likely a rare and beautiful example, in the Sakyapa context, of the integration of this stylistic tradition derived from India. (Fig. 22) Its attribution to the Sakyapa tradition can be based on the subject itself, which is highly revered by this school, and especially on the spiritual lineage of the upper register. Although no figures are identified by inscriptions, the master shown facing forward in the eighth position from the left has certain details, such as white hair, that most often characterize Sachen Kunga Nyingpo (1034-1102), the third Sakya Trizin and considered the first of the five great founding masters of the Sakyapa tradition.

The few mentions of interventions by artists of Nepalese origin to adorn shrines appearing in ancient Tibetan chronicles and historical annals, written in a laconic and concise narrative style focused mainly on monastic or royal lineages, give a glimpse of their exceptional and remarkable nature from the eleventh to the thirteenth century. Among the best known are the tashi gomang for the relics of Rkyang pa chos blo de rgyang ro spe'u dmar in Samada (Khyang phu) dating from the last quarter of the eleventh century [11], and the commissions given to Nepalese artists by Jigten Gonpo: a “gilded copper parasol” to protect the Kadampa-style stupa housing the heart of Dorje Gyalpo Phagmodrupa in Densatil [12], and then, around 1200, the ornamentation of the tashi gomang he had erected in Drigung, again in homage to his master [13].

It was most likely from 1240 onwards, with the alliance between the Mongol princes and the abbots of Sakya, who were given power over Tibet, that the trickle-down effect of wealth resulting from the establishment of this patron/spiritual master relationship enabled the increasing recruitment of great artists from the Kathmandu Valley.

Fig. 23 The southern temple of Sakya, which has been partially preserved and restored, is believed to have been built starting in 1268 (after Aniko left for Kublai Khan's court) and houses a collection of important sculptures probably made by Nepalese artists in the classical style developed under the Malla dynasty, which ruled the Kathmandu Valley at the time.

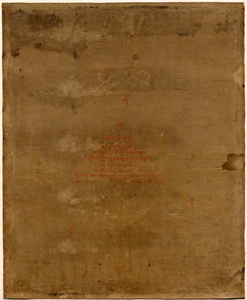

The study of the Newar contribution to Sakyapa painting in the thirteenth century is therefore based on four small thangkas, even though only one can be attributed to them with absolute certainty. (Fig. 23)

Beyond its remarkable artistic qualities, this exceptional representation of Virupa has the unique feature of bearing an inscription on the reverse indicating that it was consecrated by Sakya Pandita himself, either between 1216 (the date of his accession to the abbatial throne of Sakya) and 1244 (the year in which he left for the court of Godan, never to return to Tibet).

The style of this thangka, which is broadly similar to the best contemporary Nepalese archetypes with its characteristic succession of alternating vignettes on red and blue backgrounds and, above all, the supple and rounded treatment of the various characters and deities, which directly echoes the manuscript paintings produced in the workshops of the Kathmandu Valley, can only be the the work of a great artist who worked in Sakya between 15 and 40 years before the arrival of Aniko and his companions. Only the treatment of the multicolored vertical rocks around the central figure echoes the paintings derived from the archetypes of Pala India, where they often form a recurring motif in the backgrounds of certain compositions.

Fig. 24 |

Fig. 25 |

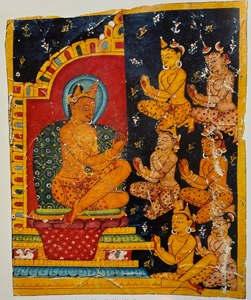

Fig. 26 |

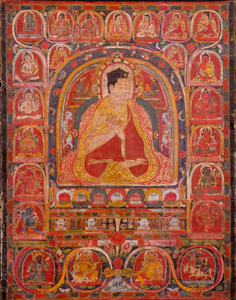

Fig. 27 A comparison of one of these three paintings with another thangka illustrating the same subject in the Indian style highlights that, apart from the general iconographic structure featuring a seated tathagata surrounded by two standing deities in the center, the two works belong artistically to two different worlds. (Fig.27) The Indian style gives the main deity and his attendants a monumental appearance, whereas in the Nepalese style example, monumentality is accorded to the throne's backrest, which seeks to reproduce the embossed copper models made by Newar craftsmen to further enhance the majesty of the seated deities in front. The second obvious difference is the contrast between the idealized stereotypes of the Indian style and the more natural curves and suppleness of the Nepalese examples, already mentioned above. The third immediately visible difference is that the borders and divisions between registers decorated with stylized lotus petals in the Indian-style models disappear in the Nepalese models, replaced by yellow lines that would remain in use for centuries to come.

It is commonly accepted that the Nepalese style developed quickly on the roof of the world with the gradual training of Tibetan painters in this pictorial tradition, but it is clear that at least during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and perhaps even a little later in some provinces far from Central Tibet, the two styles clearly evolved side by side.

Returning to the Cleveland Tara and Aniko, we have listed above several elements highlighting the distinctly Nepalese features, as well as all the archaisms and minor misunderstandings of the original Indian models incorporated into the incredible technical and aesthetic tour de force that resulted in the creation of this remarkable work.

Considering all these factors, attributing the work to Aniko raises some fundamental questions.

In 1260, following donations received from Mongol princes, primarily Kublai Khan, Phagspa asked the king of Nepal to send him a hundred Newar artists and craftsmen to work in Sakya, probably with the intention of creating works in the Nepalese style that were in vogue at the time. Sakya had become the de facto seat of power in Tibet, and like any new form of monarchy, it now needed to assert its power through artistic magnificence that was still unmatched. It should never be forgotten that art in Tibet, as elsewhere, has often been a political weapon.

Coming directly from the Kathmandu Valley, the painters who arrived in Sakya with Aniko, like all artists specializing in other techniques, were therefore required to be trained in the purest tradition of the arts under the Malla dynasty. They had to follow in the footsteps of the Virupa and the three tathagatas and be commissioned to do what they did best, rather than attempting to draw inspiration from or adapt older Indo-Tibetan styles.

Fig. 28 Furthermore, given that Aniko would have remained in Sakya supervising the work for only about two years before leaving for Kublai Khan's court, and considering the time required to complete a thangka as detailed as this Tara (several weeks or even months), it is difficult to imagine that he would have devoted such a large part of his stay there to the execution of a work that included so many archaisms and influences from a style that was foreign to his initial training.

Other details raise questions: why would Aniko have painted the monk in pure Indian style, and above all, why would he have left the red background behind the goddess completely plain, as in Indian-style paintings, instead of filling it with the classic scrollwork in variations of the same color so popular with all Nepalese artists? (Fig.28)

If we consider rejecting the attribution to Aniko due to the accumulation of numerous archaisms by the artist who painted this Tara, perhaps we should reverse our thinking and try to find its origin not in Nepalese elements, but in thangkas painted in a style derived from Pala India.

If, within the corpus of Tibetan paintings in the Indian style, we try to consider those that seem closest to the originals and are sometimes even thought to have been imported from India or at least painted in Tibet by Indian artists, we cannot ignore two aspects of the goddess Tara linked to Atisha and his disciples and to the Kadampa monastery of Reting (rwa sgreng) in central Tibet.

The first of these two thangkas (Fig. 29), formerly in the Ford Collection and now in the Baltimore Museum, depicts the goddess seated on a blooming lotus supported by a long stem, beneath a three-lobed arch among stylized multicolored rocks, above which tropical trees emerge at the top of the composition. The work could appear to be entirely Indian if it weren't for the very likely representations of Atisha and his Tibetan disciple Dromton ('brom ston) on either side of the top of the three-lobed arch, and especially in the lower left corner, a lama performing a ritual. The latter is seated in a pose identical to that of the deities surrounding him and to that of the monk depicted under the hand of the Cleveland Tara.

Fig. 29 |

Fig. 30 |

These two thangkas can in a way be considered the ancestors of the Cleveland Tara, even if a side-by-side comparison clearly shows the indisputable contribution of a Nepalese artist, or at least one trained in the techniques of the Kathmandu Valley.

Looking beyond this simple observation, perhaps we should try to consider certain details and see where they lead us, rather than dwelling on a general impression.

According to Susan and John Huntington [14], the consecration text on the back is a form of prayer most often associated with the Kadampa school, as seen in the two thangkas from the Ford/Baltimore Museum and Reting Monastery collections mentioned above. This could be a clue, but it is not sufficient to associate the work with this school, which is considered to be the closest to Indian sources, since it originates from the teachings of the Indian master Atisha.

Fig. 31 |

Fig. 32 |

Fig. 33 |

Fig. 34 |

We mentioned above Gilles Béguin's information on the Cleveland Tara, which referred to an unusual “micaceous” surface. Such an observation can be made on some of these Kagyupa thangkas, mainly portraits of Taklung abbots, perhaps because the chance discoveries of well-preserved paintings have brought them to light. This surface treatment, probably intended to make the paintings sparkle in the flickering light of butter lamps, is often difficult to observe and photograph in high light. It can be seen in some photographs as small white dots. (Fig. 35)

Fig. 35 |

Fig. 36 |

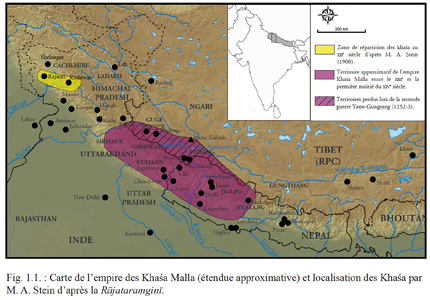

Although Western Tibet at that time was home to several kingdoms such as Guge, Purang, and Yatse, the generic location “West Tibet or West Nepal” is generally used today to identify the fluctuating territories of the “Kings of Yatse,” as named by Go Lotsawa (1392-1481) in the Blue Annals [16]. Between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, this powerful kingdom occupied parts of what are now India and Nepal, as well as other kingdoms in Western Tibet. It is more commonly known as “Khaśa Malla,” but it is now accepted that the most appropriate name is “Khaśa/Yatse Kingdom.” The eponymous capital, “Yatse,” corresponds to present-day Sinja in the Jumla district of western Nepal.

It is a fact that many paintings originating from these regions, often somewhat “provincial” in style, feature these brown borders. (Figs. 37, 38) Some even have brown bands on the sides and red bands at the top and bottom, as seen on the Cleveland Tara and a number of Kagyupa paintings. (Fig. 39)

Fig. 37 |

Fig. 38 |

Fig. 39 |

The Nepalese influence in the style of the work, combined with Indian elements and a workmanship similar to the purely contemporary Tibetan paintings mentioned above, are entirely consistent with the artist having been of Newari origin.

Fig. 40 |

In his remarkable study of the metal statuary of the Khaśa Mallas, Ian Alsop publishes a number of representations of deities that can be linked to a particular ruler and thus dated, thanks to inscriptions that are mostly not in Tibetan but in Devanagari, or both at the same time. [18]

The first is an Avalokiteshvara from the Pritzker collection (Fig. 41) in a style that he describes as clearly adapted from that of the Kathmandu Valley, but on which he notes some anomalies that make the image confusing in many details. The double inscription in archaic characters and Devanagari links it to King Ashokacalla, which allows us to date it to the third quarter of the thirteenth century. The second is a two-armed Prajnaparamita, also from the Pritzker collection (Fig. 42), which, although executed in a Newari style, follows an iconography attested in the manuscripts of Pala India, of which there are no known sculptural examples in the Kathmandu Valley. It bears a dedicatory inscription in Devanagari. The third is a representation of Prajnaparamita or Queen Dipamala (wife of King Pṛthvīmalla) kept at the Freer Gallery of Art (Fig. 43). The inscription in Tibetan and Devanagari mentions the queen's name, allowing it to be dated to the 14th century. This remarkable work is executed in a generally Nepalese style, but rests on a base directly inspired by Pala Indian archetypes.

Fig. 41 |

Fig. 42 |

Fig. 43 |

Fig. 44 |

Fig. 45 |

Fig. 46 |

Fig. 47 |

Fig. 48 |

Fig. 49 |

Fig. 50 While the statuary of the Khasa/Yatse kingdom seems to be fairly well defined today thanks to a number of inscribed pieces, the same cannot be said for the paintings. We mentioned above a few thangkas attributable to this region that combine Indian, Tibetan, and Nepalese elements, but none of them bear inscriptions that would allow for clear attribution.

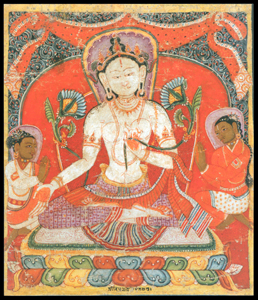

In fact, only one small painting preserved in the collection of the Tibet Museum - Alain Bordier Foundation can be indisputably associated with the Khasa/Yatse rulers. (Fig. 50) This representation of a white aspect of the goddess Tara rests at the heart of a blooming lotus surrounded by two secular figures nevertheless adorned with halos. The short Sanskrit inscription in Devanagari seems to pose minor problems of interpretation [19] but unequivocally refers to the “victorious Ripumalla,” to whom long life is wished. This ruler is known to have reigned from 1312 to 1314 and to have visited many holy places in India and the Kathmandu Valley. It is most likely him and his son Saṅgrāmamalla who are depicted praying around the goddess. It should be noted that an almost identical dedication is found on a sculpture most likely depicting Nairatma, now preserved at the Los Angeles County Museum (Inv. M.85.221). [20]

It has been suggested that this small Nepalese-style thangka may have been commissioned by the monarch during his stay in the Kathmandu Valley in 1313 [21] or from a Tibetan workshop working in the Nepalese style. [22]

It is surprising that, given that everyone accepts that the metal statues are the work of artists who may have come from the Kathmandu Valley or at least been trained by them, which would explain their very distinctive style, no one has considered that this small thangka mentioning the name of a king could be the work of a painter from the Khasa/Yatse kingdom.

Fig. 51 Indeed, without wishing to detract from this precious and beautiful painting, even though it is executed in the Newar style, it exudes a provincial form of expression that can be appreciated in the lines, the structure, and especially the traditional foliage occupying the background, which is not depicted on the cushion on which the goddess rests her back, on the red background which remains plain, and is treated in a relatively summary manner compared to the finesse of those observable on the paubhas painted at the same time in the Kathmandu Valley. (Fig. 51) It seems difficult to imagine that a wealthy monarch who placed an order with a Newar workshop would not have done so with one of the best.

It should be noted that, as with the Cleveland Tara, we are once again faced with what appears to be an enlarged miniature from a manuscript, with only one central deity surrounded by two worshippers. Another common feature between the two paintings is the large red halo with a plain background without foliage, and the cushion decorated with circles (larger on the Cleveland Tara), probably intended to represent a form of embroidery. This motif, probably floral, which does not appear to feature in contemporary Newar paubhas, is represented, almost identically to that of the Cleveland Tara, in certain miniatures in a Nepalese manuscript of the Paramartha Namasangiti on blue paper, held at the Los Angeles County Museum, which Dr. Pal dates to around 1200 [23]. (Fig. 52, 53, 54)

It is also interesting and enlightening to note that this same motif and plain red backgrounds can be found on several manuscript miniatures reproduced by Amy Heller in the chapter “Pala-influenced style: The Pala aesthetic grammar as exported to Nepal and Tibet” in her book “Hidden Treasures of the Himalayas – Tibetan manuscripts, paintings, and sculptures of Dolpo”. It is important to remember here that during the periods that interest us, Dolpo was within the sphere of influence of the kings of Yatse. (Figs. 55, 56) Her remarkable analysis even led her to note the presence on some of these miniatures of figures wearing costumes characteristic of the Tibetan-culture populations of northwestern Nepal. (Fig. 57,58)

Fig. 52 |

Fig. 53 |

Fig. 54 |

Fig. 55 |

Fig. 56 |

Fig. 57 |

Fig. 58 |

The origins and chronology of the kings of Yatse remain a subject of interpretation and minor controversy among Orientalists, but a few texts and a number of inscriptions engraved in various holy places provide a fairly clear picture of the 13th and 14th centuries, which are of interest to us here.

Fig. 59 The vast expanse of the kingdom, sometimes referred to as an empire, can be seen on the accompanying map. (Fig. 59) The legend is in French, but the empire corresponds to the purple area. The striped, purple area corresponds to the part lost during the second war against Gungthang in 1252-1253.

We mentioned above certain aspects of the Cleveland Tara that strongly evoke the artistic production known from the Kagyupa schools, notably Drigung and Taklung. It is interesting to note here that one of the first documented contacts between a Khasa/Yatse ruler and Tibetan Buddhism dates back to around 1215. [24] It is reported in the ‘bri gung ti se lo rgyus that during a trip to the shores of Lake Manasarowar to celebrate his mother's funeral rites, King Krācalla (Grags pa lde in Tibetan) met Lama Drigung Lingpa ('bris gung gling pa), nephew of Jigten Gonpo, founder of Drigung. During this meeting, the lama is said to have taught Mahāmudrā to the monarch, whom he described as Cakravartin (Universal Ruler). [25] However, Drigung Lingpa's well-documented biography suggests that this meeting could not have taken place before 1219, since after declining the offer to succeed his uncle on the abbatial throne, he remained at Drigung Monastery until the consecration of the monumental tashi gomang stupa intended to house the relics of Jigten Gonpo in 1218. It was not until 1219 that he left for Mount Kailasha in western Tibet. This is the date chosen by Roberto Vitali [26] to mark the alliance between Brigung and the kings of Yatse. It is interesting to note that Roberto Vitali dates the first pilgrimage of lamas from the Drigung and Drukpa schools to Kailash to 1191, attesting to the fact that the Kagyupa schools had already been established in the area for nearly thirty years when Drigung Lingpa arrived.

Further emphasizing the links with the Kagyupa, we know that during Dragpa Rinchen's (Grags pa rin chen) tenure on the throne of Densatil Monastery, probably around 1288-1289, a king of Yatse (probably Jītarimalla) covered the monastery's east and west stupas with gold. [27] Still about Densatil and therefore the Phagmodrupa, there are many indications that King Ashokacalla of Yatse (R. 1255-1280) was involved in the construction of at least part of the tashi gomang erected from 1267 onwards for Dragpa Tsondru (Grags pa brston 'grus), abbot of the monastery from 1235 to 1267. It is important to remember here the traditional links between Densatil and Drigung.

Fig. 60 A statuette representing Avalokiteshvara (Fig. 60) studied by Amy Heller [28] bears an inscription in Tibetan, the translation of which indicates that it was a gift from a king of Yatse to an unknown Tibetan monastery: Lha tong.

Ya tso (sic: tse) mnga’ bdag gyis bdan (sic: gdan) sa lha tong du phul ba//

“The Ya tse sovereign has offered this to the monastery of Lha tong.””

Considering that Amy Heller found two spelling mistakes when translating this short sentence, there is a strong possibility that the scribe also made a mistake in the name of the monastery. A very small correction, considering the very similar phonetics, could suggest that Lha tong is in fact Lha dong, which would make sense in the context. Indeed, the monastery of Lha dong (lha gdong dgon or pha drug lha gdong dgon) is located in Gungthang, a territory neighboring the Khasa/Yatse kingdom. In addition to its location, this small monastery belonging to the Drukpa Kagyu school, whose existence has been attested since at least the twelfth century, is strongly linked to the powerful religious figure Yanggonpa Gyeltsen Pel (yang dgon pa rgyal mtshan dpal), (1213-1258), also known as Lhadongpa Gyeltsen Pel (lha gdong pa rgyal mtshan dpal). [29] His biography mentions his close relationship with Chennga Drakpa Jungne (spyan snga grags pa 'byung gnas) (1175-1255), a disciple of Jigten Gonpo, abbot of Densatil from 1208 to 1235, then of Drigung from 1235 to 1255, where he is said to have received various donations from various Indian and Himalayan kingdoms, including that of Yatse.

Even after the decline of the Yatse Empire in the second half of the fourteenth century, the rich offerings of its rulers to Tibetan monasteries remained in history, with the fifth Dalai Lama Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, 1617-1682) reporting in his writings that the king of Yatse Ripumalla (R. 13112-1314) financed the construction of a roof for the Jowo Rinpoche chapel at the Jokhang in Lhasa (a major icon of Tibet) and that Pratāpamalla (designated as his son) and Minister Śrīkīrti offered a golden canopy to the statue itself. [30]

While the strong ties between the kings of Yatse and at least Drigung are clearly documented, a close relationship developed with the Sakyapa when the latter found themselves in a position to rule Tibet on behalf of the Mongol emperors of the new Yuan dynasty. As a powerful symbol of this new power, the Mongols and the Sakyapa proceeded to destroy the Drigung monastery in 1290.

Illustrating this radical change, King Ādityamalla, whose reign is attested in 1299 by inscription, abdicated and was sent as a simple monk to Sakya for 17 years. His son Kalyāṇamalla never ascended the throne of Yatse and became a monk at the Sakyapa monastery of Kojarnath in Purang. [31] King Puṇyamalla is remembered in history for his exchanges with Buton (Bu ston rinchen grub), abbot of Shalu. In 1339, the latter sent him a letter thanking him for a donation of gold coins. [32]

The elements originating from India observed on certain sculptures, and more specifically from northeastern India, may have their origins in the attraction of the kings of Yatse to holy sites where, as devout Buddhists, they wished to make pilgrimages, even though they ruled a clearly multi-faith empire.

Fig. 61 |

Fig. 62 |

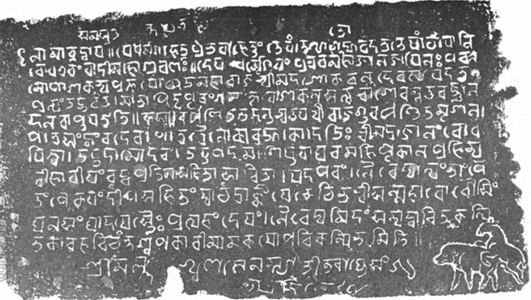

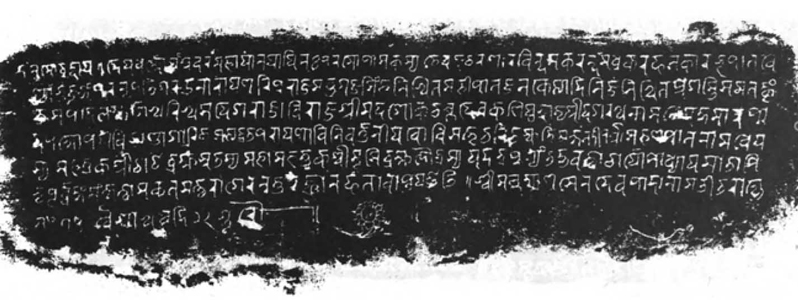

The first two, on copper plates as was common at the time, are linked to King Ashokacalla and are dated 1255 and 1278, thus attesting to at least two trips to Bihar. In both cases, he is referred to as "Khasha-Rajadhiraja," or "Emperor of the Khashas." This designation probably attests to the spiritual and political influence that this dynasty wished to exert beyond the borders of the kingdom in the holy places of Buddhism in northeastern India, which had been under Muslim rule since the successive fall of the Pala and Sena empires.

Fig. 63 These inscriptions refer to donations made by the king and his ministers, such as in 1255, the patronage of a monastery and a statue of Buddha. [33] (fig. 61 – 62)

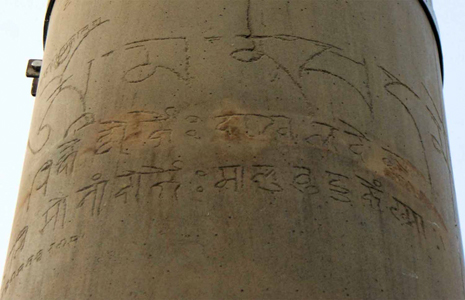

The third is associated with Ripumalla, who in 1312, together with his son, left an inscription on the pillar erected in the third century BCE by the Indian king Aśoka in Lumbini (the birthplace of the Buddha, today located in southern Nepal) (Fig. 63). The inscription "Om mani padme hum – Ripu Malla Chiran Jayatu" seems, like that on the small thangka in the Bordier collection (Fig. 50), to raise some questions of interpretation, between "wish for long victory" for Ripumalla or "wish for long life."

It is therefore likely that from these journeys to northern India, perhaps more specifically those of the thirteenth century, the monarchs (if we consider that Kracalla and Jītarimalla may also have made the pilgrimages) returned home with relics, paintings, sculptures, and manuscripts, and possibly Buddhist monks and artists fleeing the advance of the Muslims. Such a contribution to a court whose wealth is clearly attested to in history could explain the superb synthesis between Tibetan spirit, Indian iconography and archetypes, and Nepalese stylistics that characterizes Khasa/Yatse art.

Even though, considering this body of evidence, the Cleveland Tara could potentially fit perfectly into the world of Khasa/Yatse court art, in the absence of inscriptions or comparative pieces that would confirm this, it is doomed to remain an enigmatic masterpiece of Tibetan painting.

Footnotes

1. “Dieux et Démons de l’Himalaya” Paris, Editions des Musées Nationaux, 1977. Fig 99, pp 120 et 123.

2. Pratapaditya Pal “Tibetan Paintings: A Study of Tibetan Thankas, Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries” pp 44,45, plate 18.

3. Susan L. & John C. Huntington “Leaves from the Bodhi Tree: The Art of Pala lndia (8th-12th Centuries) and its International Legacy” Orientations, vol 20, October 1989

4. Marylin M. Rhie & Robert Thurman “Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet” Thames & Hudson 1991 fig. 14 p. 51.

5. Steven M. Kossak & Jane Casey Singer “Sacred Visions: Early Paintings from Central Tibet” tenue au Metropolitan Museum of Art de New York 1998 n° 37 pp 144-146 and frontispiece)

6. David P. Jackson “The Nepalese Legacy in Tibetan painting” Rubin Museum New-York 2010 pp 88-91, 97, 104, 105. fig. 5.13, 5.19, 5.38, 6.10

7. David Weldon “On recent attributions to Aniko” Asianart.com 2010 https://www.asianart.com/articles/aniko

8. Susan L. & John C. Huntington “Leaves from the Bodhi Tree: The Art of Pala lndia (8th-12th Centuries) and Its International Legacy” Dayton 1991

9. Giuseppe Tucci “Gyantse and its monasteries” part 1 & 3. Dehli: Aditya Prakashan,1989 pp 100-101 fig. 14-18

10. Susan L. et John C. Huntington : “Leaves from the Bodhi Tree: The Art of Pala lndia (8th-12th Centuries) and Its International Legacy” in Orientations, vol 20, October 1989 p. 17.

11. Translation Andrew Quintman in “Life writing as literary relic : image, inscription and consecration in tibetan biography” Yale University 2013. https://andrewquintman.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Quintman2013-MaterialReligion.pdf

12. Olaf Czaja “Medieval Rule in Tibet The Rlangs Clan and the Political and Religious History of the Ruling House of Phag mo gru pa” Austrian Academy ofSciences Press 2014 p 82

13. Olaf Czaja “Medieval Rule in Tibet The Rlangs Clan and the Political and Religious History of the Ruling House of Phag mo gru pa” Austrian Academy ofSciences Press 2014 p 379

Christian Luczanits “ Mandalas of Mandalas. The Iconography of a Stūpa of Many Auspicious Doors for Phagmodrupa” In Luczanits and Lo Bue (eds.) 2010.

14. Susan L. & John C. Huntington “Leaves from the Bodhi Tree: The Art of Pala lndia (8th-12th Centuries) and its International Legacy” Orientations, vol 20, October 1989

15. P. Pal “Himalayas- An Aesthetic Adventure” 2003 Item 101 pages 154-155

16 George N. Roerich, “The Blue Annals”. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1976 p 583

17. Laura A. Weinstein: “Nepal, : Khasa/Yatse Sculptures & Painting” https://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=1126

18. Ian Alsop: “The Metal Sculpture of the Khasa Mallas of West Nepal/ West Tibet” 2005. https://www.asianart.com/articles/khasa/index.html

19. Tibet Museum Website https://tibetmuseum.app/index.php?w=coll&cat=all&id=78

20. Ian Alsop: “The Metal Sculpture of the Khasa Mallas of West Nepal/ West Tibet” 2005. https://www.asianart.com/articles/khasa/index.html

21 Tibet Museum Website https://tibetmuseum.app/index.php?w=coll&cat=all&id=78

22. David Andolfatto. “Le Pays aux Cent-Vingt-Cinq-Mille Montagnes. Étude Archéologique du Bassin de la Karnali (Népal) entre le XIIe et le XVIe siècle”. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université Paris 4 Paris-Sorbonne, 2019. vol 1 pp. 281-282

23. P. Pal “Art of Nepal” catalogue du Los Angeles County Museum 1985 P5. Pp 199, 200

24. David Andolfatto. “Le Pays aux Cent-Vingt-Cinq-Mille Montagnes. Étude Archéologique du Bassin de la Karnali (Népal) entre le XIIe et le XVIe siècle” . Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université Paris 4 Paris-Sorbonne, 2019. vol 1 p. 275

25. Dan Martin. https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Drigung-Lingpa-Sherab-Jungne/P131

26. Roberto Vitali “Une chronologie des événements de l’histoire du Ngari Korsum (Xe-XVe siècles)” https://lecatablog.wordpress.com/2008/11/24/roberto-vitali-ngari-korsum-guge-purang/

27. George N. Roerich, “The Blue Annals”. Dehli: Motilal Banarsidass, 1976 p 583

28. Amy Heller. “A sculpture of Avalokitesvara donated by a ruler of Ya Tse (Ya rtse mnga’ bdag” In : Nepalica-Tibetica Festgabe for Chritoph Cüppers Band 1 ITTBS 2013 pp 243-245.

29. Willa Miller https://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Yanggonpa-Gyeltsen-Pel/TBRC_P5262).

30. David Andolfatto. “Le Pays aux Cent-Vingt-Cinq-Mille Montagnes. Étude Archéologique du Bassin de la Karnali (Népal) entre le XIIe et le XVIe siècle” . Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université Paris 4 Paris-Sorbonne, 2019. vol 1 p. 276

31. David Andolfatto. “Le Pays aux Cent-Vingt-Cinq-Mille Montagnes. Étude Archéologique du Bassin de la Karnali (Népal) entre le XIIe et le XVIe siècle” . Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université Paris 4 Paris-Sorbonne, 2019. vol 1 p. 60

32. David Andolfatto. “Le Pays aux Cent-Vingt-Cinq-Mille Montagnes. Étude Archéologique du Bassin de la Karnali (Népal) entre le XIIe et le XVIe siècle” . Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université Paris 4 Paris-Sorbonne, 2019. vol 1 pp. 274-275

33. David Andolfatto. “Le Pays aux Cent-Vingt-Cinq-Mille Montagnes. Étude Archéologique du Bassin de la Karnali (Népal) entre le XIIe et le XVIe siècle” . Sciences de l’Homme et Société. Université Paris 4 Paris-Sorbonne, 2019. vol 1p. 275

Articles by Jean-Luc Estournel

asianart.com | articles